One could get whiplash listening to Guggenheim’s Scott Minerd’s rapidly changing opinions these days.

Back on May 29, the weightlifting CIO of the $265 billion asset manager, made a gloomy forecast on CNBC, predicting that the stock market sell-off is likely far from over, and said stocks would go “somewhere below the lows in December.” Near term, he saw an “immediate move” down to around 2,730 on the before it drops further. Oh, and he also said the next move by the Fed will be a rate hike.

Oops.

Not even two months later, everything miraculously changed, and on July 15, again on CNBC, Minerd changed his tune by 180 degrees, and no longer seeing any crash, said that he now thinks the S&P 500 could rise 15% and approach 3,500 before the end of year, comparing the current market environment to a 1998 rally amid interest rate cuts.

“This rally — whether you’re looking at bonds, you’re looking at stocks, high yield, pick whatever you want — is all being driven by liquidity. And the central banks around the world have basically signaled that they are going to step on the accelerator,” Minerd said adding that the Fed has “kind of hit the panic button” and that “you’re going to see the money flow out of the central banks into bonds, which will free up capital and that will naturally find another place to migrate to and ultimately it will end up in the hands of stocks.”

And so, Minerd now had all bases covered, with a soundbite to say he was right if stocks crashed, and another if they melted up by another 500 points. Actually, there was one base that needed covering: the same one that Trump has been pounding every single day, namely that if it all goes pear-shaped, it will be the Fed’s fault (he is actually right about that), and today, Minerd – undaunted by his recent dismal track record in making public predictions – slammed the Fed saying that the Fed should hike interest rates, not cut them.

The consequences of the Fed’s actions in the next week – the U.S. central bank is expected to cut interest rates by a quarter of a percentage point – could be with us for much longer than we think, culminating in the next recession and increasing the risk to financial stability.

In the meantime, the Fed could be delivering yet another sugar high to the economy that doesn’t address underlying structural problems created by powerful demographic forces that are constraining output and depressing prices.

Like we said, this time Minerd was correct, though we wonder: why does it take all these sophisticated financial professionals a decade to realize (or admit) what we have been saying since 2009. Must have something to do with vested year-end bonus options…

In any case, just in case everyone wasn’t completely confused yet, today’s Minerd released yet another research report in which he tried to predict not only when the next recession would hit (“we maintain our view that the recession could begin as early as the first half of 2020, but will be watching for signs that the dovish pivot by the Federal Reserve (Fed) could extend the cycle”), but also how severe it will be.

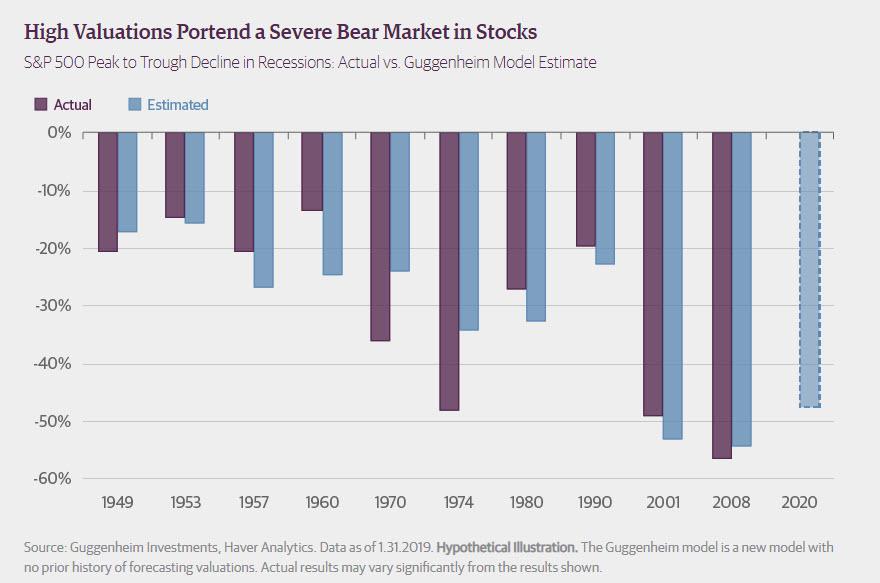

It is here that things get ugly, because as Guggenheim notes, credit markets “are likely to be hit harder than usual in the recession. This stems from the record high ratio of corporate debt to GDP and the likelihood of a massive fallen angel wave.” With that in mind, the bank notes that “when recessions hit, the magnitude of the associated bear market in stocks is driven by how high valuations were in the preceding bull market.” And given that valuations reached quite elevated levels in this cycle, Guggenheim expects “a severe bear market of 40–50 percent in the next recession.”

