World Bank Warns “Wave Of Debt” Could Unleash Historic Crisis, Crush The Global Economy

Something happens to the world’s “really smart people” when the topic of debt is discussed: they become blabbering idiots.

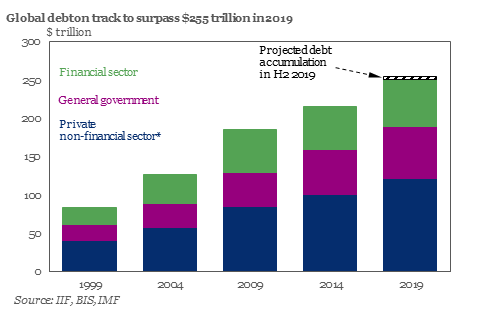

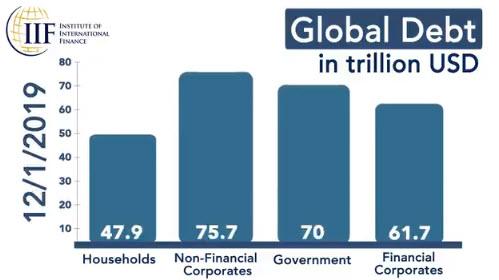

Consider that last month we reported that according to the Institute of International Finance, global debt has now hit $250 trillion and is expected to rise to a record $255 trillion at the end of 2019, up $12 trillion from $243 trillion at the end of 2018, and nearly $32,500 for each of the 7.7 billion people on planet. “With few signs of slowdown in the pace of debt accumulation, we estimate that global debt will surpass $255 trillion this year,” the IIF said in the report.

Separately, Bank of America recently calculated that since the collapse of Lehman, government debt has increased by $30tn, corporates debt by $25tn, household by $9tn, and financial debt by $2tn; And with central banks expected to support government debt, BofA warns that “the biggest recession risk is disorderly rise in credit spreads & corporate deleveraging.”

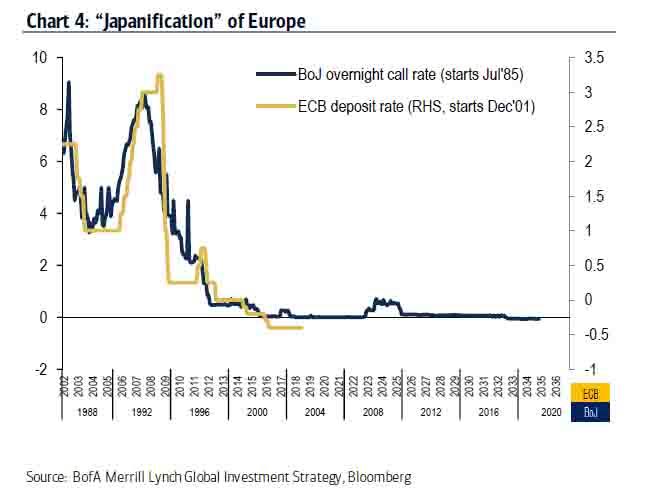

Where the “really smart people” come in, is the periodic return every couple of years of the naive assumption that despite this relentless increase in global debt, central banks can tighten financial conditions and the world can sustain higher interest rates. What ends up happening is that after a few quarters of “reflation” – which ironically and circularly is critical to inflate the debt away – markets realize that higher rates on this mountain of debt are unsustainable, risk assets tumble and central banks are forced to unleash another wave of easing, in the process further Japanifying first Europe, and then the entire world.

