“Panic At The Repo”: One Of The World’s Top Repo Experts Explains What Really Happened

Authored by Curvature Securities’ Scott E.D. Skyrm, one of the world’s most-respected repo market participants and experts.

Panic At The Repo

As a professional trader, I keep an eye out for the next panic or market crisis. Since the beginning of my career, there was a crash or panic every few years in one market or another. You try to think about what market is overbought. What market is in a bubble. What market just appeared on the cover of Time Magazine! Little did I ever imagine the Repo market would experience the next big panic. This is a market consisting of AAA-rated risk-free securities backed by the United States of America! How can there be a crisis in U.S. Treasury securities? We didn’t even make the cover of Time Magazine!

I write about the Repo market every day. As a service to our clients, I decided to put everything I know about the Repo market collapse down on paper. So here it is!

Modern Day Bank Run

We’ve seen the old pictures or films of people lining up outside of a bank to collect their deposits. Think of the Depression in the 1930s. Knowing that a bank can’t make good on all of their customers’ deposits means the first people to get their money are more likely to get their money. Period. Banks never keep all of their customers’ deposits as cash on hand. They invest those customers’ deposits by making loans – like a mortgage loan to a family to buy a home or loan to a business to help start a new venture. Banks invest in loans and borrow money through deposits. That also means they loan long-term and borrow short-term. Don’t worry, this is important later on.

Though banks still have the same problem today – lending long-term and borrowing short-term, increased regulation and stronger risk management has forced them to narrow the tenure mismatch. These days banks have a larger percentage of their funding borrowed in the term markets by issuing CDs, medium-term notes, and even bonds. Since banks manage their tenure mismatch much better, they are not as susceptible to the classic “run on the bank.” However, in recent years, new categories of financial institutions have popped-up that are more susceptible to “bank runs.”

Shadow Banking

The term “shadow banking” is often thrown around as the perennial risk to the financial system. There is no real definition of a “shadow bank,” but they are a key part of the Repo market and the Repo market made “shadow banking” possible. Basically, a “shadow bank” is a financial institution that performs banking functions. A “shadow bank” can be anything from a REIT (Real Estate Investment Trust), to a mortgage finance company, to a hedge fund, to a broker-dealer (like MF Global). The easiest example is a mortgage REIT. They buy mortgage-backed securities (MBS), basically mortgage loans that were packaged into securities, and borrow money to finance those securities in the Repo market. Comparing the REIT to a bank, the REIT’s “loans” are the mortgage-backed securities and the Repo transactions are the “deposits.”

Just like a bank, the REIT’s MBS portfolio might have an average weighted maturity of, say, 7 years. Their Repo transactions might be anywhere from overnight to three months. In this simple example, the REIT is lending 7 years and borrowing between overnight and three months. This maturity mismatch problem exists for “shadow banks” just like it exists for regular banks. But there is no regulation that forces “shadow banks” to mind their mismatch. As I said, this is all important later on.

Crisis of Too Few Securities

Maybe the whole Repo crisis really began several years ago. Yes! Blame it on the Financial Crisis. Just a few years ago, the Fed was in Quantitative Easing mode and buying Treasury and agency MBS securities, thus removing them from the market. At the time, I called it a back-door method to finance the budget deficit; but it worked. The combination of bond purchases and a fed funds target range of 0.0% to .25% pushed GC Repo rates close to zero. With rates set so low and the Fed still buying $50 billion of securities every month, Treasury securities were becoming scarce in the Repo market. By July 2013 QE purchases had taken so many Treasurys out of the market that the Fed was left with a SOMA portfolio of over $4 trillion. At this point, GC Repo rates were close to zero. If overnight rates turned negative, there would be tremendous stress on the Repo market, money market funds, and the Treasury market overall.

