Authored by Chris Whelan via TheInstitutionalRiskAnalyst.com,

We caused a bit of a fuss last week on CNBC by suggesting that the Federal Open Market Committee will not cut the target for Fed funds this month. We suggested instead that the Federal Reserve Board will first end the runoff of the System Open Market Account (SOMA) and then “wait and see” about any change in the rate target.

Readers of The Institutional Risk Analyst know that we tend not to follow the crowd, especially when the data suggests that the narrative is at odds with actual market conditions. To us, any sudden and poorly considered change in policy by the Fed could create even more structural problems than we already face.

The basic problem facing the FOMC is that the combination of shrinking the Fed SOMA balance sheet, Basel III and the various other rules and regulations meant to “protect” banks has the effect of actually reducing liquidity. The quarter ended June, for example, saw a lot of liquidity exit the market as we wrote last week. With the short-term markets still clearly tightening, the FOMC is in the position of having to compensate for overly restrictive prudential regulations and the negative impact of a shrinking balance sheet.

Our colleague Ralph Delguidice at Pavillion Global Markets summarized the situation nicely in a note last week.

“The problem with repo continues to be that Basel 3 was designed to make balance sheet expensive, and the private money markets are growing increasingly illiquid as a result. In a recent post the NYFRB “Liberty Street” blog demonstrates the impact of the IOER cuts (to discourage reserves) as purely transitory; with repos and various other money market rates edging back towards—and even above—the top of the target range over and over.

Once again, we see that if efforts to push private cash into GC repo flows by lowering the IOER does not incentivize capital constrained primary dealers to keep rates in the target zone, then efforts to steepen the curve from the front with fed-funds cuts may be equally futile.

Even if they do get repo rates lower—perhaps by offering repo directly in the Standing Repo Facility (SRF), the problem will be keeping mid curve yields from falling even faster. The FX basis is driven primarily by short rate differentials, and lower LIBOR will reduce FX swap costs bringing hedged foreign buyers back into the US curve.”

Whereas in past cycles the FOMC limited “fine tuning” to the adjustment of key interest rates, since 2008 the Fed has attempted the impossible by trying to manage the entire yield curve. The foray into quantitative easing or “QE” began this quixotic adventure, putting the Fed in the position of manipulating the entire term structure of interest rates via open market operations. We actually saw somebody suggest on Twitter last week that changing the rate of interest paid on excess reserves (IOER) actually “sterilizes” the runoff of the SOMA balance sheet. Really?

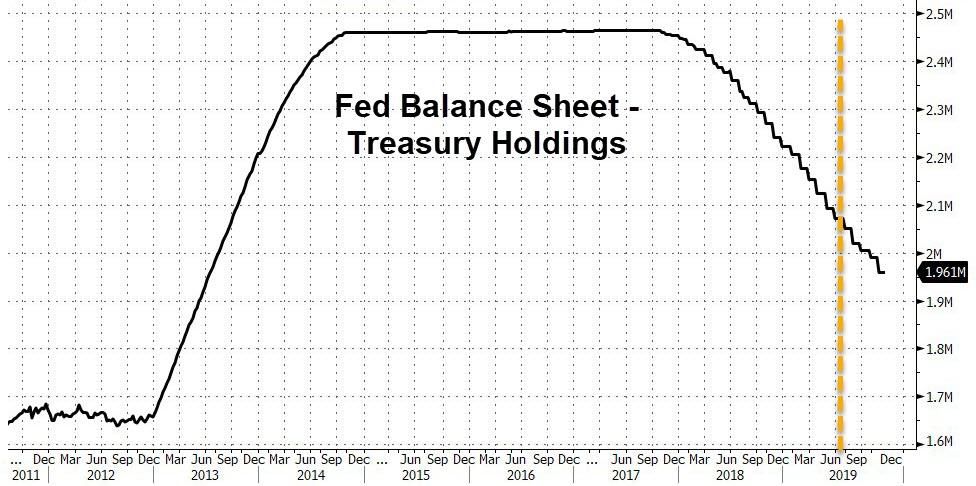

Imagine the situation if the FOMC were to actually follow the advice of the howling mob of equity analysts and captive economists, cutting the FF target while continuing to run off the Fed balance sheet. The SOMA is currently shrinking at an 8% annual rate according to our friends at Grant’s Interest Rate Observer. How far would the FOMC need to reduce the Fed funds rate to compensate for this relentless tightening of liquidity in the US banking system? Try zero.

