Authored by Nafeez Ahmed via Medium.com,

For some, the crisis in Venezuela is all about the endemic corruption of Nicolás Maduro, continuing the broken legacy of Chavez’s ideological experiment in socialism under the mounting insidious influence of Putin. For others, it’s all about the ongoing counter-democratic meddling of the United States, which has for years wanted to bring Venezuela – with its huge oil reserves -back into the orbit of American power, and is now interfering again to undermine a democratically elected leader in Latin America.

Neither side truly understands the real driving force behind the collapse of Venezuela: we have moved into the twilight of the Age of Oil.

So how does a country like Venezuela with the largest reserves of crude oil in the world end up incapable of developing them? While various elements of socialism, corruption and neoliberal capitalism are all implicated in various ways, what no one’s talking about — especially the global oil industry — is that over the last decade, we’ve shifted into a new era. The world has moved from largely extracting cheap, easy crude, to becoming increasingly dependent on unconventional forms of oil and gas that are much more difficult and expensive to produce.

Oil isn’t running out, in fact, it’s everywhere — we’ve more than enough to fry the planet. But as the easy, cheap stuff has plateaued, production costs have soared. And as a consequence the most expensive oil to produce has become increasingly unprofitable.

In a country like Venezuela, emerging from a history of US interference, plagued by internal economic mismanagement, combined with external intensifying pressure from US sanctions, this decline in profitability became fatal.

Since Hugo Chavez’s election in 1999, the US has continued to explore numerous ways to interfere in and undermine his socialist government. This is consistent with the track record of US overt and covert interventionism across Latin America, which has sought to overthrow democratically elected governments which undermine US interests in the region, supported right-wing autocratic regimes, and funded, trained and armed far-right death squads complicit in wantonly massacring hundreds of thousands of people.

Protestors clash with police in Caracas

For all the triumphant moralising in parts of the Western media about the failures of Venezuela’s socialist experiment, there has been little reflection on the role of this horrific counter-democratic US foreign policy in paving the way for a populist hunger for nationalist and independent alternatives to US-backed cronyism.

Before Chavez

Venezuela used to be a dream US ally, model free-market economy, and a major oil producer. With the largest reserves of crude oil in the world, the conventional narrative is that its current implosion can only be due to colossal mismanagement of its domestic resources.

Described back in 1990 by the New York Times as “one of Latin America’s oldest and most stable democracies”, the newspaper of record predicted that, thanks to the geopolitical volatility of the Middle East, Venezuela “is poised to play a newly prominent role in the United States energy scene well into the 1990’s”. At the time, Venezuelan oil production was helping to “offset the shortage caused by the embargo of oil from Iraq and Kuwait” amidst higher oil prices triggered by the simmering conflict.

But the NYT had camouflaged a deepening economic crisis. As noted by leading expert on Latin America, Javier Corrales, in ReVista: Harvard Review of Latin America, Venezuela had never recovered from currency and debt crises it had experienced in the 1980s. Economic chaos continued well into the 1990s, just as the Times had celebrated the market economy’s friendship with the US, explained Corrales: “Inflation remained indomitable and among the highest in the region, economic growth continued to be volatile and oil-dependent, growth per capita stagnated, unemployment rates surged, and public sector deficits endured despite continuous spending cutbacks.”

Prior to the ascension of Chavez, the entrenched party-political system so applauded by the US, and courted by international institutions like the IMF, was essentially crumbling. “According to a recent report by Data Information Resources to the Venezuelan-American Chamber of Commerce, in the last 25 years the share of household income spent on food has shot up to 72 percent, from 28 percent,” lamented the New York Times in 1996. “The middle class has shrunk by a third. An estimated 53 percent of jobs are now classified as ‘informal’ — in the underground economy — as compared with 33 percent in the late 1970’s”.

