Sidney Homer’s Odyssey

By Michael Every of Rabobank

Bonds were battered again yesterday, the US 10-year closing up 10bps at 4.53%, a new cycle high. “4% or 5% next?”, many are asking. To understand that odyssey, it’s time to dip into Homer.

I don’t mean reading the classics (“Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns”). I don’t mean watching modern classics like The Simpsons (“Lisa, if you don’t like your job, you don’t strike. You just go in every day and do it really half-assed. That’s the American way.”) I am referring to an epic tome on my bookshelf for nearly 20 years: Sidney Homer’s ‘A History of Interest Rates’.

One recent take was that the US 10-year Treasury yield at 4.50% is back to the long-run average… if one takes data back to 1790, when most analysts think looking back to 1970 is long-term. The argument was that the yield high was hence probably now in – and then it rose again. Yes, history is a good guide – but only if you have enough of it. Believe it or not, 1790 is not that far back.

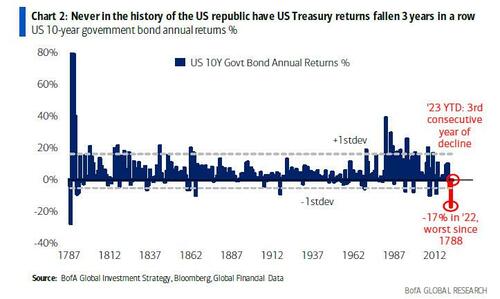

For example, we are likely to see a third consecutive loss in US Treasuries in 2023, which has never happened since US independence. Most would therefore have told you that it ‘could not happen’; history is laughing at the bond bulls who are crying.

That’s partly because (Sidney) Homer makes the case for how unprecedentedly low rates during the New Normal were: the lowest for 5,000 years, or all of recorded history. It made some sense at the time, but the lowest rates in history **for the rest of history** was only logical if, Fukuyama fashion, history was over, and nothing forced rates higher again. But instead we got:

- Populist Western governments. One US poll now has Trump up over Biden 52% – 42% for 2024. Likewise, the FT shows growing up with low GDP growth makes one think in zero- not positive-sum terms, so the New Normal was self-destroying; and another op-ed underlines economic modellers now argue a 35% US tariff on Chinese goods would create 7.3m new jobs, and increase household income by 17.6%. What was once anathema is now algebra.

- A global virus killing millions and invaliding up to 2% of the labor force, as the Covid ‘Batwoman’ warns new viruses are inevitable (some say ‘the election variant’ is).

- Ultra-tight labour markets, where Austrian metalworkers want an 11.6% pay rise, the striking US UAW have support from both the president and his leading 2024 rival, overall strikes are at a 20-year high, the Wall Street Journal underlines ‘Why America has a Long-Term Labour Crisis, in Six Charts’, and ‘Hollywood Studios, Writers Reach Pact, Haggle on Language’(!), the latter getting what they call an “exceptional” deal with “meaningful gains”.

- A major war in Europe that will drag on for years, with concerns over other flashpoints.

- Supply destruction, as Nord Stream was blown up, and restrictions were placed on exports from rice to semiconductors. Russia just halted diesel exports, the lifeblood of the physical economy, pushing it’s price up again: France’s Macron may ask firms to sell diesel at cost in response, but slashing their profits and keeping demand for fuel high while supply is constrained won’t work.

- Global South ‘dedollarisation’, to little effect so far, but maximum disruption if it does.

- Geopolitical fragmentation of global supply chains, with more to come.

- Ocean carrier giant Maersk dropping US military contracts to invest more in China. This underlines that the US needs to rebuild its own merchant marine rapidly, and so its shipyards, and so its steel industry, etc., or else end up in very, very ‘Deep Ship’. How else will the US military move stuff around if foreign-owned civilian ships won’t do it?

As the WSJ’s Nick Timiraos quotes Powell at last week’s Fed press conference, “There is a long list,” and even the FOMC’s dovish Goolsbee was hawkish yesterday for those reasons.

Notably, RaboResearch predicted most of this global backdrop years ago. Perhaps we were too early – but better that than too late. Perhaps we were just lucky – or maybe an historical political-economy methodology (i.e., like this) worked. Regardless, today you don’t need as much chutzpah to look at diesel, politics, geopolitics, demographics, deglobalisation, debt levels, the green transition, and massive bond supply ahead as structural factors arguing for the risk of higher rates and bond yields than in the recent past.

Indeed, our Fed-watcher Philip Marey sees the floor in Fed Funds as no lower than 3.5%, lifting short-end bond yields. Further down the curve, the ‘term premia’ is now actually minus 9bp, and looking over the past five years, one could argue it can go down again, moving longer yields lower. However, history back to the 1990s –the 1790s not being available, sadly– shows said term premia have most often been positive, not negative, and as high as 450bp(!)

This doesn’t mean bond yields can’t tumble: they could. However, what an odyssey lies ahead of us if so! That would imply a collapse in inflation, despite structural upside pressures from geopolitics and energy; that would imply a collapse in demand via a surge in unemployment – in a US, UK, and Canadian election year; and governments refusing to spend money to fight it (or to boost defence, or the green transition) – in an election year. It would also imply a quick resolution of US- and EU-China trade tensions, just as Europe is echoing Le Trumpism over EVs, and Trump is saying ‘mercantilism’.

Then again, a collapse in bond yields might imply a financial crisis. However, in the US we’ve already seen the preference –again as RaboResearch flagged in advance– is for rate hikes and acronyms (like BTFP) to tighten and loosen policy at the same time. So, it might then imply a crisis in the Eurodollar market that dwarfs the US banking system. Are we close to the tipping point in the ratio between the on- and off-shore dollar markets, and the geopolitical threshold towards dedollarisation, after which the Fed says “We aren’t saving everyone”? That would bring commodities and inflation down fast – and a lot else with it!

Geopolitically, that all smells like ‘volatility’, to put it mildly. But very volatile periods are also there in Homer. Whether it is the first Cold War; the Vietnam, or Korean Wars; WW2 or WW1; the wars of late European imperialism; the US Civil War; the Reformation and the Wars of Religion; the Middle Ages and the 100-Years War; the rise and fall of the Roman Empire (yes, I am thinking about it now!); or the waxing and waning of the Middle Eastern empires before it – none had long-term rates as low as those we saw from 2008-2020.

In short, just as many say we are not replaying 1970’s yield highs –and I agree, we aren’t– so very long-run bond history does not suggest that 2008-2020 is necessarily a realistic benchmark to look back to today given structural changes of late.

Yet given not everyone agrees, we must embrace a broader variety of Homeric wisdom:

“Our earth is degenerate in these latter days; bribery and corruption are common; children no longer obey their parents; every man wants to write a book, and the end of the world is evidently approaching.” – S. Homer (from an Assyrian tablet, when short-term rates were around 20%)

“Ah how shameless — the way these mortals blame the gods. From us alone, they say, come all their miseries, yes, but they themselves, with their own reckless ways, compound their pains beyond their proper share.” – Homer (when Greek short-term rates were around 10%)

“Apu, if it makes you feel any better, I’ve learned that life is just one crushing defeat after another until you just wish Flanders was dead.” – Homer S. (when US short-term rates were 7.70% and long-term rates 7.80%)

Tyler Durden

Tue, 09/26/2023 – 10:15

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/Hngum5c Tyler Durden