“This Pattern Is Unusual”: Why Morgan Stanley Thinks 2019 Was One Of The Most Bizarre Years Ever

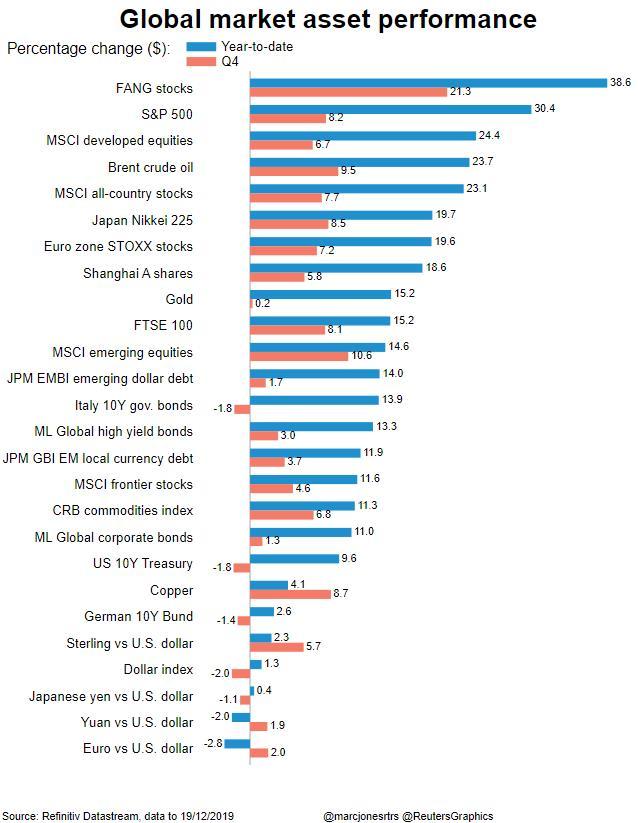

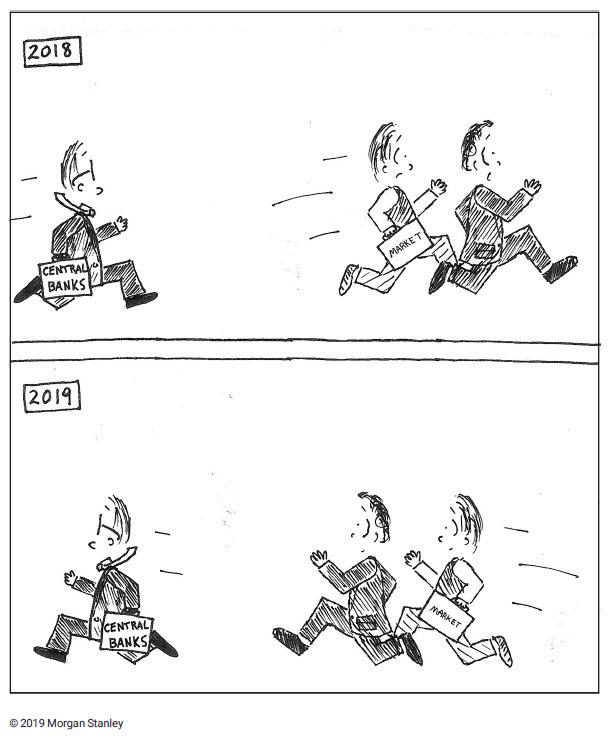

After a dismal 2018, when the worst December since the Great Depression capped a year for markets when not a single asset class managed to beat inflation, 2019 has been a mirror image, and showed that a lot can change with just one phone call and one Fed capitulation.

Indeed, as Morgan Stanley’s cross-asset strategist Andrew Sheets writes in his year-end review, “2019 will go down as one of the strongest years for global stocks in the last thirty” and adds that “as we head into the holidays, a time full of market retrospectives, we except this raw strength to dominate the narrative”, especially with Trump reminding his tens of millions of followers virtually every day that the S&P has hit all time highs at least 135 times since the 2016 election.