The NYT piece cynically put all the blame for the deepening crisis on “government largesse” and interventionism in the economy. But even here, within the subtext the paper acknowledged a historical backdrop of consistent IMF-backed austerity measures. According to the NYT, even the ostensibly anti-austerity president Rafael Caldera — who had promised more “state-financed populism” as an antidote to years of IMF-wrought austerity — ended up “negotiating for a $3 billion loan from the IMF” along with “a second loan of undisclosed size to ease the social impact of any hardships imposed by an IMF agreement.”

So it is convenient that today’s loud and self-righteous moral denunciations of Maduro ignore the instrumental role played by US efforts to impose market fundamentalism in wreaking economic and social havoc across Venezuelan society. Of course, outside the fanatical echo chambers of the Trump White House and the likes of the New York Times, the devastating impact of US-backed World Bank and IMF austerity measures is well-documented among serious economists.

In a paper for the London School of Economics, development economist Professor Jonathan DiJohn of the UN Research Institute for Social Development found that US-backed economic “liberalisation not only failed to revive private investment and economic growth, but also contributed to a worsening of the factorial distribution of income, which contributed to growing polarisation of politics.”

Neoliberal reforms further compounded already existing centralised nepotistic political structures vulnerable to corruption. Far from strengthening the state, they led to a collapse in the state’s regulative power. Analysts who hark back to a Venezuelan free market golden age ignore the fact that far from reducing corruption, “financial deregulation, large-scale privatisations, and private monopolies create[d] large rents, and thus rent-seeking/corruption opportunities.”

Instead of leading to meaningful economic reforms, neoliberalisation stymied genuine reform and entrenched elite power. And this is precisely how the West helped create the Chavez it loves to hate. In the words of Corrales in the Harvard Review:

“… economic collapse and party system collapse — are intimately related. Venezuela’s repeated failure to reform its economy made existing politicians increasingly unpopular, who in turn responded by privileging populist policies over real reforms. The result was a vicious cycle of economic and political party decay, ultimately paving the way for the rise of Chavez.”

Dead oil

While it is now fashionable to blame the collapse of the Venezuelan oil industry solely on Chavez’s socialism, Caldera’s privatisation of the oil sector was unable to forestall the decline in oil production, which peaked in 1997 at around 3.5 million barrels a day. By 1999, Chavez’s first actual year in office, production had already dropped dramatically by around 30 percent.

A deeper look reveals that the causes of Venezuela’s oil problems are slightly more complicated than the ‘Chávez killed it’ meme. Since peaking around 1997, Venezuelan oil production has declined over the last two decades, but in recent years has experienced a precipitous fall. There can be little doubt that serious mismanagement in the oil industry has played a role in this decline. However, there is a fundamental driver other than mismanagement which the press has consistently ignored in reporting on Venezuala’s current crisis: the increasingly fraught economics of oil.

The vast bulk of Venezuela’s oil is not conventional crude, but unconventional “heavy oil”, a highly viscous liquid that requires unconventional techniques to extract and flow, often with heat from steam, and/or mixing it with lighter forms of crude in the refining process. Heavy oil thus has a higher cost of extraction than normal crude, and a lower market price due to the refining difficulties. In theory, heavy oil can be produced at below break-even prices to a profit, but greater investment is still needed to get to that point.

The higher costs of extraction and refining have played a key role in making Venezuela’s oil production efforts increasingly unprofitable and unsustainable. When oil prices were at their height between 2005 and 2008, Venezuela was able to weather the inefficiencies and mismanagement in its oil industry due to much higher profits thanks to prices between $100 and $150 a barrel. Global oil prices were spiking as global conventional crude oil production began to plateau, causing an increasing shift to unconventional sources.

That global shift did not mean that oil was running out, but that we were moving deeper into dependence on more difficult and expensive forms of unconventional oil and gas. The shift can be best understood through the concept of Energy Return on Investment (EROI), pioneered principally by the State University of New York environmental scientist Professor Charles Hall, a ratio which measures how much energy is used to extract a particular quantity of energy from any resource. Hall has shown that as we are consuming ever larger quantities of energy, we are using more and more energy to do so, leaving less ‘surplus energy’ at the end to underpin social and economic activity.

