Chinese Internet ‘Influencers’ Helped Sell More Than $4 Billion In Goods Last Year

Internet influencers are quickly becoming the new preferred type of advertising in China, mirroring a trend that has taken place in the U.S.

And the influencers run the gamut: from livestreaming moms, to farmers – and even dogs, according to the Wall Street Journal. These “key opinion leaders” sold more than $4 billion in goods in China in 2018, according to China’s largest influencer company, Ruhnn Holding.

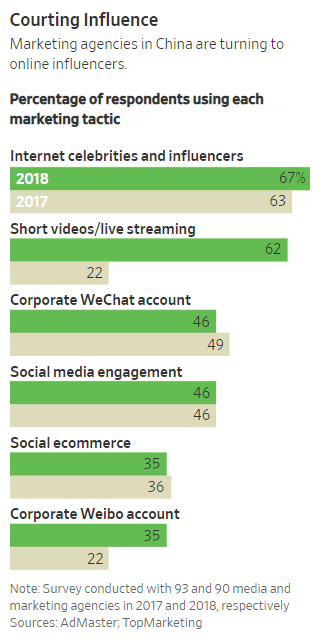

While that is still a small fraction of the $2 trillion in e-commerce sales that are expected out of China this year, it’s still an area that companies are paying attention too. 67% of advertisers this year said that internet celebrities and influencers have becoming their preferred method of advertising in China. Supporting the influencers is a new industry of producers and talent agencies, which has doubled in size over the last two years.

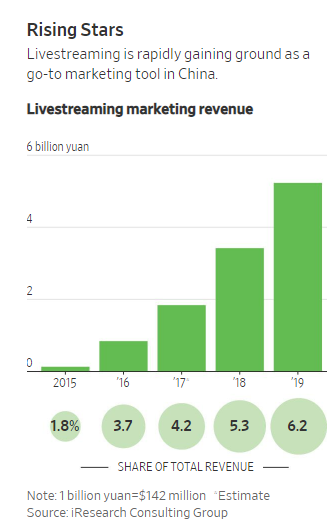

There are an estimated 21 million influencers in China and they have embraced livestreaming on platforms like Alibaba’s Taobao and Douyin, a version of TikTok. Although Amazon has started to look into livestreaming and influencer channels, livestreaming is still relatively new in the U.S. compared to China. In the U.S., most influencers use posts and short videos on YouTube and Instagram.

Consumers in China were the most susceptible to brand recommendations by influencers than any other country surveyed – partly because Chinese consumers have a long history of being cheated by counterfeit products. Many consumers say they trust online celebrities, who largely portray themselves as regular people, instead of websites or brands.

Mark Tanner, managing director of marketing-research firm China Skinny said: “It comes down to the inherent lack of trust by Chinese consumers. For many, Chinese KOLs are the most trustworthy and authentic source of information, particularly as there are relatively few other ways to get information with the state controlling the media.”

Brands like using online influencers because they are effective: roughly one in five consumers watching online infomercials will buy a product, compared to less than 1% of consumers viewing conventional e-commerce advertising.

Alibaba has invested heavily into influencers, broadcasting the shows of about 100,000 livestream hosts per day on its shopping app. Even leaders of China’s communist party have started to talk about ways to use influencers to reach out to the public.

But there are some downsides, too. Because customers feel close to the influencers they buy from, there can be swift outrage when a customer feels betrayed. For instance, one of China’s most famous influencers, Li Jiaqi, went viral for the wrong reason when he tried to fry an egg on a non-stick pan earlier this year and the egg stuck to the pan. He also went viral after claiming to sell “big meaty crabs” from Suzhou. When customers received the crabs, they found them to not be big, meaty or from Suzhou.

Searches for Li Jiaqi’s “misleading advertising” totaled 700 million hits after the incidents.

Deng Xuerui, who received 10 undersized crabs earlier this month said: “He betrayed my trust”. She said she used to watch his show daily but is now no longer a fan. State newspapers also piled on Jiaqi, suggesting that he was an example of why government regulation was necessary for influencers.

The work can be grueling for influencers, many of whom host shows live six or seven days a week. Regardless, pay can be good, as well. A key opinion leader can earn has much as $50,000 with one pre-recorded post on a social media site. In the U.S., big name stars can bring in as much as $100,000, as we noted in our recent writeup about the influencer trend in the U.S.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 12/12/2019 – 22:25

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2PhDpQh Tyler Durden