Alarming NYT Op-Ed Reveals “Disturbing” Secretive Surveillance State Powered By Your Phone’s Location Services

Millions of Americans are walking around with phones that have, unknowingly, created one of the most disturbing and unintentional “surveillance states” to ever exist.

A explosive new opinion piece in the NY Times aims to demonstrate that detailed smartphone tracking is far more ubiquitous than many think, despite the ongoing claims by companies that people’s data is “anonymous”.

Paul Ohm, a law professor and privacy researcher at the Georgetown University Law Center, said that describing location data as anonymous is “a completely false claim that has been debunked in multiple studies.”

He added: “Really precise, longitudinal geolocation information is absolutely impossible to anonymize. D.N.A. is probably the only thing that’s harder to anonymize than precise geolocation information.”

The op-ed looked at trying to identify people in positions of power. It identified and tracked “scores” of notable people, like military officials with security clearances, as they drove home at night. They also tracked law enforcement officials and high powered lawyers. Though they didn’t name any of the people, they followed them on private jets, vacations and taking their kids to school.

Despite some of the data pointing to “scandal and crime”, the purpose of tracking them was to document the risk of under-regulated surveillance.

One person identified was Mary Millben, a singer based in Virginia who has performed for three Presidents. When told her phone was putting her “on the map” for everyone to see, she said: “To know that you have a list of places I have been, and my phone is connected to that, that’s scary. What’s the business of a company benefiting off of knowing where I am? That seems a little dangerous to me.”

She couldn’t name the app that shared her location, despite saying she was “careful” about which apps she allowed to share her location.

“That makes me uncomfortable. I’m sure that makes every other person uncomfortable, to know that companies can have free rein to take your data, locations, whatever else they’re using. It is disturbing,” she continued.

