On Friday, when CNBC’s Steve Liesman was interviewing the IMF’s new chief economist, Gita Kopinath, we suggested that he ask what the IMF’s plan is for Argentina now that the country was facing what appears yet another bond default.

Hey @steveliesman can you ask the IMF chief economist what their Argentina plan is now.

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) August 23, 2019

And while Steve did in fact ask that question, he didn’t get a direct answer for one simple reason: the IMF has no clue what it will do now that it is facing a historic loss on its latest, and biggest ever, $56 billion bailout of Argentina, which was completed less than over a year ago in September 2018.

It gets worse: not only does the IMF have to scramble to preserve its current bailout, and credibility, having sunk billions into a country which humiliated the IMF at the start of the century when it defaulted last, the monetary fund has to decide whether to keep injecting money into a nation that many believe will soon default on its foreign obligations – and the IMF – again, after President Mauricio Macri just got trounced by the populist opposition in a nationwide primary vote, after his IMF-backed program – based around much hated budget austerity and the world’s highest interest rates – failed to pull the economy out of recession. What happened next, as we reported two weeks ago, was a 20% crash in the peso and a collapse in government bonds, which pushed the implied risk of default above 80%.

It was in this dire context that IMF delegates arrived in Argentina on Saturday and, as Bloomberg reports, immediately began meetings with policy makers, facing a deja vu choice from two decades ago: risk making the turmoil even worse by withholding a $5.3 billion installment due next month – or cough it up, and risk even more losses with the IMF bailout program on the verge of collapse.

The IMF’s henchmen also have to figure out the economic plans of opposition chief Alberto Fernandez – who is set to head a less market-friendly government in a few months, an outcome which the IMF clearly not even once considered when it “offered” Macri’s regime tens of billions in loans in exchange for draconian terms that flipped public opinion against him in just a handful of months. And while elections are still two months away, and miracles can certainly happen, Macri’s 15-point primary defeat has led analysts to write him off as a lame duck.

“The IMF has put a lot in – not just money, but prestige,” said Hector Torres, a former executive director at the Fund who represented South American countries. “The fact that the arrangement is not performing well right now is an embarrassment,” he said. And the September installment is “going to be a difficult call.”

If the IMF does decide to throw good money after bad, it can justify it by pointing out what until recently, was at least modest success: Argentina was roughly on track to meet an IMF target of balancing the budget this year (excluding interest payments). Of course, the reason why the country performed as expected is also the reason why Macri is now on the way out, and the IMF’s involvement in the Argentine economy and politics has managed to unite the local population in its hatred unlike any other issue.

The Fund may cite that performance in the first half of the year as grounds for handing over next month’s payout, according to Priscila Robledo, Latin America economist at Continuum Economics in New York. “That’s what I think will be the justification: ‘Nothing happened at the end of June, we’re all fine’,” she said.

This is also known as the ostrich head in the sand approach, which works great… until Argentina “unexpectedly” announces it is defaulting once again.

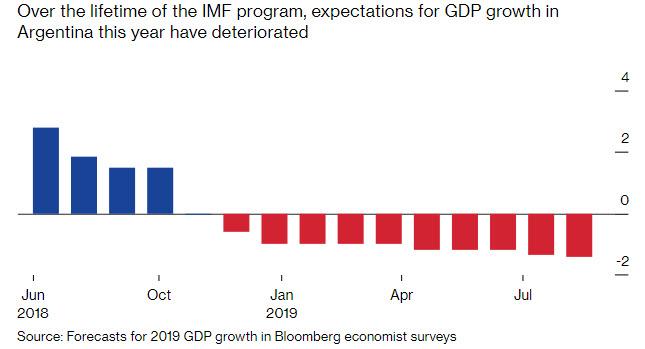

What the fund will not cite is Argentina’s economic performance, as GDP expectations have collapsed under the IMF’s supervision, as the following Bloomberg chart shows.

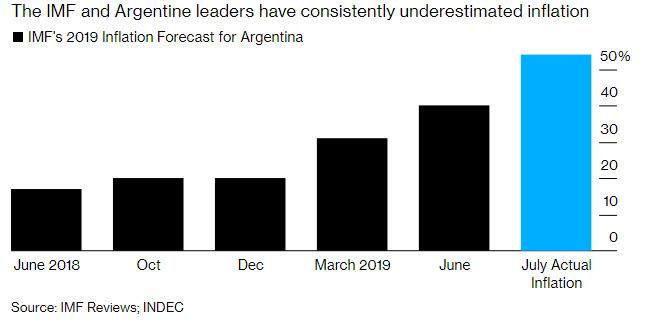

And then there are the IMF’s attempts to tame Argentina inflation. Needless to say, they have failed dismally.

