“Don’t Panic”: CRE Crisis Hits The UK As Largest Property Fund Suddenly Halts Redemptions

Earlier this week, ECB vice president Luis De Guindos, speaking in an interview with El Mundo, offered a surprisingly candid take on how the ECB is distorting capital market, saying that while “we can still increase bond purchases or lower interest rates further, which means that we still have the same tools available” he added that “what is happening is that the secondary effects are becoming more tangible.”

Specifically, De Guindos said he is “worried by risk taking in the asset management sector against the background of low interest rates.” According to the ECB VP, the risk is that “supervision in this sector is not comparable with that in the banking sector. There is a risk. If they are asked for units to be paid out they have to do so within two or three days. I see a potential risk of liquidity imbalance. That is what worries me the most at the moment.”

De Guindos’ warning was spot on, because just a few hours earlier, UK fund manager M&G announced it had suspended redemptions and trading in its £2.5 billion Property Portfolio, which is marketed to retail investors, after it was unable to sell properties fast enough, particularly given its concentration on the retail sector, to meet the demands of investors, and was facing “unusually high and sustained outflows” it blamed on Brexit and the retail downturn.

As the FT reported, the M&G fund was the first major open-ended property fund to halt redemptions in this way since the crisis in the sector that caused seven funds to “gate” in 2016 following the Brexit referendum — which we profiled three years ago as one of the most high-profile market consequences of the vote to leave the EU.

First, a little history: first it was the shocking junk bond fiasco at Third Avenue which led to a premature end for the asset manager, then the three largest UK property funds suddenly froze over $12 billion in assets in the aftermath of the Brexit vote; two years later the Swiss multi-billion fund manager GAM blocked redemptions, followed by iconic UK investor Neil Woodford also suddenly gating investors despite representations of solid returns and liquid assets, then it was the ill-named, Nataxis-owned H20 Asset Management decided to freeze redemptions; finally Arrowgrass joined the list when it wrote down the value of an illiquid investment (the Dramland amusement park) by a whopping 70% overnight.

By this point, a pattern had emerged, one which Bank of England Governor Mark Carney described best when he said that investment funds that promise to allow customers to withdraw their money on a daily basis are “built on a lie.” At roughly the same time, the chief investment officer of Europe’s biggest independent asset manager agreed with him, because while for much of 2019 the biggest risk bogeymen were corporate credit, leveraged loans, and trillions in negative yielding debt, gradually consensus emerged that investment funds themselves – and specifically their illiquid investments- gradually emerged as the basis for the next financial crisis.

“There is no point denying we are faced with a looming liquidity mismatch problem,” said Pascal Blanque, who oversees more than 1.4 trillion euros ($1.6 trillion) as the CIO of Amundi SA, adding that the prospect of melting liquidity is one of “various things keeping me awake at night.”

* * *

Fast forward to today, when in what may be the first harbinger of a UK commercial real estate crisis, M&G, a London-listed asset manager, said it has been unable to sell properties fast enough, particularly given its concentration on the retail sector, to meet the demands of investors who wanted to cash out. The investor “run” led the fund to suspend any redemption requests in its £2.5 billion ($3.2 billion) Property Portfolio arriving after midday on Wednesday.

“In recent months, unusually high and sustained outflows from the M&G Property Portfolio have coincided with a period where continued Brexit-related political uncertainty and ongoing structural shifts in the UK retail sector have made it difficult for us to sell commercial property,” M&G said in a statement.

“Given these circumstances, we have now reached a point where M&G believes it will best protect the interests of the Funds’ customers by applying a temporary suspension in dealing.”

In addition to Brexit worries, M&G’s fund has been hit by its large holdings in retail property, a sector hit by retailer failures and value drops. According to the FT, the fund – which shrunk by £1.1 billion so far this year – holds 37.5% of its portfolio in retail warehouses, shopping centres, designer outlets and standard retail, based on its latest fact sheet, plus another 2.5% in supermarkets, a more stable part of the sector. The same fund was suspended in July 2016 for four months following the UK’s EU referendum when money flooded out of such funds.

Shares in the company dropped 2.6 per cent to 227.8p following the news, while the value of the property portfolio fund tumbled to the lowest level in 6 years.