We all are left to ponder the conflict between momentary policy, on the one hand, and prudential policy on the other. If the Fed were able to adjust Basel III and the other rules imposed upon banks since 2008 in order that they may prove their liquidity, there would be no need for an interest rate cut. Indeed, looking at the chart below from FRED showing the 10-year Treasury note and the 30-year fixed mortgage from Freddie Mac, interest rates are near the low end of the range going back five years.

If we take the upward surge in US interest rates in 2016 following the election of Donald Trump and draw a line straight across to today, we have pretty much come full circle. The difference is that since that time, the Fed has withdrawn hundreds of billions in liquidity from the system via QT, shrinking the deposit base of US banks dollar for dollar as securities owned by the Fed are redeemed by the Treasury. Both the management of the Fed’s balance sheet and the liquidity rules that apply to US banks have actually been hurting economic growth. One hand in Washington is working against the other.

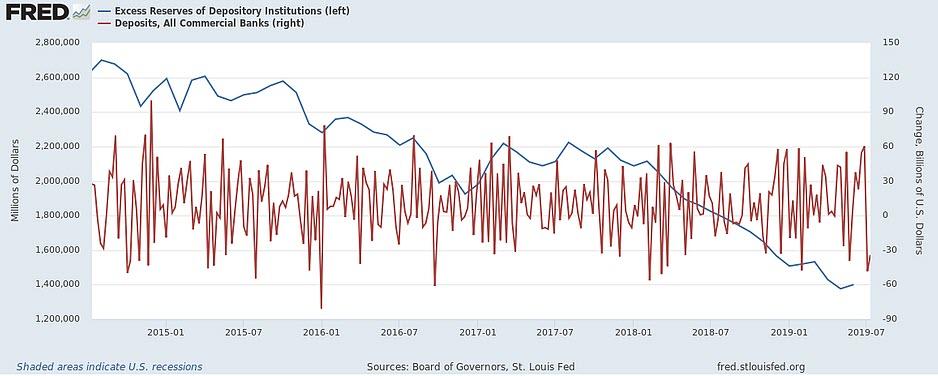

Since 2008, the FOMC has been over-compensating with monetary policy to boost the economy and fight deflation. Bank regulators, on the other hand, have been turning large banks into islands of liquidity that periodically cut off their clients to prove their ability to fund themselves in times of stress. The market breakdown seen in December 2018 illustrates this conflict in rather graphic terms. The chart above show the $1.2 trillion decline in excess reserves since 2014. Will the Fed repeat the December fiasco again this Fall?

The Fed was created a century ago to ensure a flexible currency system, yet the current conflict between monetary policy and prudential regulation of banks is a serious national problem. It’s as though we have wound back the clock to 1907, when the Treasury and J.P. Morgan & Co were the only sources of liquidity to the US financial system in times of financial crisis. Today’s toxic mix of radical money policy and retrograde prudential regulation of bank liquidity is the functional equivalent of being back on the gold standard a century ago.

Jim Grant wrote in his classic 2014 book, “The Forgotten Depression: 1921: The Crash That Cured Itself,” of the Fed’s conflict of visions.

“The Federal Reserve Act was drafted in a world of peace and limited government. It was implemented in a world of war and statism. It was as if a central bank designed to function on Earth were somehow relocated to Mars. Fixed exchange rates and free gold movement were the hallmarks of prewar monetary arrangements; the Federal Reserve had to adapt on the fly to untethered exchange rates and immobilized gold stocks.”

A century later, the US government is still struggling to get it right when it comes to providing a flexible currency to fuel the American dream. Ask not whether we should cut the target for Fed funds. Ask instead why liquidity is not moving through the US financial system in a prudent and reasonable fashion.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2Z6c1HA Tyler Durden