China Premier Warns Of Economic Turmoil In 2020, Continued Deceleration Means Global Rebound Unlikely

Chinese premier Li Keqiang was quoted on state television by Reuters on Thursday as saying the economy could face tremendous downward pressure in 2020.

Li said the downward pressures could be even greater than what was seen in 2019; he made no mention of the possible trade resolution with the US would correct economic growth.

He said the government would implement monetary and fiscal policies to keep the economic expansion within a consistent range throughout 2020. This could be the latest confirmation that China’s GDP could slip underneath 6%.

A similar warning was echoed by an advisor to the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) last week, who said China’s economy might not recover for the next five years.

Liu Shijin, a policy adviser to the PBoC, said the country’s GDP will decelerate through 2025 and could print in a range of 5 to 6%.

Shijin warned that excessive monetary policy is failing to stimulate the economy and could cause it to decelerate in the year ahead.

Last month, we noted that China’s credit growth plunged to the weakest pace since 2017 as a continued collapse in shadow banking, weak corporate demand for credit, and seasonal effects all signaled that China’s economy, nevertheless, the global economy, will continue to slow in 2020.

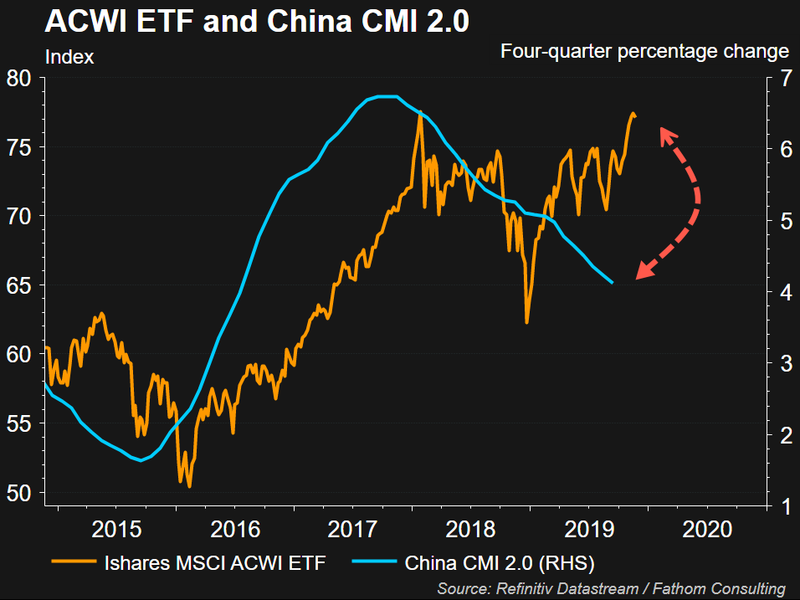

A further deceleration in China’s economy could ruin the party for equity bulls, who have already priced in a massive 2016-style rebound in the global economy for 1Q20. A slowing China means the world could fail to rebound, though we don’t discount the stabilization narrative.

With China’s economy unlikely to sharply rebound early next year, global investors could find themselves repricing growth in the near term as global equities are at all-time highs thanks to massive money printing by central banks.