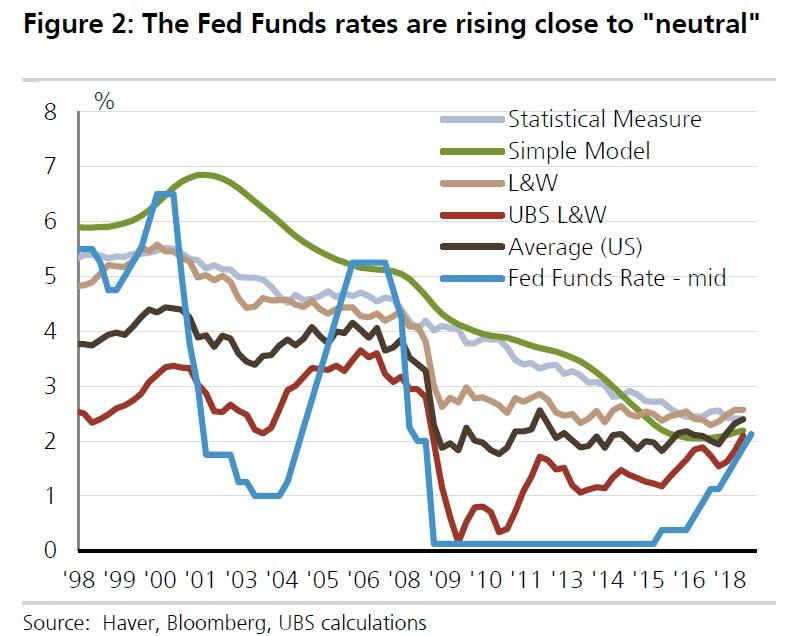

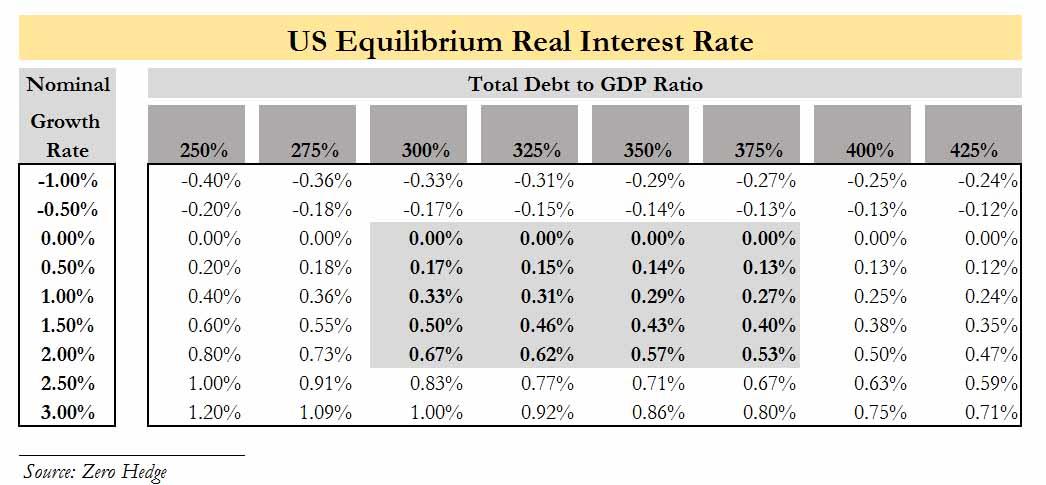

Only the “really smart people” they don’t use simple logic like that, and instead they call it a “mysterious” (and relentless) decline in the r-star (r*), “equilibrium” or neutral rate of interest…

… which is basically another way of saying that as the world’s massive debt mountain grows, the maximum possible interest rate shrinks with every passing year, something we first discussed in 2015 in “The Blindingly Simple Reason Why The Fed Is About To Engage In Policy Error“, in which we showed that the equilibrium rate is a simple function of just two variables: total debt/GDP and nominal GDP growth. And in a world where GDP growth is shrinking and total debt growing, it logically means that r-star has nowhere to go but down.

