When Eldridge Cleaver ascended the Marriott Center stage on June 28, 1981, the Black Panther Party wasn’t quite dead. The organization’s last remnants were running an alternative school in Oakland, California, and that final Panther project didn’t peter out until 1982. But Cleaver, who a decade earlier had been head of the party’s International Section in Algeria, didn’t have anything to do with the group anymore. Far from Oakland and even farther from Algiers, he was standing before a sea of neatly dressed Mormons in Provo, Utah, where he spoke for more than an hour about the evils of Communism, the glory of God, and why he wanted the United States to export democracy to the world. Cleaver had once warned that America’s institutions were instilling ugly ideals in its citizens, driving them to the point where that “the shit gets all fucked up and twisted up and you end up in the John Birch Society.” Now the same man was warmly namechecking a prominent Bircher, saying he’d been “running around with Dr. W. Cleon Skousen.”

Cleaver still had harsh words for some of the cops he’d clashed with in the 1960s. But now he had been to the socialist world, and he had come away convinced that the cops there were even worse. “The thing that I used to resent the most about American police, in my own personal experience, was one time the police in San Francisco kicked my door down,” he said. “But I had an experience in Algeria…over there, the police came through the wall.”

It’s a real stemwinder. If you want the historical context for the speech, scroll down. If you want to just jump in and take it straight, here you go:

In the last couple of installments of the Friday A/V Club, we’ve looked at “a disorienting moment in American history: a time after the convulsions of the 1960s and ’70 had ended but while most of the giant figures of that faded age were still around, trying to find a place for themselves in a changed world.” The ex-Panther in Provo was a particularly vivid case.

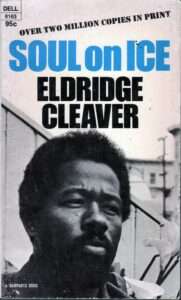

Eldridge Cleaver spent his youth in and out of jails, reformatories, and prisons, his most serious crimes being a series of rapes. Radicalized behind bars, he produced the book that made him famous: Soul on Ice, largely written in prison and then published after his release. It was both a bestseller and one of the central Black Power texts of the ’60s, and it solidified his status as one of the most prominent Black Panthers, rivaled in fame only by party founders Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. But in 1968—barely more than a year after he was paroled from Soledad, not quite two months after Soul on Ice appeared—he got into a shootout with some Oakland cops and fled the country, spending the next seven years in Cuba, Algeria, and France, with side trips to a variety of Communist countries.

Eldridge Cleaver spent his youth in and out of jails, reformatories, and prisons, his most serious crimes being a series of rapes. Radicalized behind bars, he produced the book that made him famous: Soul on Ice, largely written in prison and then published after his release. It was both a bestseller and one of the central Black Power texts of the ’60s, and it solidified his status as one of the most prominent Black Panthers, rivaled in fame only by party founders Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. But in 1968—barely more than a year after he was paroled from Soledad, not quite two months after Soul on Ice appeared—he got into a shootout with some Oakland cops and fled the country, spending the next seven years in Cuba, Algeria, and France, with side trips to a variety of Communist countries.

From his base in Algiers, Cleaver fantasized about global revolution—and had a hand in the birth of the Black Liberation Army, a violent offshoot of the Panthers. But the repression and racism that he saw in the Eastern Bloc reminded Cleaver of the prisons he had lived in back in America, and he grew disillusioned with Communism (though he maintained a soft spot for the North Vietnamese). And then, in France, he found Jesus.