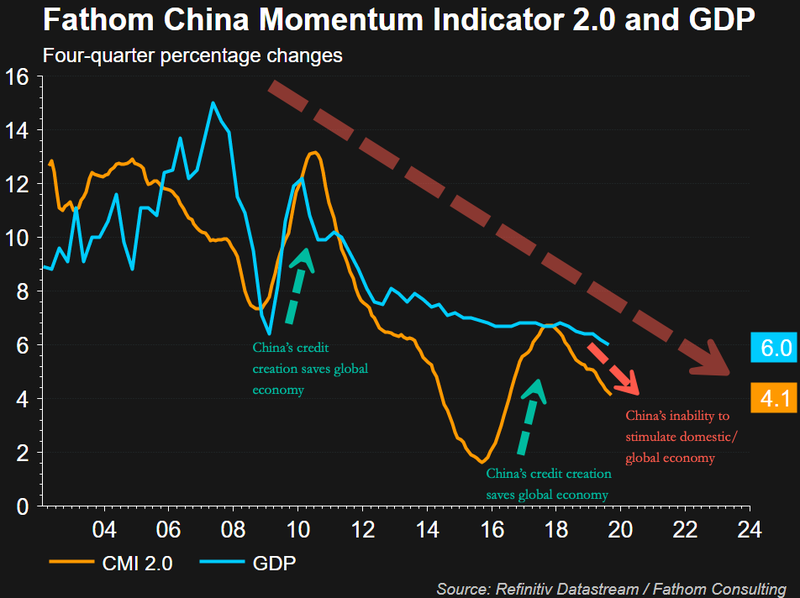

To gain more color on China’s extended slowdown, Fathom Consulting’s China Momentum Indicator (CMI) provides a more in-depth view of China’s economic activity than the official Chinese GDP statistics.

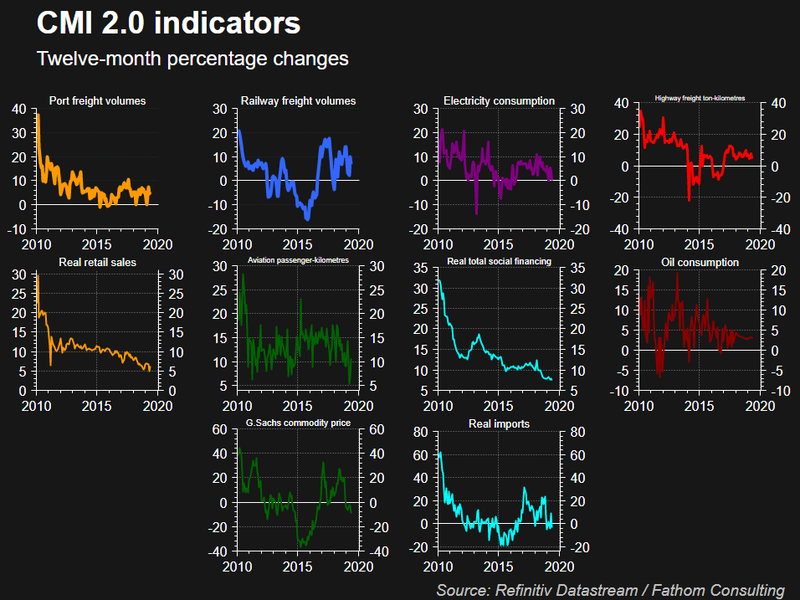

CMI is based on ten alternative indicators for economic activity; some of those indicators include railway freight, electricity consumption, and the issuance of bank loans.

Fathom has stated that in CMI, the calculation of the index avoids measuring construction activity, and instead focuses on shadow measures of economic activity. The consulting group says this allows the index to be “less prone to manipulation than the headline GDP figures.”

“In 2014, when China’s traditional growth model was running out of steam and vulnerabilities were rising, authorities toyed with credit tightening and an enforced rebalancing. But at the end of 2015, when growth slowed too sharply, they quickly threw in the towel, resorting to the old growth model of credit-fuelled growth. With growth once again slowing, and past precedent suggesting credit has neared its limit, China finds itself at a crossroad,” Fathom recently said.

China’s failure to stimulate its economy suggests CMI will continue a downward trajectory that has been underway for the last decade.