Another reason why the IMFwill be careful how to spin its “success” to date is that even Macri appears to have given up on compliance. Since the ballot reverse, Macri’s government has begun to aggressively loosen policy, in contravention to IMF orders. It froze fuel prices and boosted subsidies, in an effort to shield the poorest Argentines as the peso’s latest slide threatens to push inflation even higher.

“The Fund might say its evaluation going forward is that they won’t be met,” said Daniel Marx, an Argentina “expert” who negotiated with the IMF two decades ago as the country’s finance secretary, and now heads research company Quantum Finanzas in Buenos Aires. In that case, “the disbursement could be at risk.” It would also put the IMF on the hook for billions in losses, mostly funded by US taxpayers who will be curious to learn why their money is sued to perpetuate the IMF’s gross incompetence.

The central bank could also breach IMF targets, as it burns through cash to defend the peso, Marx said. “Now that they’re starting to intervene in spot markets, that might affect net reserves.” While last week, the bank managed to steady currency and bond markets, Argentina’s benchmark debt trades below 50 cents on the dollar, a red flag for the Fund which realizes default when it sees it.

No matter how the IMF spins it, even a cursory look at Argentina’s economic performance over the past year confirms the fund’s intervention has only made the disaster worse.

As Bloomberg notes, the IMF has special criteria, which it adjusted after the Greek crisis, for jumbo loans like the one Macri got – and compliance is reassessed at each review. Two of them are key for Argentina right now: the Fund has to be satisfied that a borrower’s debt is sustainable and that it has decent prospects of access to private capital.

Judging by the markets, Argentina will almost certainly not meet those benchmarks. That opens a range of possibilities, including what the IMF calls “reprofiling” – an extension of debt maturities a la Greece, with few other changes – or the kind of restructuring brokered by the Fund for Ukraine in 2015, which involved haircuts too.

In an amusing twist Fernandez, who trumpets his experience working with the IMF as cabinet chief in the years after the 2001 crisis, insists that there’ll be no replay. “There’s no possibility that Argentina will fall into default if I’m president,” he said on Wednesday. Well, yes: one would probably not expect him to admit his first action as president will be to push the country into yet another sovereign default.

Bracing for the worst, the IMF has already opened channels to the opposition leader, including meetings with advisers Matias Kulfas and Cecilia Todesca, and those contacts are set to deepen starting this week. None of that will have any impact on the ultimate outcome, and explains why Fernandez has been vague about policy commitments and says talks with the IMF are Macri’s responsibility while he’s president. The bottom line is simple: opposition chief has said the program must be revised to allow Argentina to grow again. Failing that, a default is inevitable.

“Fernandez’s first request will be to reschedule,” said Patrick Esteruelas, head of research at EMSO Asset Management in New York. If a deal can’t be hammered out, “private sector debt holders would have to take some form of haircut.”

But while creditors will be hit, it will be the ordinary Argentina citizens that will be crushed:

Ordinary Argentines also have traumatic memories of failed IMF programs. Many blame the Fund for the epic collapse of two decades ago, one reason why Macri’s decision to go to the IMF last year was so risky.

Of course, a worst case outcome won’t be unprecedented as the Latin American nation already has an illustrious history of stuffing the IMF: in late 2001, after a series of missed budget targets and re-upped IMF loans, the government announced it was preparing to restructure debt. Argentines rushed to the banks to pull their money out, finding their deposits had been frozen by authorities, an event known as the “corralito”, an outcome similar to what happened in Greece in the summer of 2015.

A week later, the IMF finally pulled the plug, declining to disburse more funds. Mass protests erupted, leading to dozens of deaths. The political system convulsed, with four presidents succeeding each other in the space of a month. In the longer run, Argentina was frozen out of world markets for over a decade, and millions saw their savings wiped out.

While some analysts are confident that this time will be different, others argue that with an even greater build up of imbalances, the outcome could be even more devastating, especially when considering the prospect of an extended transition of power, something which traditionally results in social upheaval in Argentina.

There’ll be a four-month gap between the Aug. 11 primary and the swearing-in of a new government. And the Fund has its own leadership vacuum: Christine Lagarde, the IMF chief who signed off on Argentina’s loan, is in transit to the European Central Bank and may not be replaced for weeks.

“The IMF is in a serious pickle,” said Esteruelas. “It reminds me of the saying: If you owe the bank $100, it’s your problem. If you owe the bank $100 million, it’s the bank’s problem.”

The best news? After leaving Argentina’s economic in disaster, and the IMF’s reputation in tatters, Christine Lagarde is off to finish off her work by taking over the ECB and doing what she does best: destroying Europe once and for all.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2ZtiyeC Tyler Durden