As Cleaver tells it in his 1978 book Soul on Fire—yes, there is a Christian sequel to Soul on Ice called Soul on Fire—the exiled Panther saw a vision in the sky, as shadows on the Moon seemed to form an image of his own face. “As I stared at this image, it changed, and I saw my former heroes paraded before my eyes. Here were Fidel Castro, Mao Tse-tung, Karl Marx, Frederick Engels, passing in review—each one appearing for a moment of time, then dropping out of sight, like fallen heroes. Finally, at the end of the procession, in dazzling, shimmering light, the image of Jesus Christ appeared.” In 1975, the homesick revolutionary returned to the United States, where he spent eight months in jail. But before long he was on the outside again, traveling the evangelical circuit and appearing on TV with the likes of Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, and Jim and Tammy Fae Bakker. Once, when Cleaver saw Falwell debating a gay professor on a Philadelphia TV station, he made his way to the studio and sat in the front row of the audience, telling the announcer that he “thought Brother Jerry needed some help, so I came to give him support.”

Cynics charged Cleaver with opportunism. One Maoist who had known him in the ’60s accused his old comrade of “acting a fool and being dangled to the public by the rulers of this country, spouting this madness about how he saw Jesus in the moon and all the rest of it, when all he saw (probably loaded at the time) was a chance to crawl back on his belly and keep his raggedy ass out of jail.” The Black Panthers’ leader, Elaine Brown, suggested that Cleaver was covertly working for the feds. (Much later, Cleaver’s ex-wife would fling the same charge at Elaine Brown.)

The issue came up even in friendly venues. In a 1977 appearance on the Christian TV show I Believe—hosted by a left-leaning Catholic, not a conservative evangelical—it was the first question the interviewer asked: “Was it a real conversion to the Lord Jesus, or is it just something you imagined out of loneliness and desperate need—a need to return, a need to work out the political and legal hassles?” How do we know you’re sincere?

If you want to be cynical about Cleaver’s motives, you might note that his evangelical period coincided with a significant piece of patronage. It was Arthur DeMoss, a major donor to Falwell’s university and to the Campus Crusade for Christ, who ended Cleaver’s eight-month imprisonment by posting his $100,000 bail, and it was the Campus Crusade for Christ that then sponsored his speaking engagements. When Cleaver started his own ministry, the Eldridge Cleaver Crusades, DeMoss was a major funder. Cleaver’s break with the evangelical mainstream—marked by a speech in which he declared that he “would rather be with the littlest Moonie than with Billy Graham”—came a month after his benefactor died. In a recent article for Religion and American Culture, Dan Wells notes that Cleaver sometimes expressed reservations about the role he found himself playing, complaining in his private journal that he felt Jim and Tammy Fae Bakker were using him as a “token.”

Yet to me it seems clear that Cleaver’s conversion was sincere. You can see that in the very fact that he had trouble being contained by a stereotypical evangelical identity—that rather than simply following the script his new fan base expected, he made it a step in a spiritual path that was hard to take as anything but sincere, given how eccentric it was. “I’ve done a lot of shopping in the theological supermarket,” he told that interviewer in 1977. That shopping trip continued for the rest of his life.

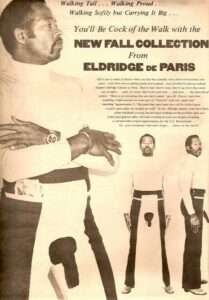

In 1979 he got involved with Project Volunteer, an Oakland front group for the Rev. Sun Myung Moon’s Unification Church, though it wasn’t completely clear how he felt about Moon’s religion. (In contemporaneous profiles for New West and the Berkeley Barb—the latter teased on the cover as “Cleaver’s Moon Trip“—he gave the impression that he liked Project Volunteer’s charitable work but was trying to get members out of the church; each article reported that he had been working on an anti-Moonie book titled Divine Deception. The book never appeared.) In 1980, Cleaver—who had gone through a Nation of Islam period in San Quentin and who had spent much of his evangelical period reaching out to disillusioned Black Muslims—announced that he would be launching his own religion, a fusion of Christian, Muslim, and uniquely Cleaverite doctrines that he called “Christlam.” (Among other things, the fledgling faith held that “the dwelling place of God” is “in the male sperm.” Cleaver was fixated on semen and the organ that produced it: When the man who introduced his Provo talk mentioned that the old Panther had been working in clothing design, he refrained from noting that Cleaver’s most notable contribution to fashion was a line of pants featuring a codpiece designed to stop the practice of “penis binding.”)