This creates a counter-intuitive dynamic — even as production soars, the quality of the energy we are producing declines, its costs are higher, industry profits are squeezed, and the surplus available to sustain continued economic growth dwindles. As the surplus energy available to sustain economic growth is squeezed, in real terms the biophysical capacity of the economy to continue buying the very oil being produced reduces. Economic recession (partly induced by the previous era of oil price spikes) interacts with the lack of affordability of oil, leading the market price to collapse.

That in turn renders the most expensive unconventional oil and gas projects potentially unprofitable, unless they can find ways to cover their losses through external subsidies of some kind, such as government grants or extended lines of credit. And this is the key difference between Venezuela and countries like the US and Canada, where extremely low EROI levels for production have been sustained largely through massive multi-billion dollar loans — fuelling an energy boom that is likely to come to a catastrophic end when the debt-turkey comes home to roost.

“It’s all a bit reminiscent of the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s, when internet companies were valued on the number of eyeballs they attracted, not on the profits they were likely to make,” wroteBethany McLean recently (once again in the New York Times), a US journalist well-known for her work on the Enron collapse. “As long as investors were willing to believe that profits were coming, it all worked — until it didn’t.”

A number of scientists have previously estimated the EROI of heavy oil production to amount to around 9:1 (with room for variation up or down depending on how inputs are accounted for and calculated; the unfashionable but probably more accurate approach would be downwards, closer to 6:1 when both direct and indirect energy costs are considered). Compare this to the EROI of about 20:1 for conventional crude prior to 2000, which gives an indication of the challenge Venezuela faced — which unlike the US and Canada, had emerged into the Chavez era from a history of neoliberal devastation and debt-expansion that already made further investments or subsidies to Venezuela’s oil industry a difficult ask.

Venezuela, in that sense, was ill-prepared to adapt to the post-2014 oil price collapse, compared to its wealthier, Western competitors in other forms of unconventional oil and gas. To be sure, then, the collapse of Venezuela’s oil industry cannot be reduced to geological factors, though there can be little doubt that those factors and their economic ramifications tend to be underplayed in conventional explanations. Above-ground factors were clearly a major problem in terms of chronic inadequacy of investment and the resulting degradation of production infrastructure. A balanced picture thus has to acknowledge both that Venezuela’s vast reserves are far more expensive and difficult to bring to market than standard conventional oil; and that Venezuala’s very specific economic circumstances in the wake of decades of failed IMF-austerity put the country in an extremely weak position to keep its oil show on the road.

Since 2008, oil production has declined by more than 350,000 barrels per day, and more than 800,000 per day since its peak level in 1997. This has driven the collapse of net exports by over 1.1 million barrels per day since 1998. Meanwhile, to sustain refining of heavy oil, Venezuela has increasingly imported light oil to blend with heavy oil as well as for domestic consumption. Currently, only extra-heavy oil production in the Orinoco Oil Belt has been able to increase, while conventional oil production continues to rapidly decline. Despite significant proved conventional reserves, these still require more expensive enhanced recovery techniques and infrastructure investments — which are unavailable. But profit margins from exports of extra-heavy crude are much smaller due to the higher costs of blending, upgrading and transportation, and the heavy discounts in international refining markets. In summary, oil industry expert Professor Francisco Monaldi at the Center for Energy and the Environment at IESA in Venezuela concludes:

“…. oil production in Venezuela is comprised of increasingly heavier oil and thus less profitable, PDVSA’s operated production is falling more rapidly, and the production that generates cash-flow is almost half of the total production. These trends were problematic enough at peak oil prices, but with prices falling they become much more acute.”

The folly of endless growth

Unfortunately, much like his predecessors, Chavez didn’t appreciate the complexities, let alone the biophysical economics, of the oil industry. Rather, he saw it simplistically through the short-term lens of his own ideological socialist experiment.

From 1998 until his death in 2013, Chavez’s application of what he called ‘socialism’ to the oil industry succeeded in reducing poverty from 55 to 34 percent, helped 1.5 million adults become literate, and delivered healthcare to 70 percent of the population with Cuban doctors. All this apparent progress was enabled by oil revenues. But it was an unsustainable pipe-dream.