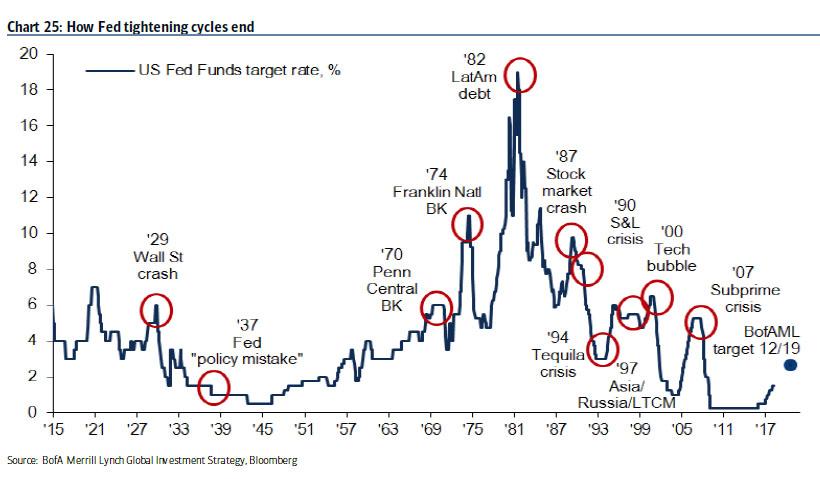

Yet none of this is obvious to the “really smart people” and as a result, every so often we get another controlled ‘reflation’ attempt which inevitably ends in a market dump just like Q4 2018 when rates rose too high – due to the latest failed attempt to normalize policy – and risk assets tumbled. What’s even more troubling, every crisis has a lower and lower threshold rate as shown in the next chart. it also explains why the Fed could barely hike to 2.5% before it was forced to promptly cut 3 times… and launch QE 4.

A simple extrapolation of the declining trendline in the chart below suggests that the Fed’s maximum interest rate will be 0% in just a few years.

Which brings us to the point where the “really smart people” become blabbering idiots. Because roughly at this time, instead of talking higher rates to stimulate the economy – which we just learned is no longer possible due to too much debt – the discussion turns to adding stimulating the economy…. by adding even more debt. Not unironically, Bloomberg recently published an article titled “The Way Out for a World Economy Hooked On Debt? More Debt. ” That such garbage merits even a remotely serious consideration is for three reasons: i) the “really smart people” need a narrative that doesn’t make them look like “really dumb people”, ii) that reflation as a way out of the current debt crisis is no longer possible, and iii) because even greater idiocy in the form of MMT, i.e., helicopter money, is gaining serious consideration among the world’s politicians (and even finance professionals), and may well become the dominant financial paradigm after the next crisis, a crisis which will then inevitably end with the long-overdue collapse of fiat currencies, because while central banks can’t orchestrate a controlled increase in 1 or 2% without losing control of risk assets, they can certainly bring about an uncontrolled hyperinflation once the world finally loses faith in the prevailing monetary orthodoxy.

And while the “really smart people” sound like absolute idiots once the unsolvable topic of debt comes around, it doesn’t mean that they can’t issue an occasional warning that it’s all going to end in ruins.

That’s what the World Bank did last week when it joined the BIS (the ‘central banks’ central bank’ is perhaps most notable for the fact that not a single central bank actually listens to its recommendations) in warning that the largest and fastest rise in global debt in half a century could lead to another financial crisis as the world economy slows.

In a report titled “Global Waves of Debt”, the world bank looked at the four major episodes of debt increases that have occurred in more than 100 countries since 1970 — the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s, the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s and the global financial crisis from 2007 to 2009.

While not finding anything the IIF didn’t already point out last month, the bank said during the fourth wave, from 2010 to 2018, the debt to GDP ratio of developing countries has risen by more than half to 168%: that was a faster increase on an annual basis than during the Latin American debt crisis.

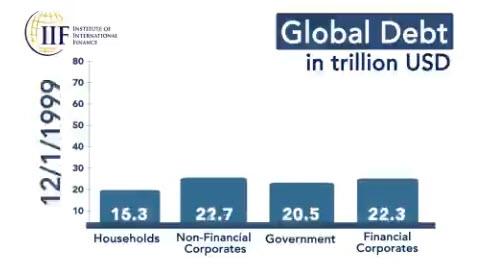

And, as the IIF found previously, the rise in debt has been across both private companies and governments across the world, amplifying the risks if there is another global financial crisis. As a reminder, this is what global debt looked like 20 years ago….