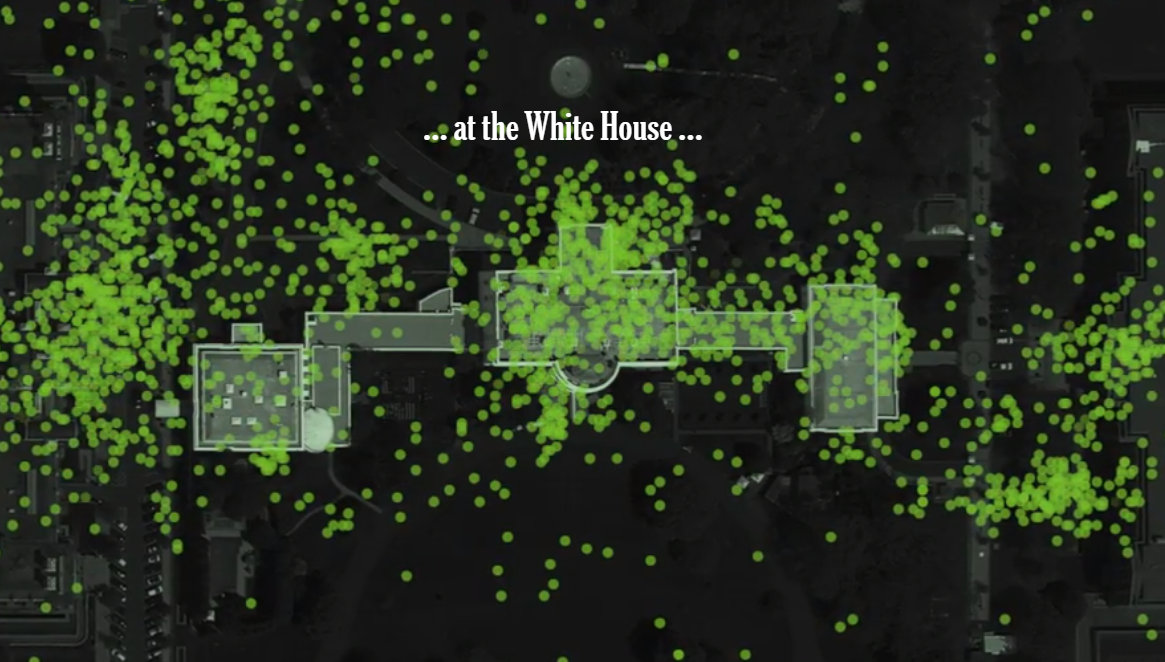

On inauguration weekend, the authors were able to track “elite attendees at presidential ceremonies, religious observers at church services, supporters assembling across the National Mall”, as well as protesters. They even spotted a senior official at the DOD walking through the Women’s March, along with his wife.

Yet companies that take your location data collect “orders of magnitude” more that what the Times opinion writers had access to.

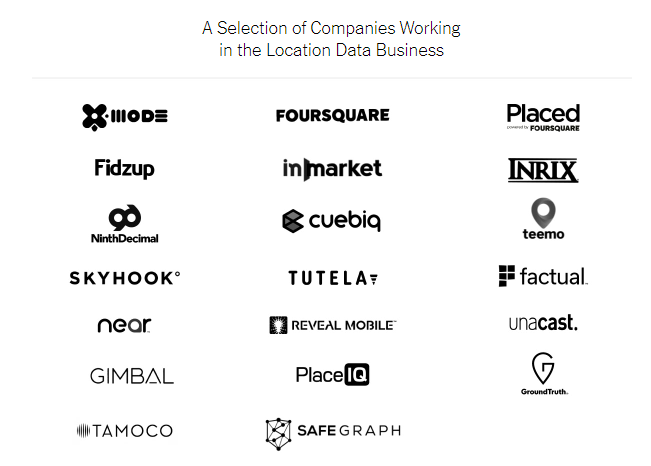

There are dozens of companies out there that profit from this data. Many use “technical and nuanced language that may be confusing to average smartphone users.” Many company names would likely be unfamiliar to most Americans.

These companies downplay the risks of collecting such revealing data at scale. Brian Czarny, chief marketing officer at Factual, one such company, said: “No, it doesn’t really keep us up at night. Factual does not resell detailed data like the information [The Times] reviewed. We don’t feel like anybody should be doing that because it’s a risk to the whole business.”

But without federal privacy laws, the industry has largely been self-regulated. Several groups have offered ethical guidelines and groups like the Mobile Marketing Association are drafting pledges to improve this self-regulation.

But states are starting to respond. For instance, the California Consumer Protection Act takes effect next year and allows residents to ask companies to delete their data or prevent its sale. But legally, the law could leave the industry free to do whatever it wants.

Calli Schroeder, a lawyer for the privacy and data protection company VeraSafe said: “If a private company is legally collecting location data, they’re free to spread it or share it however they want.”

Companies are required to disclose “very little” about data collection, but rather are only required to describe their practices in their privacy policies.