In the blink of an eye, the Fed announced the Reverse-Repurchase Program as a facility to put securities back into the market. And they rolled out this program very quickly. Announcing it in August 2013 and beginning operations in September 2013. Approved participants (not just Primary Dealers) could submit their cash to the Fed and receive Treasury securities in exchange as collateral. The perfect solution to a shortage of collateral. Cash investors, like money market funds, immediately found a new counterparty to invest their cash. They could trade with the AAA-rated Federal Reserve and receive AAArated U.S. Treasury securities. Not a bad deal! You can’t get any more risk free than that!

Pressure Building

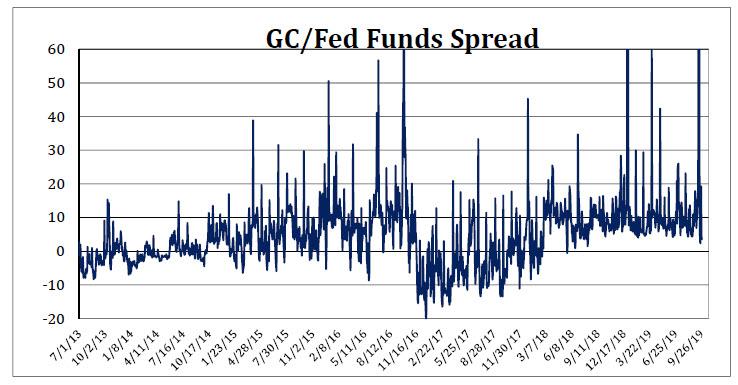

Between 2013 and the present day, a lot of things changed. The Treasury kept issuing more and more debt to fund the budget deficit, thus putting more and more Treasury securities into the market. The Federal Reserve began the QE “runoff,” where they stopped reinvesting the principal and interest of maturing SOMA portfolio securities. This put upward pressure on GC Repo rates and the spread between GC Repo and fed funds began to increase. Whereas GC Repo rates were averaging about 5 basis points below fed funds in July 2013, they now average about 10 bps above fed funds. That’s a large move!

Bank Reserves

While more and more collateral was accumulating in the Repo market, bank reserves were dwindling. Banks are required to hold a certain percentage of their liabilities in cash. This cash can be delivered to a special account at the Federal Reserve and the Fed will pay the banks an interest rate on their cash/reserves. What’s more, if banks have extra cash, they can deposit that cash at the Fed and the Fed will pay them interest on their “excess reserves.” That’s the Interest On Excess Reserves (IOER) rate. But the key point is that banks choose to leave excess reserves at the Fed. If there is a better short-term investment, they are allowed to remove that cash and invest it elsewhere.

Total bank reserve balances peaked at around $2.8 trillion in 2014 and have slowly declined since then. These days, those reserves are down to about $1.7 trillion. Yes, there’s been a significant decline, but nothing off trend in 2019, let alone no significant changes in

September 2019.

The Fed had been cut ting the IOER all year long. At the beginning of 2018, the IOER was set at the upper end of the fed funds target range. Since then, when the FOMC either raised or cut the fed funds target range, they often raised the IOER less than 25 basis points with a tightening or lowered the IOER more than 25 basis points with an ease. Since the September FOMC meeting, the fed funds target range was lowered to 1.75% to 2.00% and the IOER was set at 1.80%, or 5 basis points above the lower end of the target range. Basically, between 2018 and 2019, the Fed moved the IOER from the top of the target range to near the bottom of the range. Why?

If you’re a bank and you can invest your excess cash at the Fed at 1.80%, or with another bank in the fed funds market at 1.90%, or in Repo GC at 2.00%, which one do you choose? As the Fed moved the IOER lower and lower within the fed funds target range, it provided a greater economic incentive to get excess reserves out of Fed and into the overnight markets. No doubt moving the IOER relatively lower within the target range is one reason why bank reserves declined over the past two years.

