Beijing’s Big Tech Crackdown Causes Private Deal Flow To Dry Up In August

Just when market watchers think they’ve seen the last headline about China’s ongoing Big Tech crackdown, Beijing finds some new industry to harass. On Monday, it was the video game industry, as Chinese regulators limited online gaming to just 3 hours per week for minors, while requiring companies to use facial recognition technology and verified accounts to ensure nobody skirts the new rules.

The results have been pretty stark: more than $1 trillion has been wiped off the aggregate market capitalization of Chinese domestic markets, along with China-based companies traded in Hong Kong and the US.

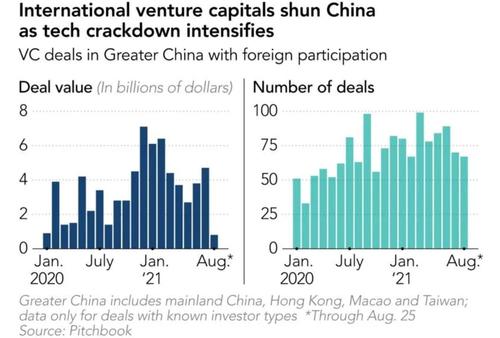

But it’s not just the public markets that are feeling the impact. Foreign investors have backed away from financing Chinese startups, as the number and value of private equity deals involving foreign investors has fallen in August to its lowest monthly level since the start of the pandemic.

According to Nikkei, which cited the latest figures from data firm PitchBook, deal flow was set to surpass levels from 2020 – until funding suddenly dried up in August.

Chinese startups have raised $32.6 billion from 634 deals that included foreign VCs this year as of Aug. 25, compared with $18.9 billion from 453 in the first eight months of 2020. So far in August, however, just $800 million has been raised from 67 deals with foreign participation, down from $4.7 billion in July.

What else happened around then? The answer should be obvious to most China watchers: Didi’s ill-fated IPO took place at the end of June. With several days remaining in August, $800 million would be a new low, beating the previous low for the pandemic period – $900 million from January 2020 – by $100 million. But even before the Didi IPO, China’s crackdown on its biggest tech firms was already becoming an issue.

Chinese VCs have also scaled back their deal flow in August, though not as dramatically. The value of all deals signed in the country so far this month is $6.6 billion, down from around $9 billion in each of June and July.

The sudden evaporation of deal flow has certainly gotten the investing community’s attention, but at the end of the day, China is simply too large of a market for PE firms to ignore. So few expect it to last long.

Jeffrey Lee, a partner at China-focused venture capital firm NLVC headquartered in Beijing, said robotics and manufacturing automation has been an increasingly hot sector. While more caution and strategy shifts are warranted, exiting China entirely would be out of the question, he said.

“The hard reality is that you can’t find a replacement for the sheer size of the economy, the next phase of its growth and — despite all of the criticism toward the government — the level of institutional development, whether it’s in roads or bridges, or whether it’s in the banking system,” Lee said. “It just doesn’t exist anywhere else in the world.”

VC interest in consumer-focused businesses that are bearing the brunt of Beijing’s crackdown now is also unlikely to shrivel entirely.

“Ultimately there are a lot of consumers in China, and a lot of rising middle-class consumers who are willing to spend,” said Joshua Chao, senior analyst at PitchBook. “There’s a strong reason to say that consumer businesses are still gonna do pretty well in China.”

But the lessons investors have learned about the unique political risks that arise from investing in China will likely linger on. And from here on out, while most expect Chinese firms will continue to go public abroad, Hong Kong will likely replace New York as the preferred venue. That means lower valuations, especially for giant loss-making tech firms with stellar top-line growth.

That could pull down equivalent private valuations, and there could be a further impact if companies are ultimately steered away from going public via New York’s deep capital markets, toward Shanghai, Shenzhen or Hong Kong.

“I think there will still be a resumption of overseas IPOs, but that will probably mean, most likely Hong Kong, and not New York,” said Lee.

Hong Kong’s institutional and retail investors are less keen to back loss-making consumer companies with big long-term ambitions, he said.

“The best thing about the New York markets was that you could take a company that is generating loss but with great top-line growth and build a narrative that created a very successful public company. That is, with few exceptions, not the case in Hong Kong.”

This means valuations might take time to recover.

Tyler Durden

Mon, 08/30/2021 – 19:20

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3gHa9jp Tyler Durden