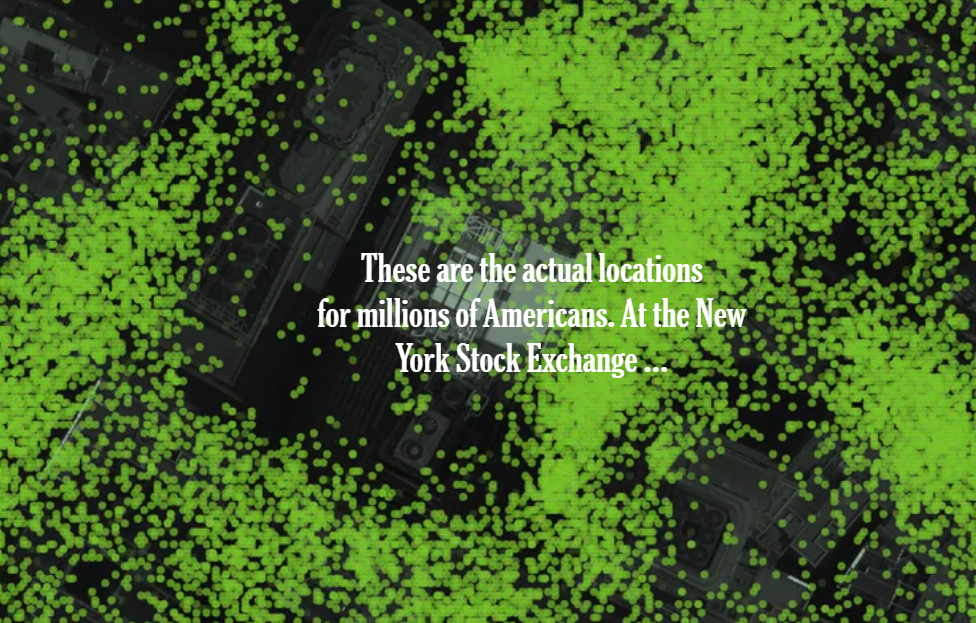

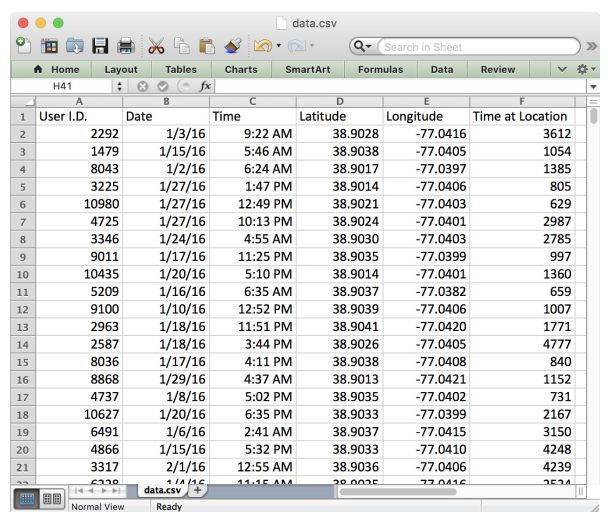

Location data, gathered by latitude and longitude, coupled with time spent in an area, feed a lucrative secondary business of analyzing, licensing and transferring that information to third parties. Here’s what that data looks like:

The data provides intelligence for big businesses, as well:

The Weather Channel app’s parent company, for example, analyzed users’ location data for hedge funds, according to a lawsuit filed in Los Angeles this year that was triggered by Times reporting. And Foursquare received much attention in 2016 after using its data trove to predict that after an E. coli crisis, Chipotle’s sales would drop by 30 percent in the coming months. Its same-store sales ultimately fell 29.7 percent.

Companies like Verizon and AT&T have been selling the data for years. Last year, Vice found that data being sold was being used by bounty hunters to find specific cell phones in real time. Telecom companies pledged, after the scandal, to stop selling the data. But there is still no law that prevents it.

Additionally, the piece notes “everything can be hacked”. That means that any server that houses this data is susceptible to having it wind up in the wrong hands.

For most Americans, the distribution of this information could result in embarrassment or inconvenience. But for people like survivors of abuse, it could come with substantially more risks.

And the ability to identify individuals was stunning:

In one case, we observed a change in the regular movements of a Microsoft engineer. He made a visit one Tuesday afternoon to the main Seattle campus of a Microsoft competitor, Amazon. The following month, he started a new job at Amazon. It took minutes to identify him as Ben Broili, a manager now for Amazon Prime Air, a drone delivery service.

Broili commented: “I can’t say I’m surprised. But knowing that you all can get ahold of it and comb through and place me to see where I work and live — that’s weird.”

He continued: “It’s an awful lot of data. And I really still don’t understand how it’s being used. I’d have to see how the other companies were weaponizing or monetizing it to make that call.”

You can read the full long form op-ed here.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 12/19/2019 – 23:05

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/34Hu3lg Tyler Durden