… and what it looks like today:

Something else the World Bank found that we already know: debt growth in the past decade was mostly concentrated in China which accounted for the bulk of the increase, with its debt-to-GDP ratio rising by nearly three-quarters to 255% since 2010, now totaling more than $20 trillion.

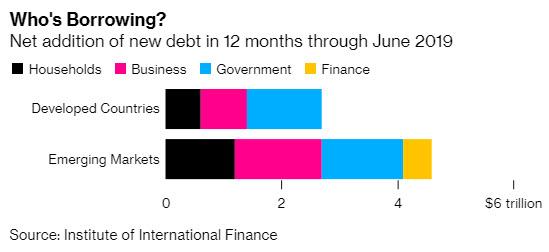

Of course, it’s not just China, as most emerging economies saw their debt rise over the eight years, and especially in the past 12 months.

With common knowledge out of the way, the World Bank report said the latest wave of debt was more challenging than the previous three waves because of the build up of both private and public debt, new types of creditors including foreign investors and the big rise in borrowing, which was global and not limited to one or two regions. Poorer countries have also increasingly borrowed from non-traditional lenders such as China, which offer less favorable loan conditions, including higher interest rates and requiring stakes in projects as collateral, according to ABC .

Trump’s appointee to the World Bank, David Malpass, said governments needed to strengthen their economic policies to make their countries less vulnerable to financial shocks: “It underscores why debt management and transparency need to be top priorities for policymakers — so they can increase growth and investment and ensure that the debt they take on contributes to better development outcomes for the people,” he said.

“The size, speed, and breadth of the latest debt wave should concern us all”, the report noted.

The irony, is that even in its warning, the World Bank failed to isolate the root of the problem: the report said low interest rates globally reduced the risk of a crisis for the time being, which is true; it is also the main factor enabling governments around the world to issue another wave of debt layering even more debt upon debt, and prompting Bloomberg articles explaining how only more debt can “”solve a debt crisis.

Even so, the World Bank’s vice president for equitable growth, finance and institutions Ceyla Pazarbasioglu said the dangers were building up.

“History shows that large debt surges often coincide with financial crises in developing countries, at great cost to the population,” she said.

The report focused on total developed nation debt, which remained near the record levels reached in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, at around 265% of GDP in 2018, or $US130 trillion: “While government debt has risen, to a high of 104 per cent of GDP ($US50 trillion), private sector debt has fallen slightly amid deleveraging in some sectors. Total debt has fallen since 2010 in two-fifths of advanced economies,” the report said.

Of course, none of this is new: the World Bank and the IMF – which on one hand have been enabling the world’s rush into more debt – have paradoxically also been warning for some years about the build up of global debt since the GFC.

Amusingly, according to some analysts, the World Bank report “has upped the pressure on governments to prevent another debt crisis” as it found that of 519 cases of debt surges in 100 emerging and developing countries since 1970 roughly half ended in financial crises.

Malpass called on governments to improve management of their debts to lower borrowing costs and said both governments and creditors needed to be more transparent about loans.

“Emerging and developing economies already are more vulnerable on a variety of fronts than they were ahead of the last crisis,” he said. “75 per cent of them now have budget deficits, their foreign currency denominated corporate debt is significantly higher, and their current account deficits are four times as large as they were in 2007. “Under these circumstances, a sudden rise in risk premiums could precipitate a financial crisis, as has happened many times in the past.”

Which is why central banks can never allow a “sudden rise in risk premiums.”

Which is why interest rates can never be allowed to rise again.

Which is why the can must be kicked at all costs, and why debt growth will only accelerate.

Which is why the “really smart people” will keep repeating the same idiotic drivel until the next crisis finally hits.

Which is why the next crisis may be the last.

Tyler Durden

Sun, 12/22/2019 – 14:40

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/35Oa8CL Tyler Durden