Repo Market Participants: Cash Investors

For every Repo transaction, there is one counterparty that is a cash investor and one counterparty that is a cash borrow. The cash investor borrows the securities from their counterparty and receives securities as collateral. By far, money market funds (MMF) supply the largest amount of cash to the Repo market each day, estimated to be around $1.3 trillion. After the money funds, the bulk of the cash comes from several other kinds of investors including: insurance companies, municipalities, small banks, GSEs (like Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the federal home loan banks), broker-dealer segregated funds, and central banks. But here’s the catch – most of these cash investors need a counterparty with a rating to trade Repo. The largest money-center banks are the ones with a rating, and a rating high enough to attract the cash coming into the Repo market. Thus, bulk of customer cash coming into the Repo market each day goes to the banks.

Repo Market Participants: Cash Borrowers

Remember the discussion about the “shadow banks”? REITs, hedge funds, broker-dealers, etc.? These are the large cash borrowers. These are the leveraged entities that own securities and need the Repo market to finance their positions. Like in our example above, they own longer-term securities and loan those securities into the Repo market for three months, one month, one week, and overnight. But here is what’s important – these entities don’t have any other financing mechanism outside of the Repo market.

Repo Market Participants: Banks

The banks bring everyone together. They intermediate between the two kinds of Repo market participants – the cash investors and the cash borrowers. That’s called a Repo matched-book. The Repo desk at a bank borrows securities from a REIT or hedge fund and loans those securities to a money fund. They profit by the spread where they borrow cash and where they loan cash. Years ago, banks ran massive matched books, borrowing securities from hundreds of counterparties each day and loaning securities to hundreds of other counterparties each day. Back then, no one could compete with the big banks in the Repo market. They had all the capital and massive balance sheets.

However, that all changed after the Financial Crisis. New bank regulation from Dodd-Frank and Basel III changed the Repo market. Banks still intermediate, even though bank balance sheets are restricted by regulation. Under Dodd-Frank and Basel III, there are leverage ratios and a capital charge on Repo transactions. Regulation that never existed before. As a result, banks cut down on size of their balance sheets and reallocated assets based on revenue. Many Repo clients were the first closed because of the low Return On Assets (ROA) for Repo.

Beginning in 2015, banks were no longer sufficiently intermediating the Repo market. Liquidity issues started to appear. Banks expanded their “window dressing” on statement periods to make their balance sheets appear smaller and reduce regulatory capital charges and leverage ratios. The result was noticeably less liquidity in the Repo market on year-end, quarter-end, and sometimes month-end. At these times, if a bank Repo desk had reached its asset limit, they couldn’t book any more trades with clients. No matter what the profit was.

Market participants realized they could no longer rely on banks for Repo financing, especially on quarter-end, and they searched for new counterparties. A whole new cottage industry sprang up of “balance sheet providers.” Broker-dealers like Curvature Securities started running independent Repo matched-books. However, even with the new market participants, the Repo market still relies on banks to intermediate cash investors into the overall Repo market – like the money market funds that need a rated counterparty. On days when banks limit their balance sheets, less cash flows into the market it and causes increased volatility and rate spikes.

Market Timing

The Repo market opens at 7:00 AM EST and closes at 3:00 PM. Repo transactions generally settle for “cash” settlement; meaning the cash and securities are exchange on the same day the trade is executed. The settlement mechanism is called the “Fed Wire,” which is the electronic payments system that moves cash and securities from one counterparty to another. The Fed Wire opens at 8:30 AM.

Cash comes in the Repo market throughout the day. Some cash investors are there when the market opens, some enter the market around 8:00 AM, some around 9:00 AM, and Westcoast funds might arrive in the early afternoon. Most sellers of collateral (hedge funds, REITs, broker-dealers, etc.) – the borrowers of cash – are rushing to sell by 8:30 AM when the Fed Wire opens. Due to recent market infrastructure changes like Triparty reform and increased Daylight Overdraft (DOD) charges, most collateral sellers have a deadline to finance their positions by 8:30 AM. Many Prime Brokers require their hedge fund clients to have their trades booked by then. The key point is that the cash investors enter the market throughout the morning and even in the afternoon and the bulk of the cash borrowers need to finance their positions by 8:30 AM.

