$180 Billion Asset Manager: “There Is No Way Out, Fed Policies Can No Longer Be Exited Without Provoking The Next Crisis”

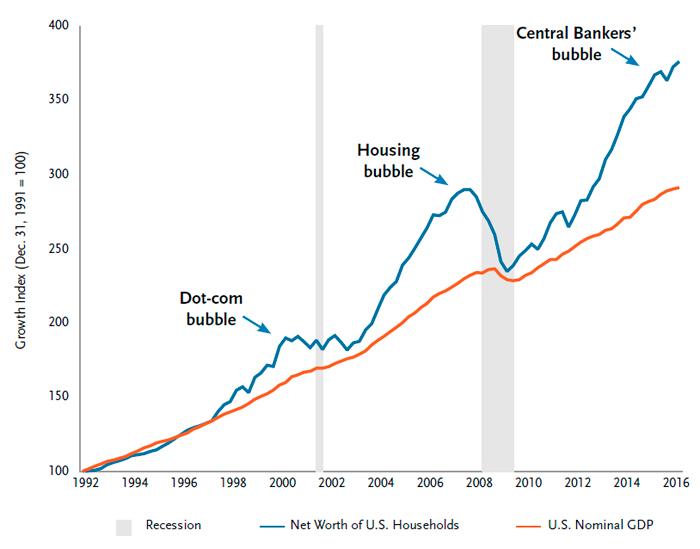

When just over three years ago, TCW’s Chief Investment Officer in Fixed Income, Tad Rivelle, who oversees roughly $180BN in assets, or more than Jeff Gundlach, stated that we are now living through the third consecutive asset bubble in a row, “the central bankers’ bubble” which followed the dot com and housing bubbles…

… he naturally caused a stir as back then he was still one of the first established professionals to confirm and admit that this particular “tinfoil conspiracy theory” website had been right all along: the market’s performance was entirely due to the Fed, and that the longer the Fed’s “emergency” measures continued, the more locked in the central bank would be as the reverse process, namely price discovery without Fed intervention, would result in a catastrophic crisis that could even lead to global war.

A few years later, Tad Rivelle’s then shocking report would have barely registered, as it is now common knowledge that every single market is distorted beyond comprehension due to Fed policies (with a handful of idiots still pretending that’s not true), and while everyone knows that continued central bank intervention will only make the ensuing final crash that much greater, nobody has any idea how to detach the Fed from capital markets.

Which brings us to Rivelle’s latest note, which while far less controversial this time, still manages to hit the nail on the head with punchlines which once again excoriates the “free market” for becoming more centrally planned than the USSR had ever hoped to become.

We urge everyone to read it.

* * *

The Fed Continues to Continue to Pretend

The intended consequences of the last decade’s worth of Fed policies are obvious for all to behold. It is the unintended consequences, those that undermine the sustainability of the current asset price regime that are of most interest here.

In the land that monetary policy forgot, when a worker worked, he received his paycheck, from which he freely consumed. Any surplus – or savings – was added to his pool of “loanable funds” which would then be auctioned out to a willing “bidder,” say a bank, a mutual fund, or a rental income opportunity. But when the 2008 crisis hit, market clearing levels for loanable funds were exorbitant. Credit was priced out of reach for all but the most pristine (prudent) borrowers, asset prices were in free fall, and a financial system that had built an excess of leverage was at risk of implosion.

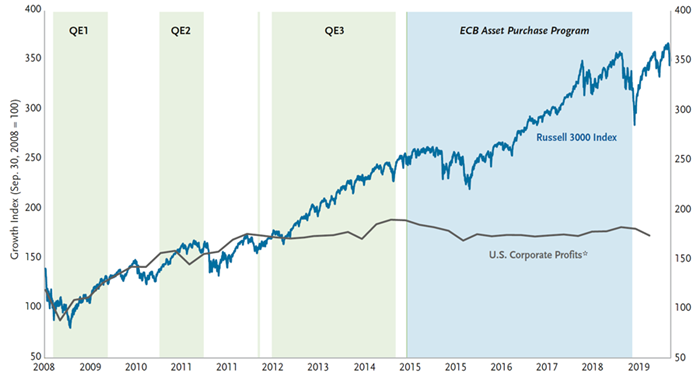

So it was with the best of intentions, the Fed initiated a suite of policies that included QE. Technocratic justifications aside, QE enabled the “printing” of new loanable funds. Unlike the worker who had to provide something of value in exchange for receipt of his loanable funds, the Fed simply conjured new funds from the electronic ether, thereby massively diluting the existing private sector pool of loanable funds. Predictably, bank deposit rates tanked, credit spreads tightened and cap rates were yanked downwards.

Of course, an asset price inflation spurred on by an expansion of credit is exactly what Dr. Bernanke initially ordered up, though you may recall that he never intended the artificial expansion in loanable funds to be a permanent policy. That all changed with the 2013 “taper tantrum” and was reinforced by the 2018 abortive attempt by the Powell Fed to “normalize” rates and balance sheet so slowly that it was supposed to be like watching “paint dry.” Policies implemented as a response to crisis now can’t be exited without provoking the next crisis.