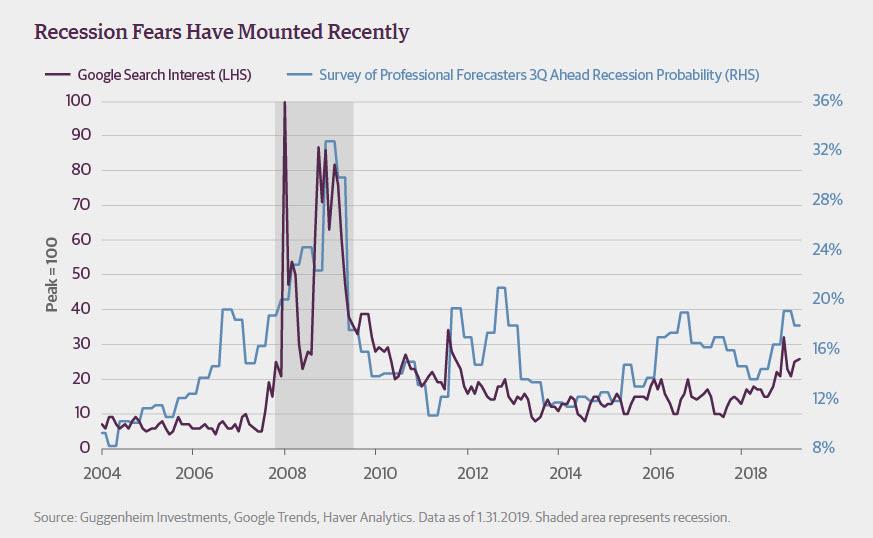

Here are some additional details, starting with Guggenheim’s framework for when the next recession will hit: here, the bank notes that its Recession Probability Model rose across all horizons in the first quarter of 2019, and while near-term the recession probability remains subdued, over the next 24 months recession probability more than doubled compared to the third quarter reading. The deterioration in leading indicators, further flattening of the yield curve, and tightening of monetary policy all contributed to rising recession risks through the first quarter. And since Guggenheim expects these trends to continue and growth to weaken in 2019, it expects recession risk to rise throughout the year.

The bank’s Recession Dashboard also continues to point to a recession starting by mid-2020. The pace of decline in the unemployment rate is beginning to slow, with the unemployment rate holding steady, on net, over the last nine months. Past Fed rate increases and balance sheet runoff mean that monetary policy may already be tight enough to induce a recession. Additionally, yield curve flattening is now back in line with the average of prior cycles, with the three-month to 10-year Treasury yield curve having inverted recently (see our previous report, The Yield Curve Doesn’t Lie, for our analysis showing that the yield curve may not be unduly flat due to quantitative easing, but rather unduly steep due to outsized Treasury issuance). The strength of the Leading Economic Index has faded, putting it in line with the range of prior cycles. Hours worked and real retail sales have also cooled, and “these trends will continue this year as fading fiscal stimulus, tighter financial conditions, and rising policy uncertainty increasingly weigh on economic activity.”