As an example, picture someone commuting into New York City each morning by car. Suppose that the George Washington Bridge charged no toll before 8:30 AM and the toll was jacked-up to $50.00 after 8:30 AM. Most people would make damn sure they crossed the bridge before 8:30 AM! It’s the same in the Repo market. Charges increase at 8:30 AM, so there is a big rush to get securities processed and delivered by then.

Cracks In The System

Cracks in the system started to appear on December 31, 2018 year-end. GC Repo rates opened at 2.93% and a panic ensued. Rates backed-up all the way to 7.25% before finally closing at 4.00% at 3:00 PM. It was a real eye opener. The Repo market had not seen such rate volatility in years. It was a shock. And, it was even more of a shock that the Fed did not intervene to pump cash into the market with rates so high on a year-end.

Over the next several months, the market continued to experience increased rate volatility and small rate spikes on January month-end, March quarter-end and June quarter-end. During this time, the Fed talked about a permanent RP Program, but nothing happened. The market was waving the white flag, but there was no response from the Fed.

Lehman Moment

That brings us to September and the collapse of the Repo market. Monday, September 16 was supposed to be a normal day. The market was expecting some funding pressure due to

- $19 billion in net new Treasury issuance (more securities in the market)

- Tax date (cash leaving the market for the Treasury)

- Money Market Fund cash decreased the previous week by about $20 billion (less cash in the Repo market)

- Bond market sell-off the previous week (generally adds collateral to the Repo market)

- A holiday in Japan (?)

All of these factors are a normal part of the Repo market. Cash comes in and out of the market. Securities come in and out of the market. The market finds a clearing price. In fact, on September 16, the Repo GC rate opened at 2.33%. The market was expecting a little funding pressure. Nothing extraordinary. In reality, there was no Lehman moment. The only thing the Repo panic has in common with Lehman are the calendar dates.

Market Panic Dynamics

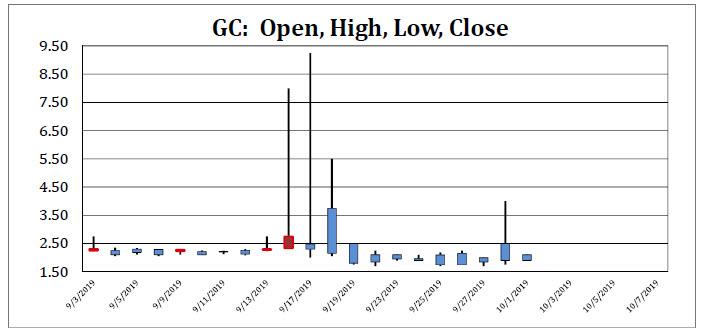

During the week of September 16, bids were thin. That is, when a bid was hit, the sellers had much more collateral to sell than the buyers (who were long cash) wanted to buy. Bids were hit and the market backed-up immediately. 3.00% traded, 3.50% traded, then 4.00%, then 4.50%, etc. The amount of securities hitting the market kept overwhelming the buyers. Everyone who was long collateral was in a rush to sell because rates were going higher. Everyone who was long cash didn’t want to buy because rates were going higher. The market peaked at 9.25%.

During the morning, as cash came into the market, rates recovered slightly. Behind the scenes it meant a cash investor had just locked-in their cash investment at a bank. The Repo trader at the bank now had actual cash to invest and they rushed to lock-in their profit. However, once that cash investment was all filled, the bids were thin again until another chunk of cash came into the market.

Look at it this way. Suppose you are a Repo trader at a large bank and your cash client calls you at 8:00 AM every day to invest their cash and set a rate. Before 8:00 AM, why lock-in a Repo rate of 3.00% at 7:30 AM when rates are gaping higher. Between 7:30 AM and 8:00 AM, there are a whole 30 more minutes for rates to keep moving higher. And 30 minutes are a long time in the Repo market at 7:30 AM! And that’s exactly what happened.

