China’s Pork Hyperinflation Hits A Record 110%, Keeping Credit Growth In Check

At a time when Beijing is bracing to reveal to the world that China’s economic growth has dipped below 6% for the first time in modern history (and in reality is about half that), and the PBOC is desperate to find ways to stimulate the economy without causing another mini debt bubble, the world’s most populous nation continues to face a major hurdle: pork hyperinflation.

As was revealed in the latest inflation data, China’s CPI accelerated further to 4.5% Y/Y in November, well above the 4.2% consensus expectation, and the highest annual increase since 2011, driven by higher inflation in fresh vegetable and hyperinflation pork prices. The silver lining: the surge in China’s price basket may be easing as on month-over-month terms headline CPI inflation moderated to +8.2% (seasonally adjusted annual rate) in November from +9.1% in October.

As has been the case for the past year, the culprit behind the headline CPI surge was food inflation, which accelerated further to a record +19.1% in November from +15.5% in October, primarily on higher inflation in fresh vegetable and pork prices.

And as iw well-known by now, the driver for surging food inflation remains China’s history pork shortage which in November sent prices surging further, rising to a mindblowing 110.2% yoy in November from 101.3% yoy in October, pushing up headline CPI inflation by around 0.2pp relative to October (although the sequential increase slowed).

A new development in November, this time it wasn’t just pork prices as inflation in fresh vegetable rebounded to +3.9% yoy from -10.2% yoy in October, driving headline CPI inflation up by another 0.4%.

The silver lining: non-food CPI inflation remained relatively low at 1.0% yoy.

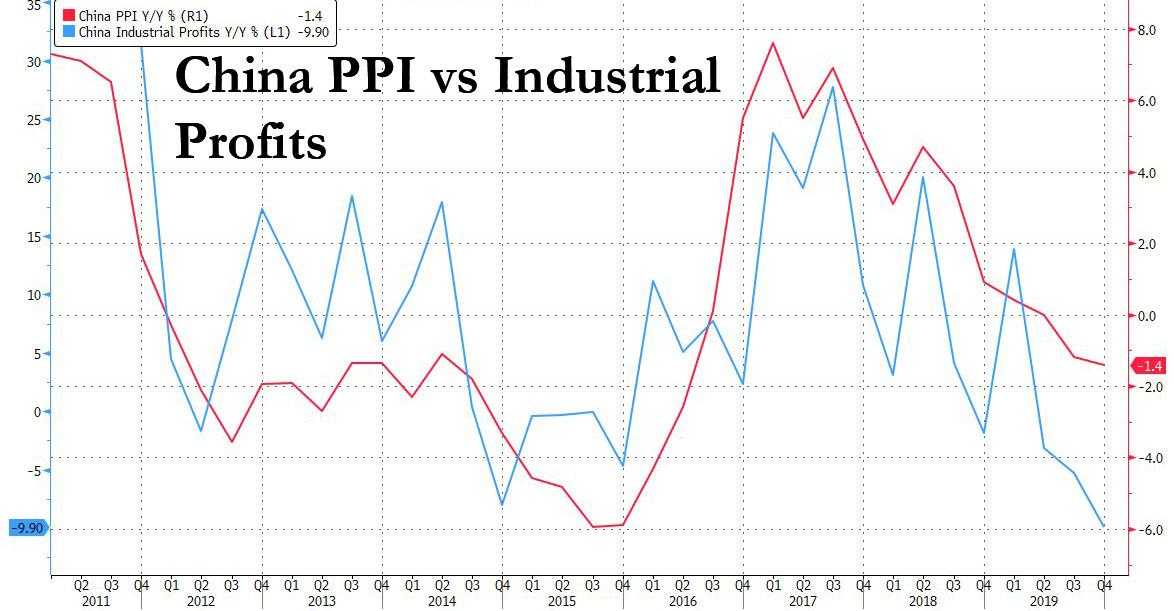

Looking at the other side of the ledger, the just as important for China’s companies PPI print printed negative again although the deflation narrowed slightly to -1.4% in November, from -1.5% in October. Deflation in the petroleum industry lessened the most, though partially offset by lower inflation in coal mining.

The reason why PPI is so important is because there is a direct correlation between Chinese industrial profits and factory gate prices, or in this case PPI deflation. And absent a rebound in PPI, China’s corporate sector – already loaded to the gills with debt – will face growing bankruptcy pressures as declining cash flows will increasingly be unable to meet debt service payments.

The problem: as long as CPI is soaring, the PBOC’s hands are generally tired in how much monetary stimulus it can inject. And as Goldman notes this morning, “headline CPI inflation is likely to remain elevated in the coming months” as high frequency data suggest year-on-year inflation in pork prices has remained high in early December, though moderating somewhat. Prices in fresh vegetables have picked up further in early December in year-on-year terms. Elevated inflation could be one factor that may limit the room for front-end rates to decline in coming months.