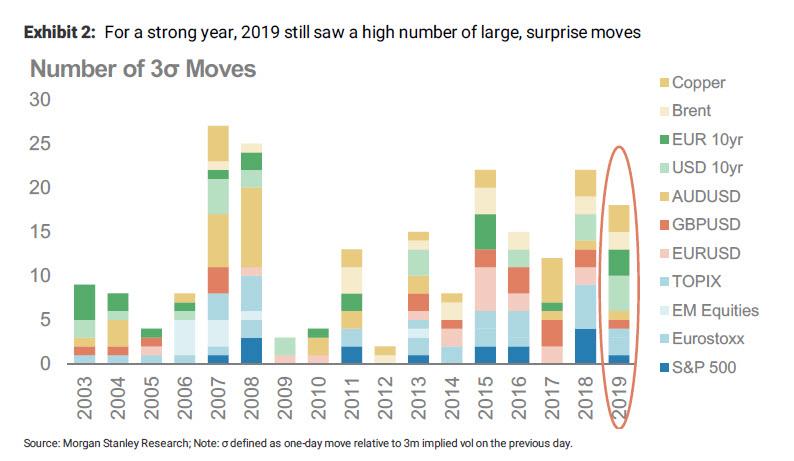

Yet classifying 2019 as simply “strong” is misleading, Sheets explains, noting the year’s gains mask a host of oddities, from the outperformance of defensive assets in a roaring market, to hedge funds getting clobbered and massively underperforming broader equity indexes, to a five-month period that saw no gains for stocks even as interest rates dropped, to an outsized number of 3-sigma moves.

The last point stands in contrast to the false conventional wisdom that 2019 was a “strong, calm, central bank supported year”; instead, 2019 contained quite a few surprises, suggesting underlying liquidity may be more temperamental than currently expected; worse, as Bank of America pointed out last week, “The World’s Most Liquid Stock Market Is Now As Illiquid As It Was In The 2008 Crisis.”

In short, 2019 was one of the most bizarre years ever.

In listing out the ways in which 2019 was a stranger year, Sheets first notes that 2019 was…

The Backwards Year.

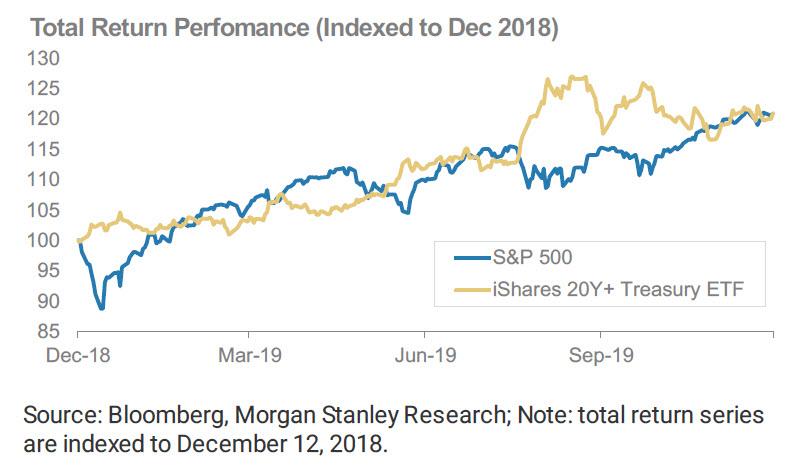

The first oddity of 2019 is that both cautious and aggressive investors will likely claim victory. Bulls, because of huge gains in stocks, credit, and Emerging Market fixed income. Bears, because bonds also rallied sharply, and the “alpha”of much of 2019 was in strategies that work when the world is a difficult place. Consider:

Overall, 20yr+ US Treasuries nearly matched the performance of the S&P 500 for the 12 months leading up to December 12, 2019. Through August of this year, long-dated bonds were significantly outperforming stocks. Well into 2019, allocators could have been underweight equities, overweight duration, and outperformed.

In equities, US large caps outperformed small caps by ~7%, defensives outperformed cyclicals by ~1%, and in Europe, utilities, healthcare and “quality” stocks all outperformed in a market that climbed ~23% overall. In fixed income, US BBs outperformed lower-quality CCCs by ~655bp in excess return (i.e., duration-hedged), and ~740bp in total return. In securitized credit, senior CLO tranches outperformed more junior ones. In Emerging Markets, higher-rated sovereigns are generally tighter relative to recent history than their lower-rated counterparts.

