State and local governments hoping for a federal bailout are likely to be on their own for the foreseeable future. Congress failed to reach an agreement this week on another round of coronavirus spending.

After weeks of negotiations over the next coronavirus package, the Senate voted down a so-called “skinny stimulus” bill on Thursday. Sen. Rand Paul (R–Ky.) and Senate Democrats blocked the bill’s advance—though they did so for very different reasons. Paul opposes additional emergency spending because the federal budget deficit is nearing an all-time high, while Democrats want to see yet more spending along the lines of the $3 trillion package the House passed earlier this summer.

Even if it had passed, the Republican-backed $500 billion “skinny stimulus” notably did not include the $1 trillion for cash-strapped states and cities that the House endorsed.

Without that aid on the horizon, some are warning of budgetary catastrophes. The New York Times warned this week of a “dire fiscal crisis” facing some states, declaring in the first paragraph that “Alaska chopped resources for public broadcasting” and that “New York City gutted a nascent composting program that could have kept tons of food waste out of landfills.” Many states have canceled planned pay raises for teachers and other public officials too, the Times notes.

That doesn’t sound like a crisis. It sounds like states are recognizing that falling tax revenue means they will be unable to spend as much as they’d originally planned in the next year or two. In other words, they are doing the important work of budgeting and setting priorities—work that Congress, with its nearly unlimited credit card, refuses to do.

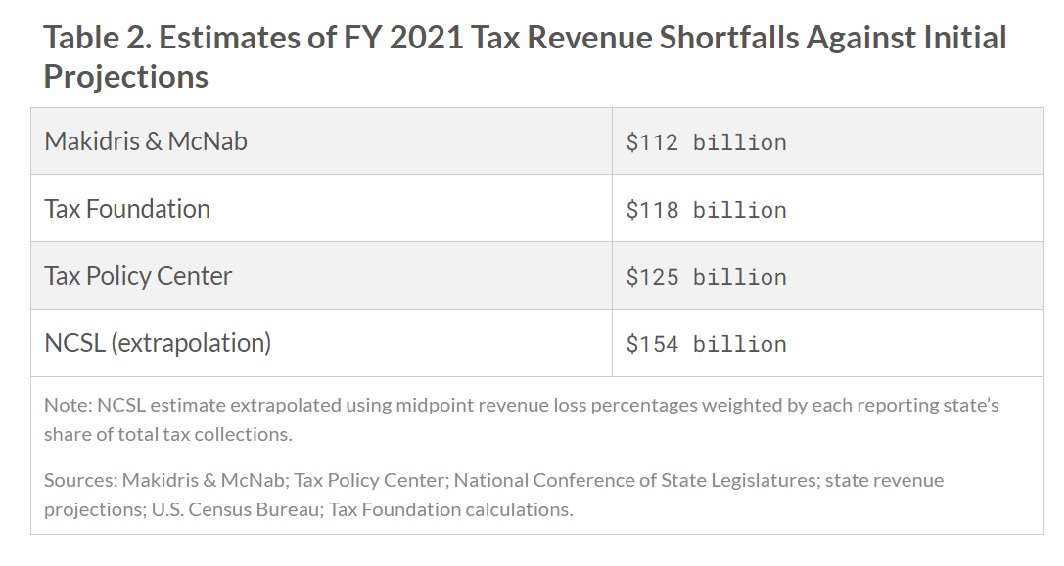

While every state is different, the overall picture for state budgets looks less pessimistic now than it did a few months ago. In April, Moody’s projected that the 50 states were facing a $275 billion revenue shortfall over the next two years due to the coronavirus—and projected that at least 12 states would be able to fully cover their shortfalls with rainy day funds and budgetary reserves. But more recent analyses from a variety of sources—including the Tax Policy Center, the Tax Foundation, and the National Conference of State Legislatures—estimate that the revenue hit will be less severe:

The American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank, published a paper this week estimating that state governments face a $105 billion revenue shortfall. When combined with local governments, the revenue shortfall will be about $240 billion.

Those are big numbers. But as a percentage of state revenues, they hardly represent a dire situation. According to the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO), state revenue for fiscal year 2020 (which in most states ended on June 30) fell by about 3 percent from fiscal year 2019 levels. High unemployment means that state revenue might take a few years to recover, and “many governors and their administrations have directed agencies to develop contingency plans to reduce their budgets, for fiscal year 2021 and/or fiscal year 2022, by as much as 15 or 20 percent,” NASBO reports.

That seems like a prudent thing to do. It is exactly the sort of thing that policy makers should be doing in the face of a public health crisis and economic downturn: reevaluating budgets to prioritize the important things and cutting where possible.

Budget shortfalls can also push state officials to get creative by doing things they probably should have done a while ago. New Mexico and Pennsylvania, for example, are considering legalizing recreational marijuana, so they can tax it to refill their coffers.

“The states face budget challenges, but the situation in most places is not ‘dire,'” writes Chris Edwards, director of tax policy for the Cato Institue, a libertarian think tank. “State officials can solve budget gaps without further federal aid by tapping rainy day funds, freezing hiring and wages, and improving program efficiencies.”

There is little indication, even in the most pessimistic of scenarios, that states need a $1 trillion bailout from the cash-strapped federal government. And a bailout would create a moral hazard, giving states less incentive to address their own budgetary problems in the future.

Deliberately or not, Congress seems to be letting the states figure this out on their own. That’s just fine.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2FcQ5pG

via IFTTT