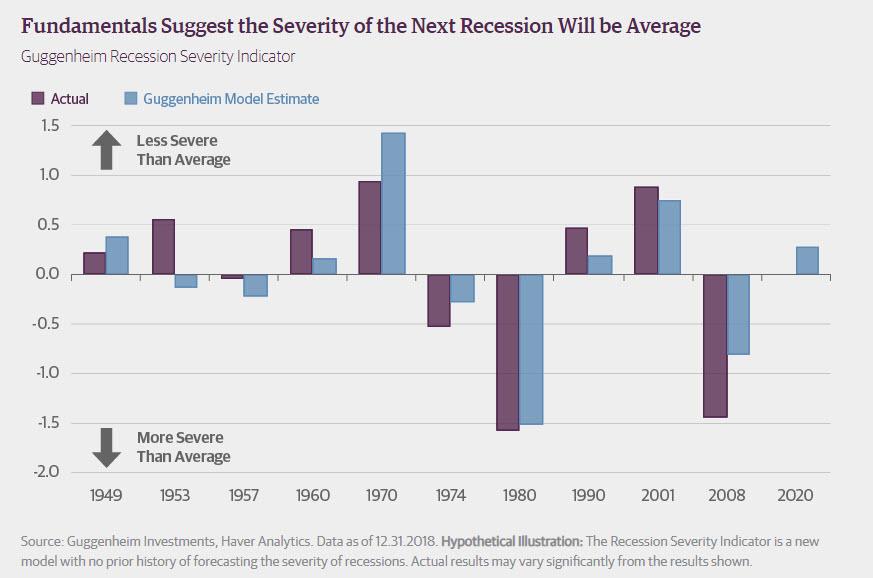

So with a recession coming as soon as under a year from now, there is some good news. First, Guggenheim notes that its work shows that the next recession will not be as severe as the last one, “but it could be more prolonged than usual because policymakers at home and abroad have limited tools to fight the downturn.”

Recession severity can be defined a number of ways: either by focusing on the i) magnitude of the contraction (the peak to trough decline in real gross domestic product (GDP)), ii) the size of the output gap (the difference between real GDP and potential output), iii) the peak unemployment rate relative to the natural rate, or iv) the length of time the recession lasts. Combining these four indicators to create a recession severity indicator that shows unsurprising results: the 2007–2009 recession was one of the worst of the post-war period, exceeded only by the “double dip” recession of 1980–1981. In contrast, the 2001 recession was mild by comparison.

Several factors play a role in determining the severity of a recession. From a sectoral basis, an overheated housing market has a strong relationship with severe recessions, reflecting the fact that housing is the largest asset for most households and is closely tied to the banking system. A related factor is stress on the banking system, which also makes recessions worse. Beyond housing, overinvestment (as measured by the private capital stock relative to GDP) contributes to more severe downturns. Other factors that can make recessions worse are monetary policy tightness (and degree of subsequent easing) and weaker global growth. Perhaps surprisingly, Guggenheim found that neither the length nor the magnitude of an expansion seem to have a relationship with the severity of the subsequent contraction. Also contrary to conventional wisdom, there is not a straightforward relationship between debt levels and recession severity, whether debt is measured by sector or from a total economy perspective. This is likely due to debt cycles lasting longer than business cycles, as the negative effects of debt accumulation can sometimes be put off in a downturn as borrowers simply take on even more debt.

Guggenheim’s analysis of these factors indicates that “the next recession should be about average. On the positive side, the housing market is not currently overheated, the banking system is sound, and the capital stock is only somewhat elevated.” In addition, Fed policymakers will likely act more quickly in response to signs of a slowdown than in the prior cycles, as evidenced by the recent Fed reaction to weaker economic data.

That’s the good news.

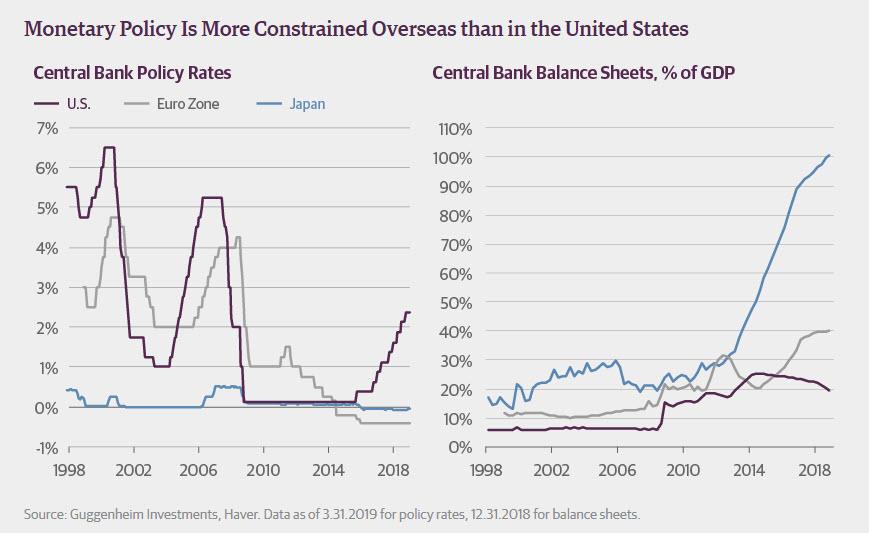

On the negative side, Guggenheim is worried about the limited scope for policy response once the recession hits. From a monetary policy perspective, Fed policymakers will be unable to ease to the same degree that they have in previous recessions, as cumulative rate cuts have averaged 5.5 percentage points in past downturns. Even with another hike or two in this cycle, per the Fed’s March 2019 Summary of Economic Projections, the Fed would have less than 3 percentage points of rate cuts available to combat the next recession.