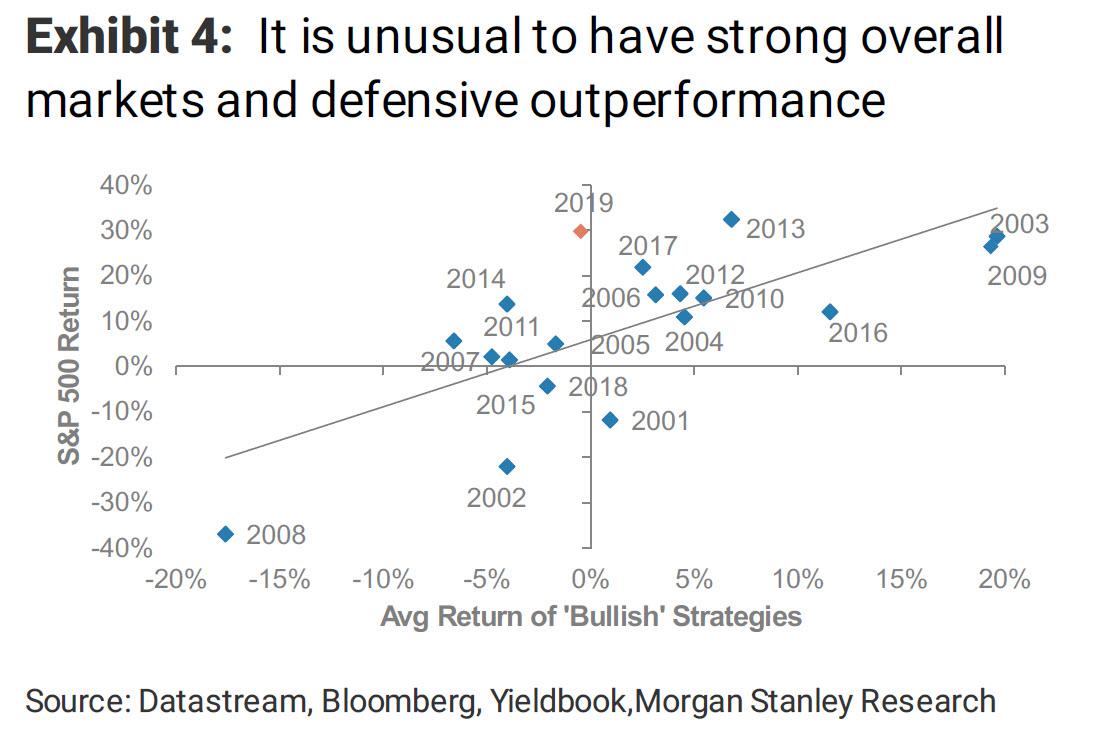

This pattern is, as Morgan Stanley says, unusual. In the next chart, Morgan Stanley shows the annual performance of the S&P 500 against the average of four “bullish” strategies: Cyclical vs. defensive equities, small vs. large cap equities, high yield vs. investment grade (total return), and BBs vs. CCCs (excess return). What happened in 2019, is that despite one of the best returns in the S&P in history, bullish strategies underperformed…

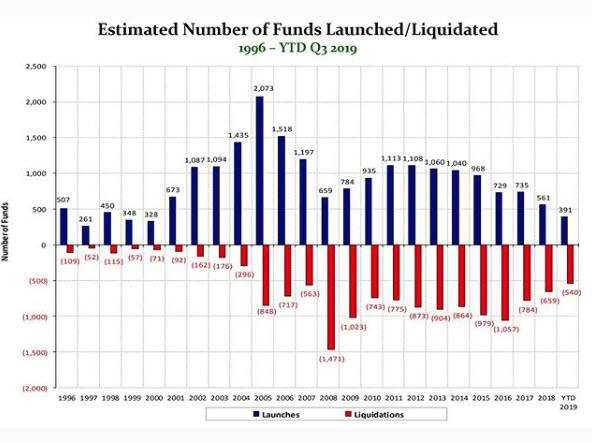

… which whiplashed virtually all hedge funds, resulting in the biggest equity outflows on record, and the fewest hedge fund launches since the start of the Millennium.

Or, as Morgan Stanley politely puts it: “In the last 30 years, there are not many that look like 2019.”