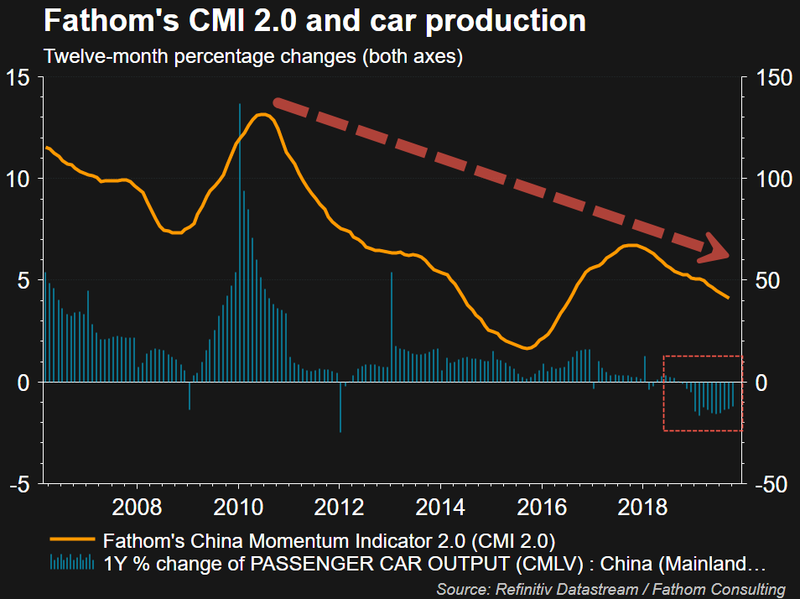

We’ve recently outlined the bust of the global auto industry has weighed down the Chinese economy. With no signs of an upswing in the auto market, China’s economy will remain depressed in the years ahead.

As China’s economy slows, global commodity prices are stuck in a deflationary spiral.

China’s slowing economy warns that global equities have mispriced growth for early 1Q20.

Looking for signs of life in the Chinese economy — there aren’t any at the moment.

Société Générale’s latest report shows employment in China contracting across manufacturing and non-manufacturing, outlining how the slowdown is broad-based.

Bloomberg has compiled a list of long-time China watchers that are warning about an extended slowdown.

George Magnus, a research associate at Oxford University’s China Centre and author of “Red Flags: Why Xi’s China is in Jeopardy:”

In the spirit of self-criticism, I’d say my best call on the economy was an early spot of the huge demographic shift that kicked off in earnest in 2012, an abiding assertion that China’s elevated growth rates could not be sustained, and anticipation of a financial crisis that turned up in 2015-16. Worst call was thinking that crisis might turn into a ‘Minsky Moment’ for China, as per 2007-08, and failing to integrate properly the tools the state has to prevent catastrophic failure.

I expect China to flirt with officially recorded growth of around 6%, but the reality is that the tempo of growth is ratcheting down to somewhere between 3% and 4%. In 2020, perhaps 5.8% to 6%, officially, not least because the economic news has to remain upbeat ahead of the CCP centenary in 2021. The consequences of over-indebtedness, demographic change, inadequate wealth transfer and income redistribution policies, and stagnant total factor productivity growth associated with institutional flaws are the main drags on growth. The 2020s will be a challenging time for China.

Jim O’Neill, the former Goldman Sachs Group chief economist who coined the term BRIC:

The BRICs path assumed China would grow 5% a year in the decade 2020-29 and I have no reason for changing this. If it does, and so long as the renminbi doesn’t decline a lot in value, then by the end of the decade, China will be very close to being as big in current dollar terms as the US.

As this decade nears its end, China has major problems positioning itself in the world. As evidenced by the Uighur situation, China’s approach to life now gets much more global attention than when it was smaller. In the coming decade, China has to somehow develop a more subtle and sophisticated stance on many of these issues, and I am not sure Beijing fully realizes this yet.

Edward Yardeni, president and chief investment strategist at Yardeni Research:

Demography is starting to really weigh on China’s growth. China is rapidly evolving into the world’s largest nursing home.

They are going to have to provide a social safety net for these folks who are going to get older and need health care. If they don’t do that, they are going to depress their consumers. When you want to be a superpower, there are a lot of factors that matter, and demography is certainly one of them.

The biggest takeaway is China produced 60% of the world’s debt over the last ten years and is the biggest driver in global economic growth. A slowing China means the global economy will likely remain stagnate in 2020.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 12/19/2019 – 21:05

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2SbR2Tc Tyler Durden