Monetary policies have long since become more problem than solution. This ought not to be such a surprise as the supply side of any economy will invariably configure itself to meet its demand side. And those activities spurred by artificially cheap credit will disappear once that credit is repriced. Raising rates and normalizing the Fed’s balance sheet would now be tantamount to pulling the pegs out from the bottom of the Jenga tower. Fundamentally, you can’t exit a Potemkin economy without forcing changes in the kind and quantities of demand. But, that, of course, would force the supply side to adjust. In other words, we’d have recession.

Exhibit 1: Fed Policies Have Lifted P/E Multiples, Yet Aggregate Profits Have Stagnated

Source: BEA, Bloomberg, IMF, national central banks, TCW

Absent a crisis, faith in the power of monetary tools to foster a healthy configuration of labor and capital has long been severely misplaced. But market forces are powerful precisely because they are rooted in practical realities. Economics is always about the management of scarcity and while expansions in the supply of credit may shift who gets to buy what resources from whom and when, the plain fact is that a scarce commodity remains so regardless of whether interest rates are high or low. While we may be glossing over notions of relative scarcity versus absolute scarcity, an approachable example, say the supply of oceanfront homes, can serve to illustrate the point.

In the example, market forces must necessarily balance the number of people who can buy oceanfront real estate to match the scarcity of oceanfront homes. These constraints can and do, at different times, take the form of high mortgage rates, home price, or loan underwriting standards. And if sales of oceanfront homes were languishing for some reason, the Fed could “stimulate” activity by lowering mortgage rates.

Yet while the Fed can print new loanable funds it can’t add to the supply of oceanfront real estate. So when access to such real estate is no longer limited by say high mortgage rates, home prices will necessarily rise so that a proper rationing mechanism remains in place for the scarce commodity. Indeed, is this not an apt metaphor for what has happened to the price of much U.S. real estate across many metropolitan areas?

While a card carrying Keynesian would point out that rising real estate prices is “obviously” stimulative because higher prices spur such activities as home improvement adding revenue to the construction trades, one has to wonder: an instructive critique of this way of thinking can be found in the entertaining 19th century treatise by Bastiat on the fallacy of the “broken window.” Wherever you might come down on the argument, the basic point is that trying to fool Mr. Market works about as well as trying to fool Mother Nature. If monetary policy were the key to an earthly prosperity, surely all nations would have bootstrapped themselves by the simple artifice of helicopter money.

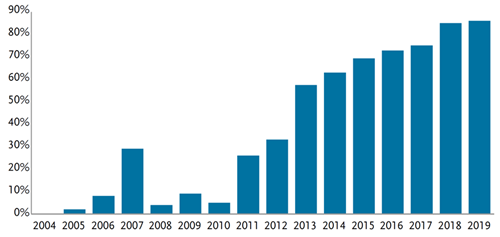

Indeed, rather than igniting an economic boom, cheap and abundant credit have, instead, fostered an elevation in asset prices relative to fundamentals. For instance, enterprise profits for corporate America have gone more or less nowhere for five years (Exhibit 1), but through the magic of share repurchases, higher EPS has helped lift stock prices. In a similar vein, covenant lite loans have enabled private equity to purchase businesses at high multiples all the while retaining an abundance of optionality vis-à-vis the loan/noteholder that has been unprecedented. In short, the right side of the corporate balance sheet can be profoundly altered by central bank policy, but long-term growth is a function of businesses operating more effectively, a reality that shows itself not on the right but rather on the left side of the balance sheet. Operational improvements work best when the incentives to do so are market based – not when credit is artificially cheap.

Exhibit 2: Covenant-Lite Loans As % of All Newly Issued Institutional Loans

And, this brings us full circle to the reality of the past decade: credit binges are always popular because while the benefits of leverage come today, the costs of bad debt come tomorrow. Improving a business or learning a skill requires dedication and hard work. Monetary “stimulus” offers a siren like promise of effortless prosperity yet ignores the reality that credit binges always sow the seeds of their future destruction.

If this sounds a tad abstract, consider September 15 last. On that day, the normally dull as dishwater overnight repo lending rate soared to an astonishing 10% annualized rate. A shocked Fed felt compelled to “do something,” which these days invariably means adding still further to the pool of loanable funds. The size of the add (via the Fed’s T-bill purchases and expansion of its repo facility) has been nearly a cool half-trillion, well over half of the total size of the Fed’s pre-crisis balance sheet. The Fed justified adding this tidal wave of liquidity notwithstanding its characterization that what happened was a mere “technical” glitch in the repo market. Technical, really? A practical take is that the market is talking to the best and brightest minds in central banking, and the Fed doesn’t like what it’s hearing: the repo market wants to clear at rates above the Fed’s IOER fiat rate, which, if allowed to do so, would likely invert the front-end of the yield curve. Inverting curves sounds a bit too much like ending a credit binge, leading to recession, and so the Fed’s response function is to “veto” (Latin for “I forbid”) the market’s signal. Now, who’s fooling whom?

And, so the Fed continues to continue to pretend the cycle need never end. But markets will be what they must be, and investors must face the consequences of the last decade’s credit binge…tomorrow.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 01/23/2020 – 21:45

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2TYj3P3 Tyler Durden