Investors in the fund range from armchair, retail investors to institutional investors, dealing with millions of pounds according to the BBC. The fund waived 30% of its annual charge to investors, as they were unable to access their money, although some have called for action from the regulator on such charges.

The decision to suspend the fund, and its feeder fund, was taken by its official monitor – its authorised corporate director – and the City watchdog has been informed.

“The FCA is working closely with the firms involved to ensure that timely actions are undertaken in the best interests of all the fund’s investors,” a spokesman for the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) said.

M&G said the suspension would be monitored daily, formally reviewed every 28 days, and would only continue “as long as it is in the best interests of our customers”. This will allow assets to be sold over time, rather than as a fire sale, in order to meet investors’ withdrawal demands. The firm has written to investors to explain the current situation.

UK investors had been shaken in recent months by the demise of previously lauded fund manager Neil Woodford. Woodford Investment Management is in the process of shuttering after Woodford, one of the UK’s most iconic investors, was fired from its flagship fund in October. The case raised questions regarding the oversight of funds which invest in assets that take a long time to sell, but from which investors can withdraw their money from at any time.

The M&G case will make the case stronger for regulators to take a tougher stance on these types of investments.

Meanwhile, investors in the UK have been pulling their money out of other large so-called open-ended property funds, and the FCA has recently introduced daily monitoring of property funds. Yet financial planners have mixed views on whether the M&G suspension could be matched by other funds in the sector.

“Property is a long-term investment and we urge investors not to panic,” said Patrick Connolly of financial advisers Chase de Vere; of course the only word that investors would hear in that sentence is “panic” and there will be a flood of redemptions across the entire investing universe, potentially starting a domino-like freeze up of property funds, similar to that seen in 2016 in the days following Brexit.

“While the M&G fund is suspended, most other providers have far greater liquidity, and less exposure to retail properties, and so are better placed to meet redemptions, as long as there isn’t a mad rush to the exit door.

“Property still remains an asset class which can play an important role in investment portfolios and, when we have some real clarity on Brexit, the prospects for this asset class will hopefully improve.”

However, Ryan Hughes, from AJ Bell, said investors would review their interest in other funds which could lead to “a rush for the exits”. “We could see a wave of suspensions now – several that offer daily redemptions are at risk,” he said.

* * *

Ryan, is of course, right and whether he knows it or not he just described what we previously called a $1.6 trillion ticking time bomb in the market. While we previously discussed “The $1.6 Trillion Ticking Time Bomb In The Market“, the M&G fiasco is merely the latest example of how pervasive investment in hard-to-mark illqiuid assets have become in Europe where money managers from Neil Woodford to H2O Asset Management have come under fire from politicians, regulators and investors. But really it’s the central bankers’ fault: having injected trillions in the market to crush yields and push investors into the riskiest assets, investment firms have had no choice but to venture into harder-to-sell assets such as real estate in a search for yield.