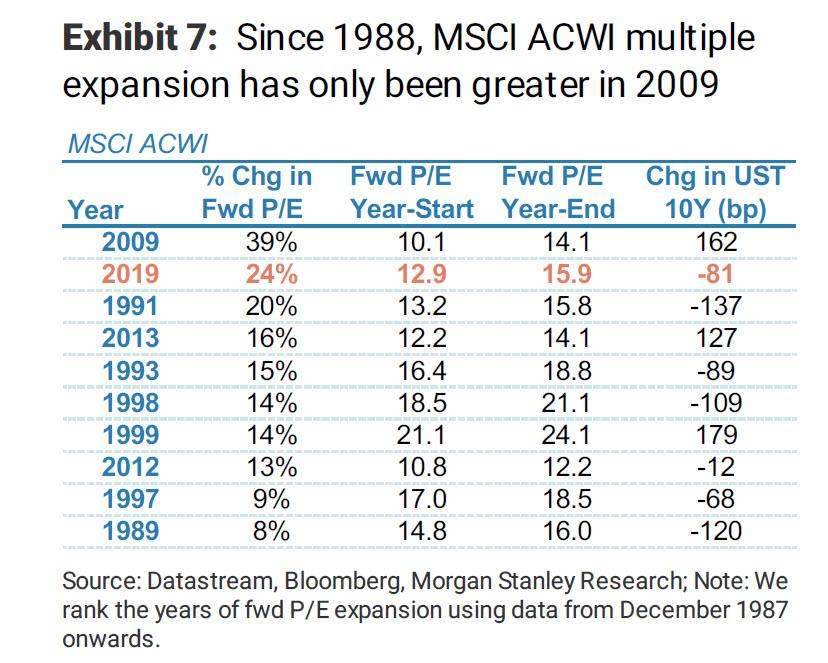

2019 Was Also the Year Of Multiple Expansion

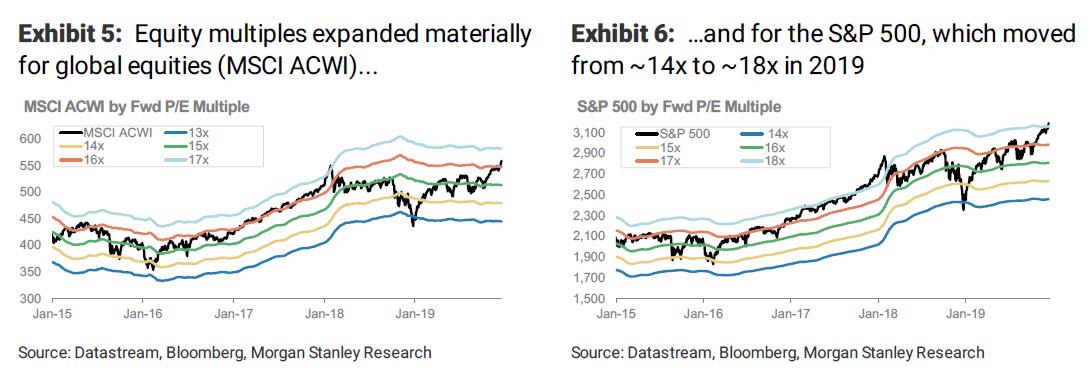

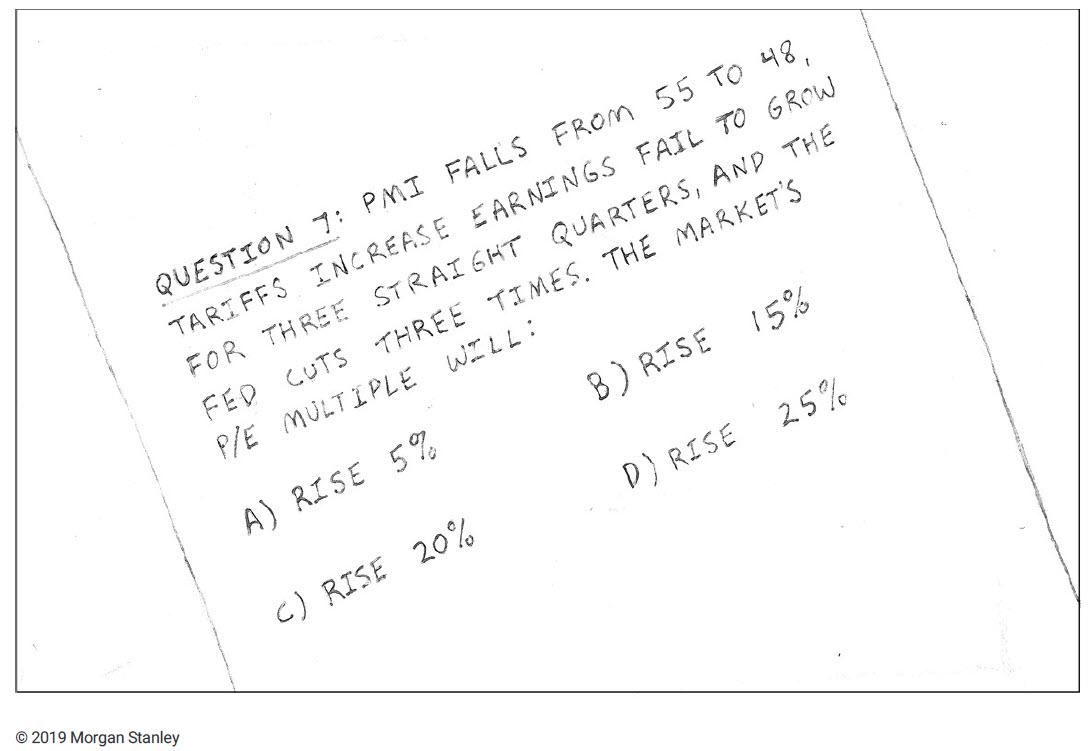

Consider this: in 2019, global corporate earnings were down (both abroad and in the US), yet the MSCI ACWI is up 24% and the S&P500 is up almost 30%. Why? Two words: multiple expansion.

Here are the facts: since January 1, 2019, the forward P/E multiple for global equities (MSCI ACWI) has risen ~24%. That’s despite worsening global PMIs, an outright decline in 2019 earnings, and increases in US-China tariff rates over the time period. For the S&P 500, the multiple also increased ~24%.

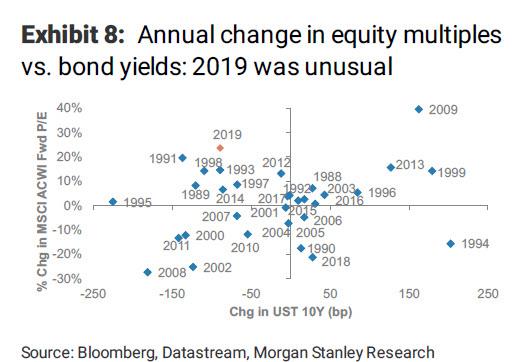

The narrative this year (with more than a little bit of hindsight) has been that these valuation gains were supported by how much yields declined, as the lack of investment alternatives pushed money into stocks. But history shows the risks to this logic. In exhibit 8, Morgan Stanley has plotted the annual change in global equity valuations against the annual change in US 10yr yields. There is little (if no) correlation.

