The Fed Has Repeated The Mistake Of 1998 Which Ended With The Dot Com Bubble

Submitted by Joseph Carson, Former Director of Global Economic Research, Alliance Bernstein

The Politics of “Tariffs” & The Fed

The Trump administration used the hammer of tariffs to negotiate a bi-lateral trade agreement with China, but in doing so also influenced a change in domestic monetary policy. The tariff-led negotiations were part of Trump’s team trade strategy, but were the tariffs also a tool to persuade a change in monetary policy? Whether it was or not, the Fed has now unwittingly entered into symbiotic relationship with fiscal policy and questions over autonomy could very well influence future policy decisions jeopardizing financial stability in the process.

Tariffs and the Fed

The Federal Reserve does not have a seat at the table when fiscal policy decisions like the imposition of tariffs are implemented. As a result, policymakers are forced to accept fiscal policy decisions, like tariffs, as an input into their economic forecasts and policy deliberations.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell stated that although monetary policy “cannot provide a settled rule book for international trade” monetary policy must take into account how trade disputes are affecting the economic and inflation outlook and adjust monetary policy to meet the mandated objectives.

From a risk management perspective policymakers always enjoy the policy flexibility to take out an “insurance policy” against unknown risks and outcomes. And in the case of the US and China trade dispute with an unknown outcome and time limit it was not unreasonable for policymakers to take out an “insurance policy”. Yet, the main question is how long should an “insurance policy” remain in place when the evidence shows that the perceived economic and financial risks did not materialize?

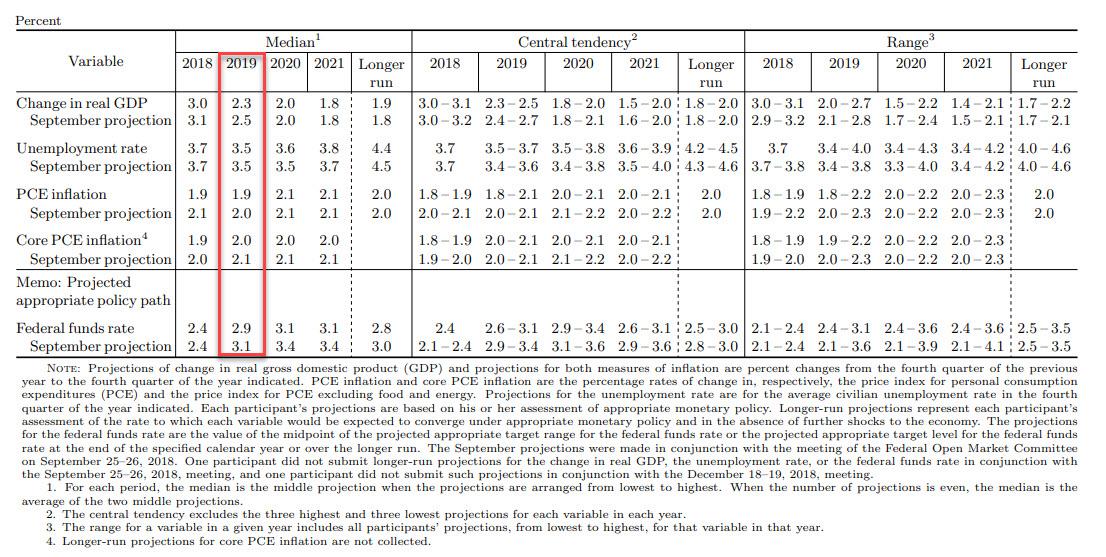

Despite all of the concerns over potential fallout from US and China trade dispute the US economy’s performance in 2019 was almost exactly in line with policymakers expectations. To be sure, real GDP growth of 2.4% essentially matched policymaker’s forecast of 2.3% and expectations on unemployment rate (3.5%) and core inflation (1.9%) were very close to the actual outcomes of 3.6% and 1.7% respectively.