With limited room to cut rates, it is therefore likely the Fed will again turn to unconventional policy tools, namely forward rate guidance and quantitative easing (QE). While another round of QE will undoubtedly provide some incremental stimulus, the efficacy of QE remains in question, according to Guggenheim. Furthermore, QE could also again come under fire from politicians looking to blame the Fed for economic woes, which could limit the size or duration of future QE programs. Moreover, the bank expects problems to center on corporate credit markets in the next downturn, but unlike some other central banks, the Fed lacks statutory authority to buy corporate debt or loans, at least for now. Policymakers are not likely to seek—nor would we expect Congress to pass—changes to the Federal Reserve Act that would permit the Fed to buy corporates. With these limitations in mind, the Fed is embarking on a review of its policy framework in 2019. This review will explore, among other things, the possibility of adding additional tools to the toolkit. These could include a version of Japan’s yield curve control policy and/or negative short-term rates, though both face hurdles to being deployed in the United States.

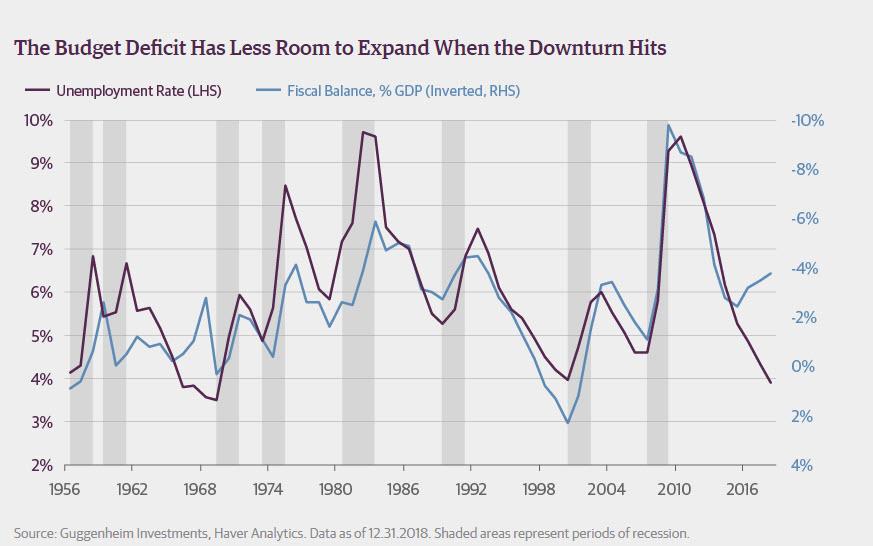

At the same time, since the monetary policy’s ability to stimulate the economy is limited, Guggenheim is also worried that fiscal policy will be constrained. Typically, the fiscal balance is countercyclical, meaning that when economic times are good we have small deficits or even surpluses that allow us to run large deficits when recessions occur, in part due to automatic stabilizers, and in part due to discretionary stimulus. However, over the past few years this relationship has reversed, with deficits widening even as the economy has strengthened due to discretionary spending increases and tax cuts.