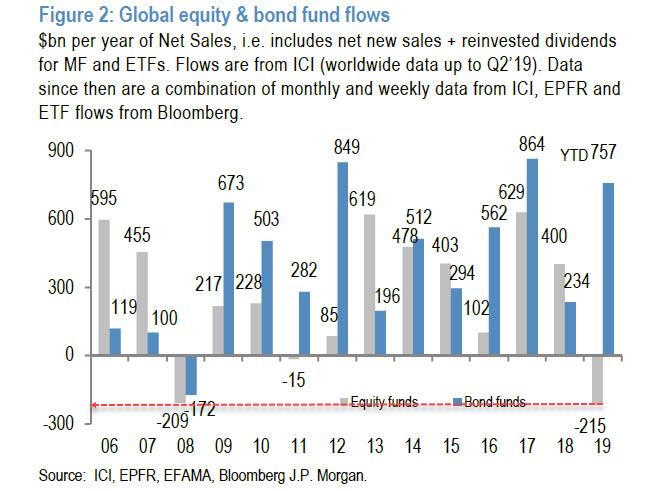

Meanwhile, equity fund flow show that record amounts of money came out of stocks in 2019!

And while the second higher forward PE multiple expansion on record did miracles for stocks in 2019…

… next year will be payback time. As Sheets puts it, “multiple expansion matters because it raises the pressure for companies to deliver on estimates in 2020.”

Which brings us to what has become somewhat of a trademark for Morgan Stanley in recent years: the bank’s unrepentant bearishness. Because while the bank believes that outside the US, “a combination of better macro and micro trends will help earnings for stocks in Korea, Japan, Brazil, Spain and the UK meet or beat expectations, fundamental improvement that can support or even expand current valuations”, for US equities, however, the bank believes that its 0% EPS forecast for 2020 growth “will disappoint expectations, prevent further multiple expansion, and ultimately drive a modest contraction in the multiple, leaving the S&P 500 at ~3,000 by 4Q20.“