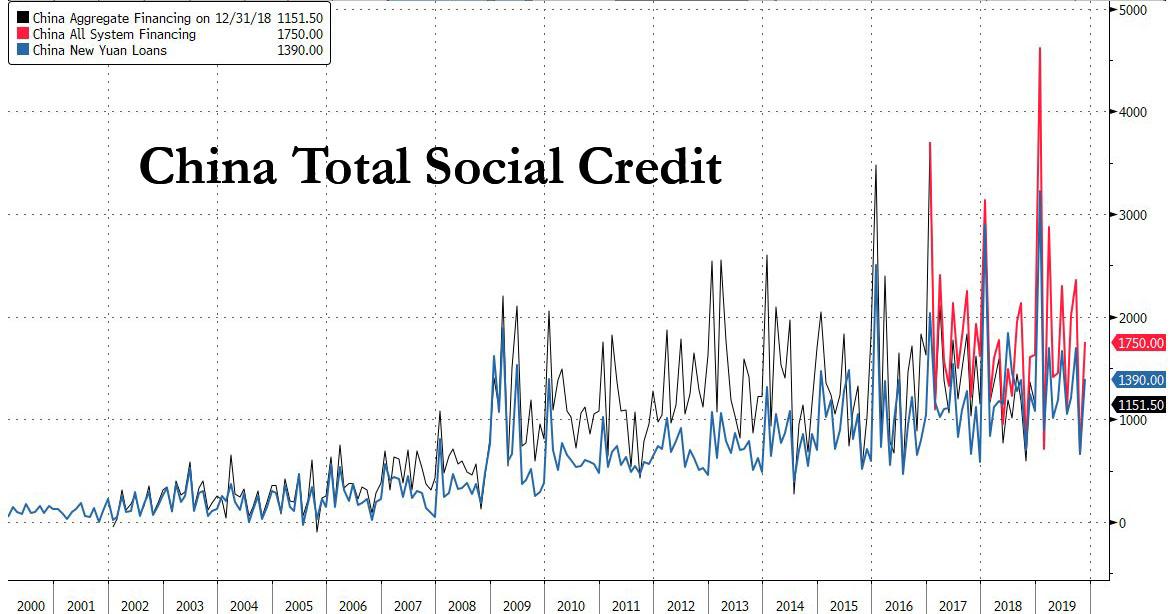

And as China’s “stimulative” hands remain tied, the latest Chinese credit growth data confirmed that Beijing can only do so much to spur much needed inflation. And while credit data surprised modestly to the upside in November after the record low October print, likely helped by administrative push to lend in November, the Total Social Financing was still a relatively modest, by historical standards, 1.750 trillion, even as shadow banking shrank for the 8th consecutive month.

Here are the details from Goldman:

New CNY loans: 1390BN yuan in November, higher than consensus 1200 BN, representing outstanding CNY loan growth of 12.4% in November, the same as October.

Total social financing: 1750BN yuan in November, also well above consensus 1485BN yuan, and more than double October’s paltry 662BN yuan.

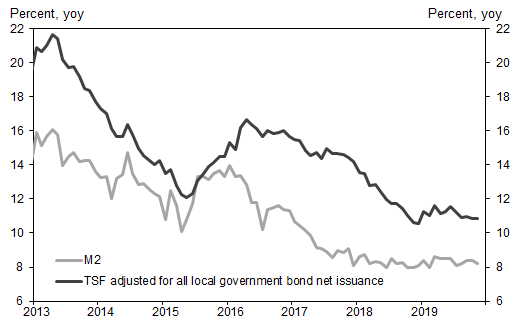

According to the PBOC, TSF stock growth was 11.1% yoy in November, the same as October. If we add all local government bond net issuance to TSF flow data, Goldman estimates adjusted TSF stock growth edged up to 10.9% yoy in November from 10.8% in October. The implied month-on-month growth of adjusted TSF accelerated to 10.3% (seasonally adjusted annual rate) from 9.5% in October.

Finally, even though TSF posted a much needed rebound, one can’t say the same for the all important M2, which rose just 8.2% Y/Y in November, missing Bloomberg consensus of 8.4%, and down from October’s 8.4% Y/Y.

So while credit data surprised modestly to the upside in November as RMB loan growth momentum picked up and Banker’s acceptance bill issuance reversed the contraction in October and corporate bond issuance accelerated, the decline in trust and entrusted loans -i.e., shadow debt – continued to be a drag, and has been down for 19 of the past 21 months.

Commenting on the rebound in November credit growth, Goldman writes that “it potentially reflects the loosening intention of the government” and is driven by four factors:

- October activity data showed broad-based weakness,

- Policy makers were concerned (justifiably in retrospect) about further downward pressures from exports as there was widespread evidence of frontloading of exports until October

- a very weak October TSF data. This, amid the two factors above, likely put the central bank under more pressure to keep TSF growth at least stable. Given the weakness in October data, this likely meant a rebound was needed in November

- High frequency pork prices have been on a downward trend very recently. This potentially eased the concerns policymakers had about consumer inflation. Although CPI accelerated further in November on a year-over-year basis, it is the high frequency pork price data that matters more on a forward-looking basis, as it has been the single biggest driver of CPI.

As a result the central bank provided ample liquidity in the interbank market in November – but not too much lest food prices spike even more – and pushed commercial banks to lend out more. Other policymakers likely took actions to boost activity growth, especially administrative push to accelerate infrastructure construction. Warmer than usual weather conditions made this easier to do than otherwise since November is around the time of the year when large parts of northern China become too cold to construct some of these projects. These factors increased credit demand, although it is unclear if this relative credit “goldilocks” will persist. It all depends on whether China will find an alternative source of pork to restock its inventory as China’s population is becoming increasingly displeased with the soaring price of its favorite protein.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 12/10/2019 – 09:10

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2E2o9At Tyler Durden