Instead of investing oil revenues back into production, Chavez spent them away on his social programmes during the heyday of the oil price spikes, with no thought to the industry he was drawing from — and in the mistaken belief that prices would stay high. By the time prices collapsed due to the global shift to difficult oil described earlier — reducing Venezuala’s state revenues (96 percent of which come from oil) — Chavez had no currency reserves to fall back on.

Chavez had thus dramatically compounded the legacy of problems he had been left with. He had mimicked the same mistake made by the West before 2008, pursuing a path of ‘progress’ based on an unsustainable consumption of resources, fuelled by debt, and bound to come crashing down.

So when he ran out of oil money, he did what governments effectively did worldwide after the 2008 financial crash through quantitative easing: he simply printed money.

The immediate impact was to drive up inflation. He simultaneously fixed the exchange rate to dollars, hiked up the minimum wage, while forcing prices of staple goods like bread to stay low. This of course turned businesses selling such staple goods or involved at every chain in their production into unprofitable enterprises, which could no longer afford to pay their own employees due to haemorrhaging income levels. Meanwhile, he slashed subsidies to farmers and other industries, while imposing quotas on them to maintain production. Instead of producing the desired result, many businesses ended up selling their goods on the black market in an attempt to make a profit.

As the economic crisis escalated, and as oil production declined, Chavez pinned his hopes on the potential transformation that could be ushered in by massive state investment in a new type of economy based on nationalised, self or cooperatively managed industries. Those investments, too, had little results. Dr Asa Cusack, an expert on Venezuela at the London School of Economics, points outthat “even though the number of cooperatives exploded, in practice they were often as inefficient, corrupt, nepotistic, and exploitative as the private sector that they were supposed to displace.”

Meanwhile, with its currency reserves depleted, the government has had to slash imports by over 65 percent since 2012, while simultaneously reducing social spending to even lower than it was under IMF austerity reforms in the 1990s. Chavistan crisis-driven ‘socialism’ began with unsustainable social spending and has now switched to catastrophic levels of austerity that make neoliberalism look timid.

In this context, the rise of the black market and organised crime, exploited by both the government and the opposition, became a way of life while the economy, food production, health-care and basic infrastructure collapsed with frightening speed and ferocity.

Climate wild cards

Amidst this perfect storm, the wild card of climate impacts pushed Venezuela over the edge, accelerating an already dizzying spiral of crises. In March 2018, on the back of hyperinflation and recession, the government enforced electricity rationing across six western states. In one state, San Cristobal, residents reported 14-hour stretches without power after water levels in reservoirs used for hydroelectric plants were reduced due to drought. A similar crisis had erupted two years earlier when water levels behind the Guri Dam, which provides well over half the country’s electricity, hit record lows.

Venezuela generates around 65 percent of its electricity from hydropower, with a view to leave as much oil available as possible for export. But this has made electricity supplies increasingly vulnerable to droughts induced by climate change impacts.

It is well known that the El-Nino Southern Oscillation, the biggest fluctuation in the earth’s climate system comprising a cycle of warm and cold sea-surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific Ocean, is increasing in frequency and intensity due to climate change. A new study on the impact of climate change in Venezuela finds that between 1950 and 2004, 12 out of 15 El-Nino events coincided with years in which “mean annual flow” of water in the Caroni River basin, affecting the Guri reservoir and hydroelectric power, was “smaller than the historical mean.”

From 2013 to 2016, an intensified El-Nino cycle meant that there was little rain in Venezuela, culminating in a crippling deficit in 2015. It was the worst drought in almost half a century in the country, severely straining the country’s aging and poorly managed energy grid, resulting in rolling blackouts.

According to Professor Juan Carlos Sanchez, a co-recipient of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize for his work with Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), these trends will dramatically deteriorateunder a business as usual scenario. Large areas of Venezuelan states which are already water scarce, such as Falcon, Sucre, Lara and Zulia, including the north of the Guajira peninsula, will undergo desertification. Land degradation and decreased rainfall would devastate production of corn, black beans and plantains across much of the country. Sanchez predicts that some regions of the country will receive 25 percent less water than today. And that means even less electricity. By mid-century, climate models indicate an overall 18 percent decrease in rainfall in the Caroni River basin that leads to the Guri Dam.