* * *

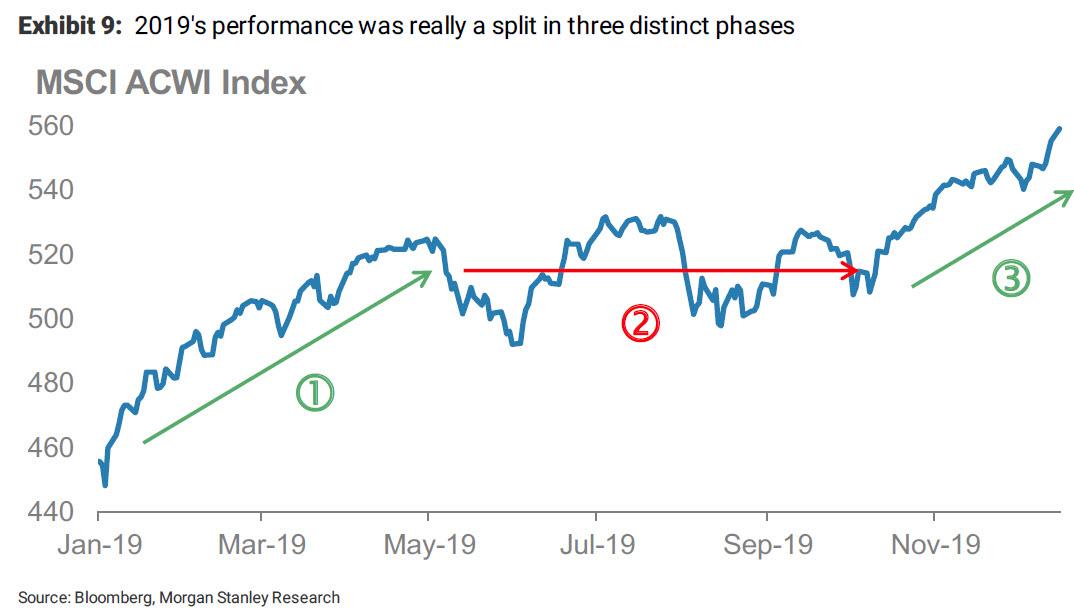

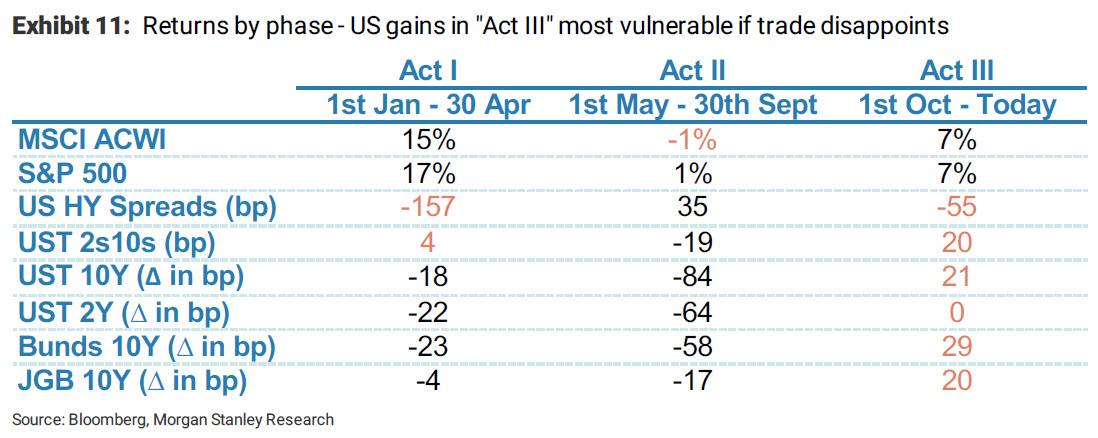

If that’s not enough, another way to look back at 2019, is that it was “a year in three acts”, or as Sheets puts it, there really were three distinct phases. Considering global equities:

- 1. Act I: A powerful rally from depressed valuations and sentiment, as the Federal Reserve made a dramatic reversal to its policy guidance (January 1 – April 30)

- 2. Act II: A volatile period of no gains for five months, as the market worried about a lack of trade progress and continued weakness in global data (May 1 – September 30)

- 3. Act III: A “year end” rally driven by hope that at least ‘phase one’ of the US-China trade deal could be completed, and balance sheet expansion from both the Fed and ECB

Charted, these acts look as follows:

Why are the three acts important?