In 1979 he got involved with Project Volunteer, an Oakland front group for the Rev. Sun Myung Moon’s Unification Church, though it wasn’t completely clear how he felt about Moon’s religion. (In contemporaneous profiles for New West and the Berkeley Barb—the latter teased on the cover as “Cleaver’s Moon Trip“—he gave the impression that he liked Project Volunteer’s charitable work but was trying to get members out of the church; each article reported that he had been working on an anti-Moonie book titled Divine Deception. The book never appeared.) In 1980, Cleaver—who had gone through a Nation of Islam period in San Quentin and who had spent much of his evangelical period reaching out to disillusioned Black Muslims—announced that he would be launching his own religion, a fusion of Christian, Muslim, and uniquely Cleaverite doctrines that he called “Christlam.” (Among other things, the fledgling faith held that “the dwelling place of God” is “in the male sperm.” Cleaver was fixated on semen and the organ that produced it: When the man who introduced his Provo talk mentioned that the old Panther had been working in clothing design, he refrained from noting that Cleaver’s most notable contribution to fashion was a line of pants featuring a codpiece designed to stop the practice of “penis binding.”)

And then he found the Mormons.

The most complete account I’ve seen of Cleaver’s Mormon period is “Eldridge Cleaver’s Passage Through Mormonism,” a paper published by Newell G. Bringhurst in the Spring 2002 Journal of Mormon History. According to Bringhurst, Cleaver’s first “direct contact” with the Latter-day Saints came in late 1980, when a former New Left comrade suggested he look into the church. At this point the Mormons did not have a reputation as a welcoming place for African Americans—they did not start ordaining black priests until 1978. But Cleaver apparently felt welcome as he met with Skousen, Ezra Taft Benson, and others in 1981, and soon he was giving talks under the aegis of Skousen’s Freeman Institute. (Now called the National Center for Constitutional Studies, the organization has been a notable influence on the conservative broadcaster Glenn Beck.) I’m not sure if Cleaver ever read Skousen’s classic conspiracy tract, The Naked Communist, or its more baroque sequel, The Naked Capitalist. But he was impressed by the writings of Joseph Smith, and also by Smith’s 1844 presidential campaign, which ended with a mob murdering the candidate in jail.

By this time, Cleaver had plea-bargained his way out of serving any more jail time for the Oakland shootout. But he was still on parole, and he was barred from being baptized into the church until that was completed. Eventually it was, and Cleaver became a Mormon in 1983.

That same year, he told the Associated Press that he was open to the idea of resurrecting the Black Panther Party. One wonders what that would have looked like. Cleaver had written to Bobby Seale in 1982, acknowledging that he had “move[d] in a different ideological direction” but suggesting they still could work together. “The capitalistic system is in a state of general crisis and black people are being sacrificed on the altar of national recovery,” he wrote. “The police department are preying upon the people and are poised to crush them. The very food supply of the people is in jeopardy. There is no organized force to represent the people. We can—and must create such a force.”

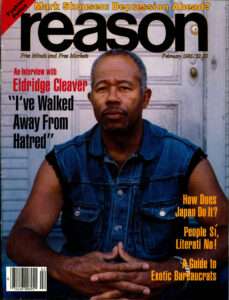

The ’80s Cleaver made a few unsuccessful bids for office, with platforms that sounded conventionally conservative—he criticized Communism and the welfare state, praised private enterprise and Ronald Reagan—until he got to the issue of drugs: On that matter, he told CBS during his 1986 run for the Senate, “I think we should decriminalize them, and take the enormous profit out of the illicit trade.” When Reason interviewed Cleaver around the same time, he reiterated the argument in earthier terms: “the same way that we got J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI out of Prohibition, we’re getting what I call the Piss Police out of this whole drug situation. It’s absolutely catastrophic in terms of our freedom.” (When Cleaver took an unpoliced bathroom break, one of Reason‘s interviewers, Bill Kauffman, stole a glance at Cleaver’s files. The two he remembers were labeled “Sperm” and something along the lines of “Jim Morrison: Alive?”)