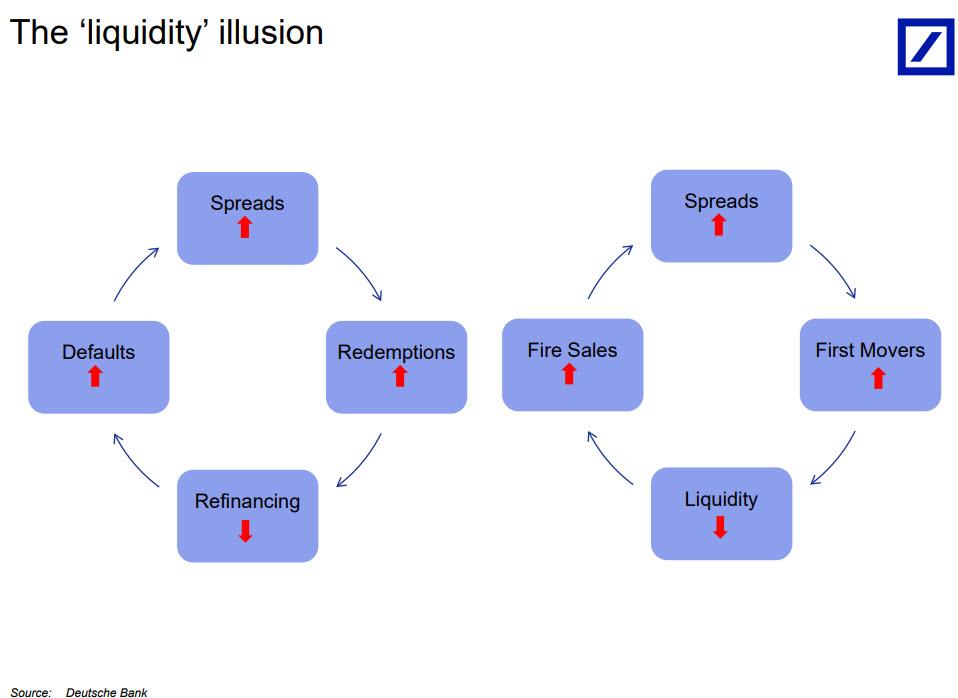

Incidentally, for those wondering if liquidity remains an illusion – a test that can only be confirmed when there is a crash and the market is indefinitely halted, an outcome that is now virtually inevitable – Deutsche Bank has a simple test: it all has to do with the sequence of events unleashed by widening spreads, where redemptions and first movers rush to sell, collapsing the market’s liquidity, freezing refinancings, and resulting in a surge in defaults and firesales, which in turn leads to even wider spreads and so on, until central banks have to step in to short circuit this toxic loop.

This also explains why GAM, Woodford, H20, Arrowgrass and many more funds (in the near future), will be similarly gated once their investors discover there is no liquidity to sell into and the only “real time” liquidity is offered to those who have a “first seller mover advantage”, to wit:

- If investors anticipate severe losses on the fund’s investments, they could be incentivised to “run for the exit” to be the first to redeem their shares.

- The first-mover advantage in open-ended funds arises because losses on asset sales to meet redemptions are incurred by investors which remain in the fund.

- As in a ‘bank run’, the asset manager is, in principle, forced to sell assets in a fire sale in order to meet its short-dated liabilities

This dramatic imbalance of asset holdings at market making banks and buyside “bagholders” of illiquid securities, is now posing a major problem for regulators, something the Bank of England acknowledged in a working paper published earlier this month, and highlighted by Mark Gilbert, to wit: “as the funds industry has supplanted banks as a source of credit in the past decade, households and companies have benefited from a useful alternative source of financing. But, the report warned, we don’t know how this market-based system will respond under stress.”

Modelling such a scenario “can generate an adverse feedback loop in which lower asset prices cause solvency/liquidity constraints to bind, pushing asset prices lower still,” the BOE found. In other words, the new market structure may be worse than the old.

The feedback loop discussed by the BOE is the one we showed in the chart above.

And, as recent notable fund “gates” and/or collapses have shown, the difficulty for asset managers in such an eventuality is finding sufficient cash to repay exiting investors while preserving the structure of the portfolio without distorting market prices, according to Amundi’s Blanque.

According to Bloomberg, part of Amundi’s response to this seemingly intractable issue is to include liquidity buffers in its portfolios, which may mean holding securities such as German bunds and U.S. Treasuries, which should always trade freely. But the industry needs to come up with a common definition so that liquidity is included along with risk and return when assessing a portfolio’s robustness, Blanque says. Additionally, this band aid only works for modest redemptions. A wholesale liquidation would crush even the most “buffered” up fund.

For now, asset managers have to cope with what Blanque called “the sacred cow” – although a better phrase would be “constant risk” of allowing clients to withdraw funds on a daily basis.

“It is a bomb, given the risks of liquidity mismatch,” he warns. “We don’t know if what is sellable today will be sellable in six months’ time.”

That’s not the only we don’t know. As Blanque concluded, “we don’t know the channels of transmission, we don’t know how the actors will act. It is uncharted territory.”

And that, precisely, is why central banks can never again allow risk asset prices to drop: the alternative means gating not one, or two, or a hundred funds, but halting the entire market, because once everyone start selling and price discovery finally returns to a market that has been dominated by central banks for the past decade, several generations of traders and investors who have grown up without price discovery will be shocked to discover just where “fair” market prices reside.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 12/04/2019 – 11:26

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/34O1UtH Tyler Durden