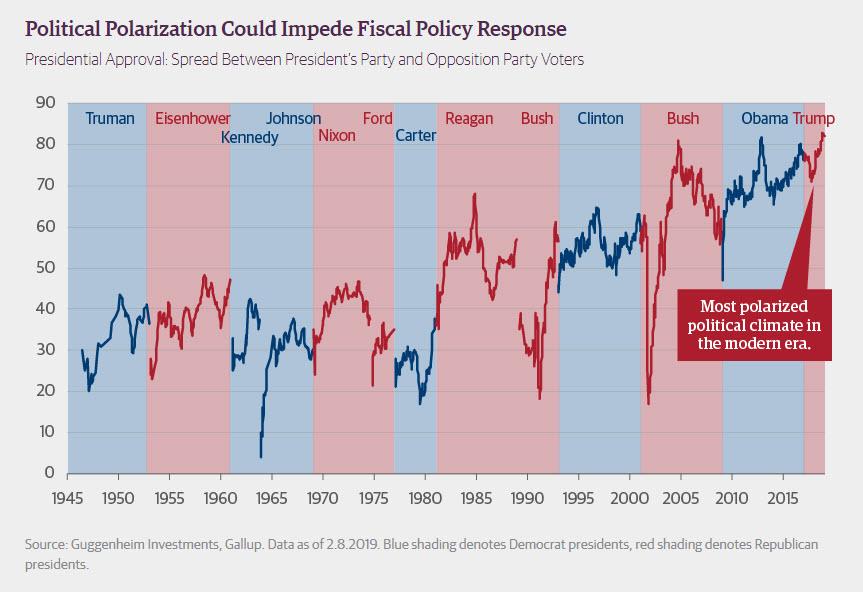

It gets worse: when the next recession finally hits, the starting point for the federal deficit will likely be much worse than it typically is at the end of an expansion, raising the prospect that fiscal hawks will resurface to raise concerns about deficits and debt. Furthermore, the expected recession interval comes at a particularly challenging time in the political calendar given the presidential election in November 2020. If growth continues to slow, will the Democrat-controlled House really want to pass a spending bill that would stimulate the economy right before the election? Guggenheim see significant obstacles to the bipartisan enactment of proactive fiscal policy measures, which is informed by our analysis of polling data that reveals a historically high degree of political polarization.

But if the US is bad, the rest of the world is far worse as policy space is even more limited overseas. As constrained as Fed policy is likely to be, the problem is much worse for the European Central Bank (ECB) and Bank of Japan (BOJ), where the starting point for inflation is lower, policy rates are still negative, and central bank balance sheets hold a much larger share of eligible assets. Given the Japanese yen’s status as a global safe-haven asset, the BOJ faces an especially difficult challenge in fending off what will likely be a deflationary exchange rate appreciation, with fiscal policy unlikely to offer much support.

Nor is fiscal policy the answer in northern Europe, where austerian ideas still hold sway. In southern Europe, fiscal tools are limited as political pressure from the north and sovereign spread widening will likely force pro-cyclical belt-tightening measures. Meanwhile, the ECB will have limited ability to cushion the downturn. If politicians in Spain, Portugal, Greece and especially Italy are not able to deliver the fiscal tightening that markets will demand, then concerns about the viability of the eurozone are likely to resurface. Advanced economies are therefore likely to be mired in a protracted downturn, spilling back into the U.S. economy by way of weak export demand, tighter financial conditions and potential concerns about exposures to weaker foreign banks.