The ’80s Cleaver made a few unsuccessful bids for office, with platforms that sounded conventionally conservative—he criticized Communism and the welfare state, praised private enterprise and Ronald Reagan—until he got to the issue of drugs: On that matter, he told CBS during his 1986 run for the Senate, “I think we should decriminalize them, and take the enormous profit out of the illicit trade.” When Reason interviewed Cleaver around the same time, he reiterated the argument in earthier terms: “the same way that we got J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI out of Prohibition, we’re getting what I call the Piss Police out of this whole drug situation. It’s absolutely catastrophic in terms of our freedom.” (When Cleaver took an unpoliced bathroom break, one of Reason‘s interviewers, Bill Kauffman, stole a glance at Cleaver’s files. The two he remembers were labeled “Sperm” and something along the lines of “Jim Morrison: Alive?”)

Cleaver had his troubles in the ’80s and ’90s. There were financial problems. His marriage split up. For a while he was addicted to crack, and at one low point he pleaded no contest to a misdemeanor burglary charge. He stayed on the Mormon membership rolls through it all, though he attended church less often as time went by.

And then everything seemed to come full circle: In the wake of the Waco standoff, Cleaver’s quirky “right-wing” views seemed to pulsate with the same revolutionary energy as his old “left-wing” ideas. “Through long, personal, bitter experience with the government’s agencies and methods of repression, I recognized early on that the government was systematically poisoning and prejudicing public opinion with a blitz of inflammatory disinformation to stir up hatred against David Koresh and to foment a thirst for his blood,” he wrote. He called the government’s raid an “arrogant, abusive, fascist exercise of state power”—and, in a bit of over-the-top rhetoric that rivaled the fieriest flourishes of his Panther days, he declared: “Nothing done by Hitler’s murderous hordes was worse.”

With the Cold War over and Communism apparently dead, Cleaver was turning back toward his old antiwar politics too. He wrote an essay, left unpublished at the time, that denounced the first Gulf War (and, in a passing reference, returned to condemning Reagan). Interviewed by Henry Louis Gates a year before his death, he defended the Panthers’ legacy while reiterating his criticisms of Marxism. He also told Gates that Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, and the Kennedys had been “killed by the powers that rule this country who did not want to see the political dynasty of the Kennedys take control.”

And he made a late-life move toward feminism—not a decision you’d expect from a man who had once been a serial rapist, who had been physically abusive toward his wife, and who had once gone looking for God in the human sperm. Cleaver expressed these views in a 1995 letter to the psychedelic psychologist Timothy Leary, a man he had put under “revolutionary arrest” when they were both in exile in Algeria. (The two had buried the hatchet when they found themselves in the same California prison, where by Leary’s account they became a “high-scoring two-man basketball team.”) Now Cleaver was urging Leary to hold a joint press conference to “call upon the Democratic Party and the Republican Party both to nominate a woman candidate for president in the year 2000.” The Cleaver-Leary platform, he added, should be centered around “the Loving Heart of a Mother.” It wasn’t your standard feminist rhetoric, and it’s interesting that he envisioned two men making the announcement. But it was another turn in a life that was full of turns, turns that somehow added up to a single whole.

Eldridge Cleaver died in 1998. His son Maceo has become a Muslim, and in 2006 he wrote a book called Soul on Islam. His daughter Joju married Geronimo Pratt, a Black Panther who had spent 27 years in prison before his conviction was overturned. You can see both Maceo and Joju in that video of the speech in Provo, neither of them a teenager yet, sitting behind one of their father’s incarnations as he addresses the assembled Mormons.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3usQQ1T

via IFTTT