Unfortunately, no Venezuelan government has ever taken seriously its climate pledges, preferring to escalate as much as possible its oil production, and even intensifying the CO2 intensive practice of gas flaring. Meanwhile, escalating climate change is set to exacerbate Venezuela’s electricity blackouts, infrastructure collapse and agricultural crisis.

Economic war

The crisis convergence unfolding in Venezuela gives us a window into what can happen when a post-oil future is foisted upon you. As domestic energy supplies dwindle, the state’s capacity to function recedes in unprecedented ways, opening the way for state-failure. As the state collapses, new smaller centres of power emerge, competing for control of diminishing resources.

In this context, reports of food-trafficking as a mechanism of ‘economic war’ are real, but they are not exclusive to either political side. All sides have become incentivised to horde products and sell them on the black market as a direct result of the collapsing economy, retrograde government price controls and wildly speculative prices.

Venezuelan state-owned media have pinpointed cases where private companies engaged in hoarding have close ties to the opposition. In response, the government has appropriated vast assets, farmland, bakeries, other businesses — but has failed to lift production.

On the other hand, Katiuska Rodriguez, a journalist investigating shortages at El Nacional, a pro-opposition newspaper, said that there is little clear evidence of hoarding being a result of an ‘economic war’ by capitalist business elites against the government. Although real, she explained, hoarding is driven largely by commercial interests in survival.

And yet, there is mounting evidence that the Maduro government is complicit in not just hoarding, but mass embezzlement of public funds. Sociologist Chris Carlson of the City University of New York Graduate Center points out that a number of former senior Chavista government officials have come on record to confirm how powerful elites within the government have exploited the crisis to extract huge profits for themselves. “A gang was created that was only interested in getting their hands on the oil revenue,” said Hector Navarro, former Chavista minister and socialist party leader. Similarly, Chavez’s former finance minister, Jorge Giordani, estimated that some $300 billion was embezzled in this way.

And yet, the real economic war is not really going on inside Venezuela. It has been conducted by the US against Venezuela, through a draconian sanctions regime which has exacerbated the arc of collapse. Francisco Rodriguez, Chief Economist at Torino Economics in New York, points out that a major drop in Venezuela’s production numbers occurred precisely “at the time at which the United States decided to impose financial sanctions on Venezuela.”

He argues that: “Advocates of sanctions on Venezuela claim that these target the Maduro regime but do not affect the Venezuelan people. If the sanctions regime can be linked to the deterioration of the country’s export capacity and to its consequent import and growth collapse, then this claim is clearly wrong.” Rodriguez marshals a range of evidence suggesting this might well be the case.

Others with direct expertise have gone further. Former UN special rapporteur to Venezuela, Alfred de Zayas, who finished his term at the UN in March 2018, criticised the US for engaging in “economic warfare” against Venezuela. On his fact-finding mission to the country in late 2017, he confirmed the role of overdependence on oil, poor governance and corruption, but blamed the US, EU and Canadian sanctions for worsening the economic crisis and “killing” Venezuelans.

US goals are fairly transparent. In an interview with FOX News that has been completely ignored by the press, Trump’s National Security Advisor John Bolton explained the focus of US attention: “We’re looking at the oil assets. That’s the single most important income stream to the government of Venezuela. We’re looking at what to do to that.” He continued:

“… we’re in conversation with major American companies now… I think we’re trying to get to the same end result here… It will make a big difference to the United States economically if we could have American oil companies really invest in and produce the oil capabilities in Venezuela.”

The coming oil crisis

It is not entirely surprising that Bolton is particularly eager at this time to extend US energy companies into Venezuela.