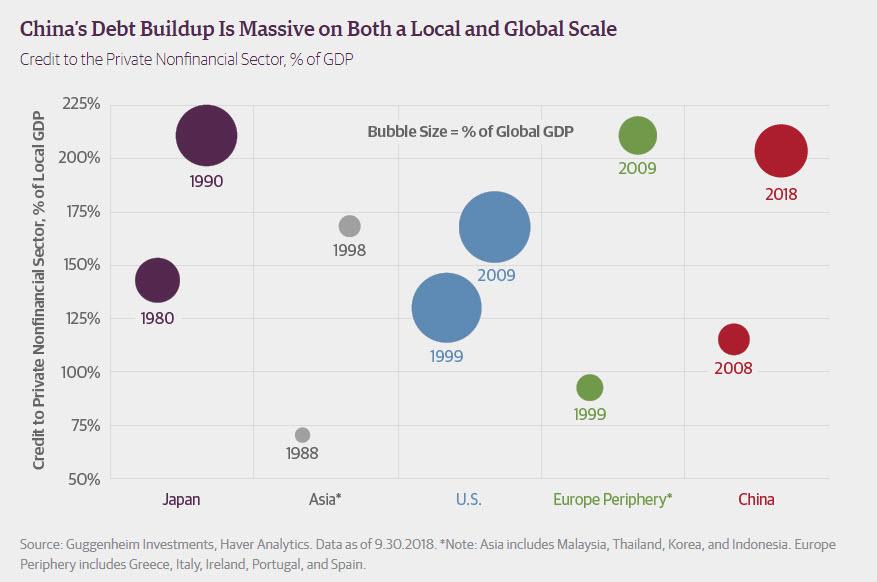

But most importantly, during the last recession a major source of global stimulus was China’s massive credit easing and infrastructure spending, without which the global recession would have been even more severe. China has, until recently, actively been working to deleverage its economy, where debt growth over the past 10 years has been on par with some of the biggest debt bubbles in history. When the global economy slows, Chinese policymakers are unlikely to deliver nearly as much stimulus as last time around, even if China manages to avoid a debt crisis or “hard landing” scenario. Other emerging markets (EM) are also unlikely to deliver the needed global stimulus, as balance of payments pressures in many EM countries will limit domestic policy space and force them to intervene in foreign exchange markets to avoid disorderly currency depreciations. This would reduce their net demand for U.S. Treasury and Agency securities, which could further complicate the Fed’s ability to deliver an appropriate degree of monetary stimulus.

Taking these factors together, Guggenheim anticipates a scenario where the magnitude of the decline in the U.S. economy is not especially severe when the recession hits, given the lack of major imbalances and relative soundness of the banking system. However, this downturn is likely to be more prolonged than usual, given the limited ability of policy to respond and the potential spillback from economic weakness abroad. The result could be a cycle that is more “U-shaped” than “V-shaped”.

Yes but…

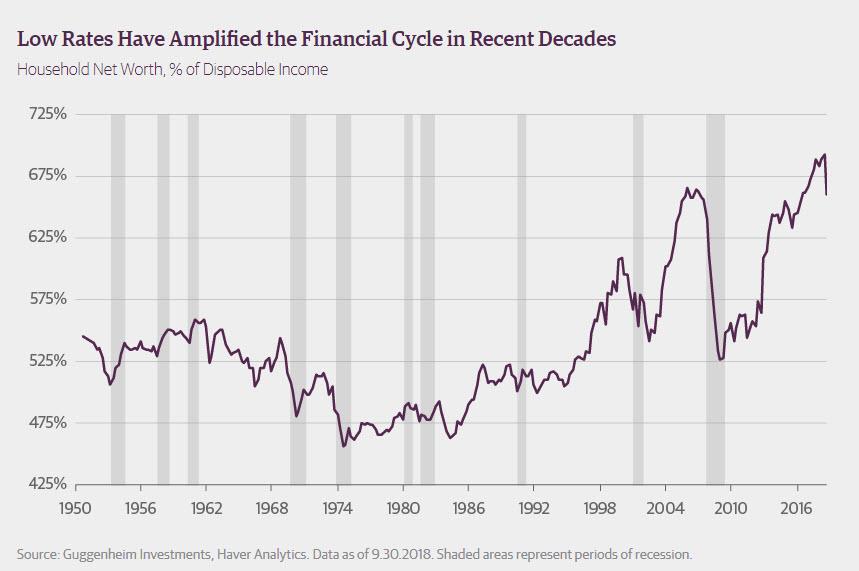

Prepare for a Steep Decline in Risk Assets: On the surface, this scenario may not seem particularly dire for investors, but Minerd would caution that market behavior is only loosely correlated with economic conditions, and a moderate recession does not mean moderate market movements. On the contrary, as he cautions “years of low interest rates have served to amplify the financial cycle over the past few decades, and this amplification has been further heightened in the current cycle by asset purchases by global central banks.”

Worse, as Minerd’s work shows, when recessions hit, the severity of the downturn has a relatively minor impact on the magnitude of the associated bear market in stocks. A far more important factor is how high valuations were in the preceding bull market. A good example is the 2001 recession, which was relatively modest economically, but saw one of the worst bear markets on record given the sky-high valuations of the tech bubble.

So given that valuations reached elevated levels in this cycle, Guggenheim’s CIO now expects a severe equity bear market of 40–50 percent in the next recession, consistent with the bank’s previous analysis that pointed to low expected returns over the next 10 years.

Finally, from a purely asset allocation standpoint, given this historical lesson and the fact that the exits tend to shrink when investors need them most, Guggenheim has been steadily upgrading portfolio credit quality and reducing spread duration in the lead up to the next recession. As Guggenheim concludes last quarter, the Fed’s dovish pivot has supported risk assets, which afforded investors a window of opportunity to further recession-proof client portfolios.

And the punchline: as Minder concludes, he will be looking to add rate duration this year given his firm’s view that policy rates will return to the zero lower bound during the upcoming recession. In other words, ZIRP is coming back, and NIRP may follow shortly after.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2LMHrQn Tyler Durden