Fed Operations

On Tuesday, September 17 at 9:15 AM, during the depth of the market panic, the Fed realized they needed to inject cash into the market and announced an overnight RP operation. This was the first time the Fed used this operation in years. The operation was successful. They pumped $53.15 billion into the market and Repo GC rates closed at 2.30%; within the realm of normal. Over the next two days the Fed continued overnight operations entering the market at 8:15 AM each day and rates stabilized. On Friday, September 20, the Fed announced a schedule for overnight and term operations that went through quarterend and into October. The three term operations eventually pumped $139 billion in the market over quarter-end. On the day of quarter-end, the Fed executed a $63.5 billion overnight operation in addition to the term operations. The timing of that operation was moved up to 7:45 AM on quarter-end.

Overall, the Fed got it right. They pumped a total of $202.5 billion into the Repo market through quarter-end and progressively moved the timing of the operations from 9:15 AM to 7:45 AM. The Repo market is now functioning smoothly.

Who Won And Who Lost?

The question of who won and who lost during the Repo panic will inevitably come up. To sum it up, bank repo desks won, cash investors won, and leveraged market participants lost. Here is a closer look:

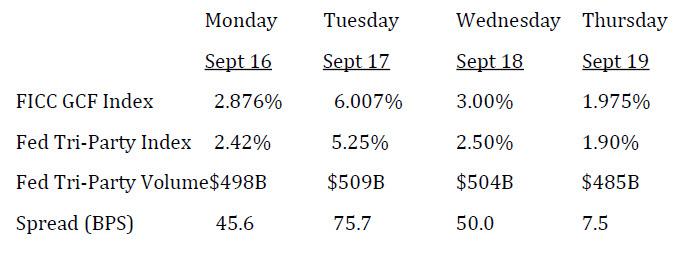

1. Bank Repo Desks – It’s pretty hard to determine exactly how much money was made or lost that week, but we can generate some rough estimates. Note: please remember there are a lot of moving parts. This is a simple estimate. If we compare the FICC GCF Index to the Fed Tri-Party Index, we can gauge, on average, where banks borrowed securities (FICC GCF) and where banks borrowed cash (Tri-Party). If we use Thursday, September 19 as a “control” date where the Street makes 7.5 basis points, we estimate that the Street normally makes about $1 million a day on Tri-Party Repo transactions. On Monday, September 16, the FICC GCF Index was 2.876% and the Tri-Party Index was 2.42% for a 45.6 basis point spread. Using the Tri-Party volume of $498 billion, means, just for Tri-Party transactions, the Street made about $6.3 million that day. The spread was even wider on Tuesday at 75.7 basis points and the profit that day was at least $10.7 million, followed by another $7 million on Wednesday. Naturally the Street marks-up clients more than the interdealer average and there is an undetermined about of deliverable GC Repo transactions, and, of course, wider spreads in the Specials market.

2. Cash Investors – Let’s say, under normal circumstances, the Tri-Party Index would be around 2.15% before the ease and at 1.90% after the ease. That means cash investors took in an additional $3.7 million in interest on Monday, $43.8 million on Tuesday, and $4.9 million on Wednesday. Thursday was a scratch. Not a bad week for cash investors! And, just like the banks, there are still a large amount of deliverable Repo GC transactions that can’t be counted.

3. Leveraged Market Participants – These are the entities that paid the price of the panic. If you add up the additional income that the banks and cash investors made, most of this came from the leveraged market participants. Based on the Tri-Party transactions, leveraged players lost, at a minimum, of $73 million that week. Once again, that figure does not include a calculation for deliverable GC Repo transactions. So … the bottom line is … I am comfortable saying that banks and cash investors earned an extra $150 million at the expense of leveraged market participants that week.