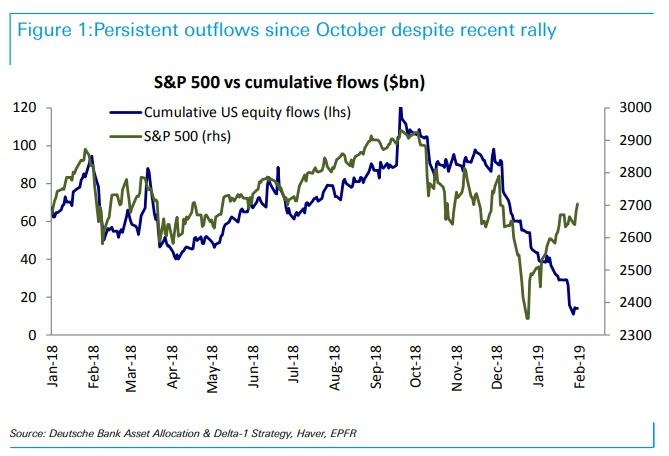

North American exploration and production companies have seen their net debt balloon from $50 billion in 2005 to nearly $200 billion by 2015. “[The fracking] industry doesn’t make money…. It’s on much shakier financial footing than most people realize,” said McLean, who has just authored the book, Saudi America: The Truth About Fracking and How It’s Changing the World. Indeed, there is serious gulf between oil industry claims about opportunities for profit, and what is actually happening in those companies:

“When you look at oil companies’ presentations, there’s something that doesn’t make sense because they show their investors these beautiful investor decks with gorgeous slides indicating that they will produce an 80% or 60% internal rate of return. And then you go to the corporate level and you see that the company isn’t making money, and you wonder what happened between point A and point B.”

In short, cheap debt-money has permitted the industry to grow — but how long that can continue is an open question. “Part of the point in writing my book was just to make people aware that as we trump at American energy independence, let’s think about some of the foundation of this [industry] and how insecure it actually is, so that we’re also planning for the future in different ways”, adds McLean.

Indeed, US shale oil and gas production is forecast to peak in around a decade — or in as little as four years. It’s not just the US. Europe as a continent is already well into the post-peak phase, and Russian oil ministry officials privately anticipate an imminent peak within the next few years. As China, India and other Asian powers experience further demand growth, everyone will be looking increasingly for a viable energy supply, whether from the Middle East or Latin America. But it won’t come cheap, or easy. And it won’t be healthy for the planet.

Whatever their ultimate causes, the horrifying collapse of Venezuela heralds insights into a possible future for today’s major oil producers — including the United States. The US is enjoying a revival in its oil industry but how long it will last and how sustainable it is are awkward questions that few pundits dare to ask — except a brave few, such as McLean.

This does not necessarily mean oil production will simply slowly grind to a halt. As production limits are reached using current techniques, new techniques might be brought into play to try to mine vast reserves of more difficult resources. However, whatever technological innovations emerge they are unlikely to be able to avert the trajectory of increasing costs of extraction, refining and processing before getting fossil fuels to market. And this means that the surplus energy available to devote to the delivery of public goods familiar to modern industrial consumerist societies will become smaller and smaller.

Meanwhile, the environmental consequences of fossil fuel dependency are making investors re-think the financial viability of these industries, creating a growing risk that they become stranded assets. In this emerging future, the trajectory of endless economic growth as we know it cannot continue. Either way, the warnings signs are unmistakeable. As we shift into a post-carbon era, we will have to adapt new economic thinking, and restructure our ways of life from the ground up.

Right now the Venezuelan people find themselves locked into a vicious cycle of ill-conceived human systems collapsing into violent in-fighting, in the face of the earth system crisis erupting beneath them. It is not yet too late for the rest of the world to learn a lesson. We can either be dragged into a world after oil kicking and screaming, or we can roll up our sleeves and walk there in a manner of our own choosing. It really is up to us. Venezuela should function as a warning sign as to what can happen when we bury our heads in the (oil) sands.

* * *

Published by INSURGE INTELLIGENCE, a crowdfunded investigative journalism project for people and planet. Please support us to keep digging where others fear to tread.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2tcz592 Tyler Durden