Because as Morgan Stanley explains, it’s common to hear that equities and credit will be well supported as long as interest rates are low. But “Act II” demonstrates a clear, and very recent, threat to this notion, showing that markets can certainly stall given low rates if earnings growth disappoints and central banks offer little in the way of new policy.

In fact, one can argue that only the “troubles in the repo market” which started in September, and triggered a nearly $400 billion expansion in the Fed’s balance sheet, including the launch of QE4, permitted the recent surge in stocks. More on that later.

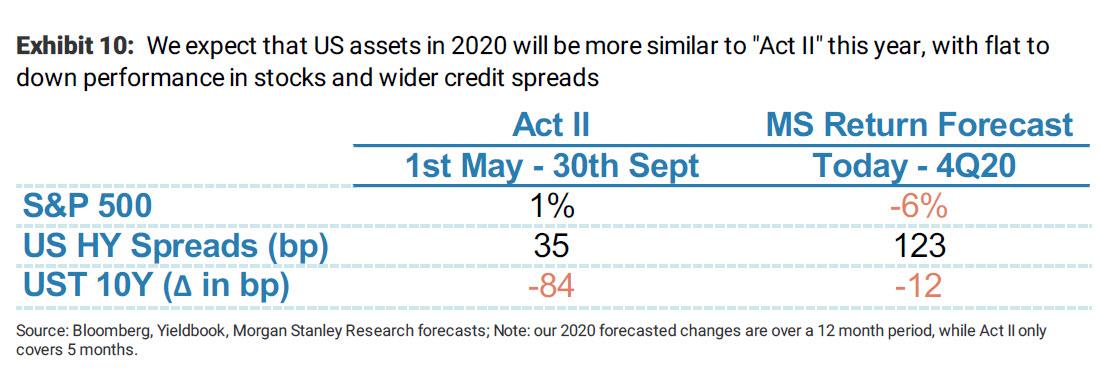

Going back to “Act II”, Morgan Stanley finds ominous similarities between this phase and its own 2020 forecast, in which it sees no S&P 500 earnings growth, no incremental progress on trade after phase one, and no incremental easing measures by G4 central banks (beyond what is already announced).

That sounds a lot like “Act II”, and we note that our forecasts for next year (-6.0% to our year-end S&P 500 target of 3000), credit spreads (+123bp to our year-end high yield target) and range-bound US Treasury yields have some broad similarities to this phase of 2019.

A slightly more optimistic take can be extracted from Act III, which helps quantify risks around trade…: With “Act III” driven in part by increased confidence about a US-China trade deal, Sheets thinks rolling back the performance of “Act III” is a reasonable way to think about levels if trade tensions re-emerge. While the recently announced “phase one” deal was a bit better than the bank’s (if not Goldman’s) expectations, it was a little worse than what the market was expecting, and still contains key unknowns. Importantly, the bank’s Public Policy team remains skeptical about further progress, noting a significantly higher degree of difficulty in the issues that remain.

…and central bank policy: Trade optimism was one driver of the market’s rally since October. Central bank easing was another. The ECB ramped up its bond purchases, but more importantly, the Fed began expanding its balance sheet again to address a perceived shortage in system reserves.

And here is the $64 trillion question: Morgan Stanley expects the Fed to expand its balance sheet through April/May. “After that, markets may once again have to confront a world with limited trade progress and no further Fed support.” As Sheets concludes, “given the importance that markets have assigned to both trade and Fed policy this year, “sell in May and go away” could be very relevant in the year ahead.

One final risk looking ahead, and as hinted by “Act III” is that “reflation” could become “inflation”, as commodity prices have quietly strengthened in the last few weeks, with US breakevens rising, cyclical stocks outperforming, and China PMI rising to about 50.

For now, investors remain skeptical of a sustained rise of G3 inflation, or would welcome it as it would be seen as a sign of better growth and returning normality. Our economic forecasts also have inflation rising in 2020, but central banks effectively embracing that rise with no change in policy. But as Sheets reminds us, “it is not that long ago, in 2018, when markets viewed a rise in inflation as more problematic. In 2019, every asset has rallied. But in 2018, almost every asset declined, and markets began to worry that excess capacity in the global economy was being used up. Inflation is a risk to that we need to watch.” In other words, for all those hoping that reflation emerges in 2020 as a dominant theme, be careful what you wish for – you just may get it…

Tyler Durden

Sun, 12/22/2019 – 17:10

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2PM7Gac Tyler Durden