Revelations

- Bank Reserves – The decline in bank reserves didn’t cause the Repo panic, but the dwindling supply of reserves could have created a smaller cushion of extra liquidity ready to enter the Repo market. In other words, the amount of excess reserves coming out of the Fed account and into the Repo market is possibly maxed out. Perhaps the bank reserves that are rate sensitive already moved out of the Fed as the IOER rate was cut. What’s left are the reserves that are not rate sensitive and therefore a one-day Repo rate spike is not enough incentive to move that liquidity out

- Declining excess bank reserves might be the result of Repo market funding pressure and not the cause. Over the past year as Repo rates moved relatively higher and the Fed lowered the IOER, perhaps funds moved out of reserves into Repo just for that reason

- Modern Day Bank Run – The collateral sellers (shadow banks) need funding. And they need it between 7:00 AM and 8:30 AM. The panic was a classic “run on the bank.” Cash investors did not pull cash out of the market, but they made borrowing cash more expensive. The leverage market participants had no choice but to accept prevailing rates

- Price Not Credit – At no point during the Repo market panic did credit break down. The market didn’t seize up. Counterparties continued to trade. Just interest rates went higher and higher. In other words, there was never a time when there was no bid for collateral. There was always a bid. The bids just kept moving higher

- Though bank balance sheets are constrained by bank regulation, banks are still the main conduit for cash investors and the Federal Reserve to inject cash into the Repo market

- Question: Did the Fed solve the Repo funding problem by the size of the operations or the timing? Naturally, most traders assume it’s the dollar amount that eased the Repo panic. Maybe it’s the fact that the Fed plugged the timing mismatch between the collateral sellers and cash providers?

- One question that remains unanswered is what sparked the Repo panic? I still believe a block of cash left the market and has not yet returned

Recommendations

The market was spooked by the rate spike last year-end and was hoping for a structural change after every FOMC meeting this year. It all came to a head two weeks ago. Here are some things that the Fed should or should not do to fix the Repo liquidity problem:

1. RP Program

The program would be like the RRP Program, but in reverse. Instead of injecting securities into the market like the RRP Program, the RP Program would inject cash. Sounds like a good idea. A simple solution to eliminate funding spikes. However, the RP Program is a little more complicated. Such a program can come in two forms. Philosophically, is it a rate ceiling to eliminate rate spikes, like on year-end or quarter-end? Or is it a tool to better manage overnight rates, keeping them within the target range? There are pluses and minus for both.

- Rate Ceiling Facility – If the goal to prevent rate spikes, the Fed can set the RP rate 25 or 50 basis points above the upper target rate. At the current target range, the RP rate would be set at 2.25% or 2.50%. Those rates are low enough to prevent rate spikes but high enough to avoid becoming an everyday funding tool for market participants

- Better Manage Rates – If the Fed wants to fine tune Repo rates, keeping them within the target range, they can set the RP rate at the upper target rate. At the current range, that would be 2.00%. With the Fed willing to inject billions of dollars of cash in the market at 2.00%, Repo rates would rarely trade above 2.00%. The drawback is that it would appear the Fed is funding leveraged market participants. Lending cash to speculators (Gasp!). Such a tight spread is probably a no-go

2. More Quantitative Easing (QE)?

QE is a monetary policy and is not a tool to provide liquidity to the Repo market. It should not be a part of managing overnight interest rates.

3. Eliminate Interest On Excess Reserves (IOER)

The Fed should continue to pay interest to banks on required reserves but stop paying interest on excess reserves. That will get more cash out of the Fed and into the market. Why should private investors (banks) receive a market rate of interest investing with the government (the Fed)? Added bonus – the Fed will no longer need to keep tweaking the IOER rate.

4. Continue RP Operations

Back a few months ago, I recommended in my Repo Market Commentary that the Fed resume RP operations instead of initiating a permanent RP Program. “Bring back the System RP!” I wrote. My recommendation stands. I don’t believe a permanent facility is needed. RP operations give the Fed flexibility – they can choose overnight or term, choose the timing, and even enter the market twice in one day if necessary. The downside is that Fed overnight and term RP operations stress Primary Dealer bank balance sheets – balance sheets that are already restricted by bank regulation. Could the Fed open the RP operations to other financial institutions? Like the RRP Program?

Tyler Durden

Tue, 10/08/2019 – 15:28

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2IA8Otv Tyler Durden