1. Trevor FitzGibbon is a communication strategist who has epresented, among others, Julian Assange. Jesselyn Radack is a whistleblower lawyer and author who has represented, among others, Edward Snowden. Radack and FitzGibbon had been on apparently good terms, and Radack had publicly praised FitzGibbon’s work in August 2015:

FitzGibbon media has “a veritable Who’s Who” of leading organizations and public figures in the progressive world, Radack says: “While big PR firms may have more name cachet, FitzGibbon media makes up for it with genuine concern for client well-being, not just placing a story.”

Then, in early 2016, Radack accused FitzGibbon of raping her in November and December 2015. (FitzGibbon says they had a consensual sexual relationship, and claims that he has messages from after the alleged November incident that reflect the relationship being consensual.) Radack went to the police, but in 2017 prosecutors closed the investigation and decided not to prosecute FitzGibbon.

Radack then continued to criticize FitzGibbon, as well as “liking” and retweeting others’ posts that criticized FitzGibbon with regard to other sexual harassment accusations that had been made against him. FitzGibbon therefore sued her for libel (for more details, see this complaint). During the lawsuit, Radack continued to criticize FitzGibbon further, even though the trial court had ordered her not to use any social media “to publish or republish statements about”:

(a) the character, credibility, or reputation of Plaintiff or Defendant and/or their respective counsel;

(b) the identity of a witness or the expected testimony of Plaintiff, Defendant, or any witness;

(c) the identity or nature of evidence expected to be presented in support of any motion or at trial or the absence of such evidence;

(d) the strengths or weaknesses of the case of either party; and/or

(e) any other information the Defendant knows or reasonably should know is likely to be inadmissible as evidence in this case and that would create a substantial risk of prejudice or confusion if disclosed.

Radack was even held in contempt of court for violating the order, with the judge writing,

Radack acknowledges making the comments which [violated the order] and apologized for them claiming that they were “a desperate, emotionally charged, reflexive attempt to defend herself and respond to attacks that appeared to her to be coming from or orchestrated by the Plaintiff.” … The simple fact is that Radack deliberately violated the July 31, 2018 ORDER (ECF No. 41) by making the communications that she admittedly made. In so doing, she acted in contempt of the ORDER (ECF No. 41).

Neither contrition nor emotional distress nor illness [multiple sclerosis, apparently] nor financial difficulties [a bankruptcy] can excuse deliberate misconduct of this sort by any litigant, much less by a lawyer. And, the record here shows that Radack is a sharp-tongued, mean-spirited, proliferous user of social media. Her conduct here is just more of the same. Neither contrition nor emotional distress nor illness nor financial distress have caused Radack to ameliorate her penchant for nasty social media communication.

The original defamation case had settled, but Radack is apparently continuing to criticize FitzGibbon.

2. Here’s the complication, though: The restraining order in the earlier case would have been unconstitutional, except that Radack had stipulated to it:

Defendant concedes the motion and will not oppose entry of an order consistent with the relief sought in Plaintiff’s Motion for a Restraining Order. As counsel for plaintiff agreed at the hearing on the motion, this concession obviates the need for depositions or a hearing on the motion…. Defendant respectfully suggests that the Court enter an order consistent with that laid out on pages 1-2 of Plaintiff’s Motion for a Restraining Order [which are nearly identical to the order that was actually issued-EV].

She therefore had agreed to the speech restriction, and had it embodied in a court order—and then spoke despite it.

Radack then apparently settled the original case, and Tweeted this about the matter:

Since April 2018, I have been involved in litigation with Trevor Fitzgibbon. We have amicably resolved our differences. As part of the settlement, I retract and withdraw every allegation and statement I have ever made against Trevor Fitzgibbon.

— unR̶A̶D̶A̶C̶K̶ted (@JesselynRadack) May 3, 2019

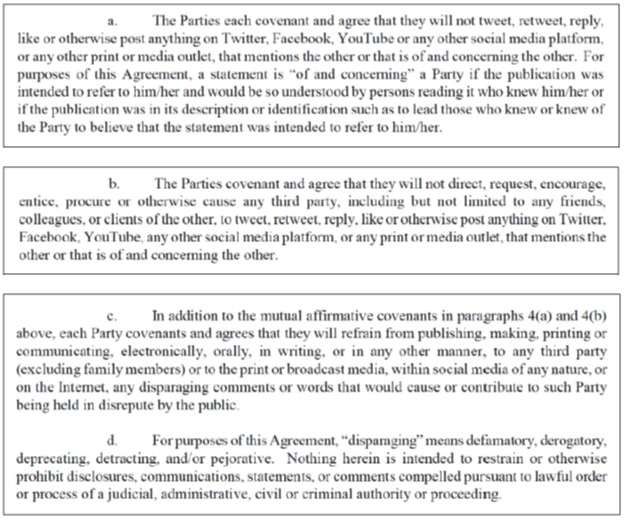

And the settlement agreement (according to FitzGibbon) stated:

Radack’s continued posts about FitzGibbon thus seem to be in violation of that settlement agreement, and Friday FitzGibbon filed suit against her again for, among other things, breach of the settlement agreement as well as defamation.

3. Radack’s consent to the speech restrictions—the restraining order in the first case, and the settlement agreement (assuming FitzGibbon’s follow-up complaint accurately reports it)—was doubtless given under pressure, stemming from the costs and risks of the continuing litigation. Nonetheless, promises not to speak are legally binding (see Cohen v. Cowles Media, Inc. (1991)), and that’s also true of promises extracted under litigation pressure.

I don’t know who’s right and who’s wrong as to the original allegations, or Radack’s later follow-ups. And certainly people generally have a First Amendment right to sharply criticize those who they believe have abused them, subject to the constraints of defamation law. But this is a good illustration that, once people promise not to exercise this right, they’re generally stuck with it (unless there’s some special legal rule that makes such promises unenforceable, and such rules are rare). And this is so even if the restrictions agreed to in the promise are very broad.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2J21wPV

via IFTTT