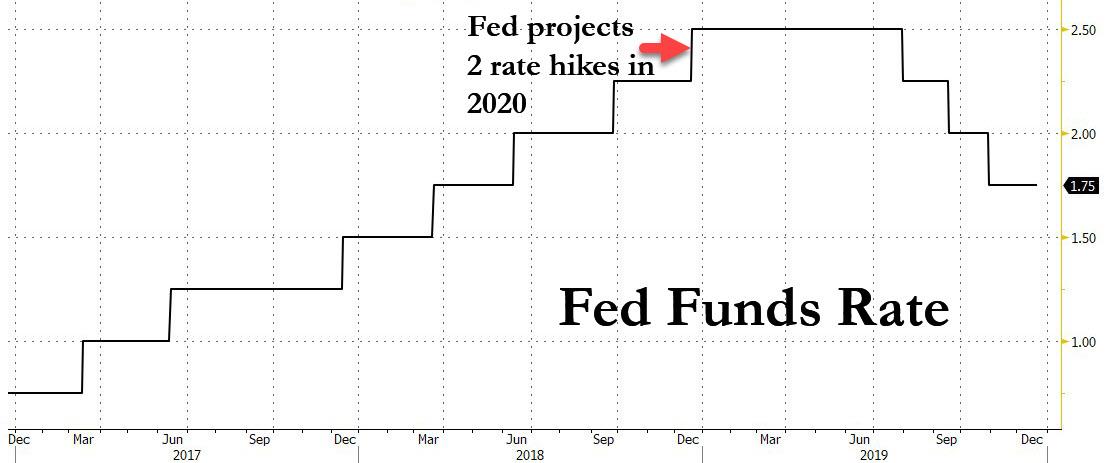

Nonetheless, even with nearly “perfect” forecasting record for 2019, policymakers went against their initial intentions of hiking rates twice over the course of the year and instead lowered rates three times.

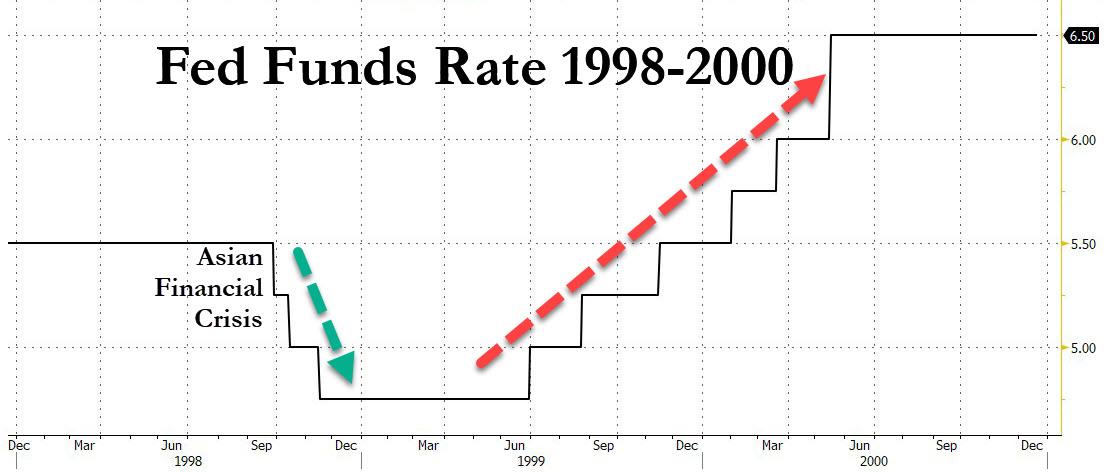

From a monetary policy, domestic economy and financial markets perspective 2019 is analogous to that of 1998.

- First, in 1998 policymakers were concerned about how the storm clouds from Asian financial crisis could impact the export performance of US companies, exerting a discernible drag on the economy. In 2019, policymakers saw the US and China trade dispute weighing on export growth and business investment. As such, in both periods policymakers decided to lower official rates three times to cushion the impact on the domestic economy.

- Second, in 1998 and in 2019 the overall domestic economy performance was unaffected by the global trade issues; both periods experienced solid gains in consumer spending, with the jobless rate falling to decade lows.

- Third, in 1998 and in 2019 the financial markets experienced periods of risk-off directly linked to global issues, but the injection of additional liquidity from the reduction in official rates triggered powerful rallies.

In the late 1990s, policymakers possessed a high degree of independence and there were little, if any, public political suggestions or demands of what to do. Yet, policymakers operating even without any political interference made a “huge” policy mistake as they left easy money in place far too long resulting in finance racing far ahead of the economy as equity prices and corporate debt soared to record levels while operating profits were declining. The end result was a finance-driven recession.

The risk that policymakers repeat the mistakes of the late 1990s is very high.

- For one, policymakers are overlooking the possibility once gain that its easy money policy is distorting the financial markets.

- Second, the independence of the Fed has never been more threatened and the new role of being an accomplice in fiscal policy decisions is an inherently a political one, and one that policymakers will find hard to exit anytime soon.

Investors are betting that nothing changes in 2020, but the risks of financial excesses creating financial instability are rising. Volatility in politics and market rates could very well be the surprise in 2020.

Tyler Durden

Sun, 12/22/2019 – 14:15

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2ZfGWBZ Tyler Durden