Bloomberg may be in hot water for scuttling an article that “might anger China” as exposed over the weekend, but that was only after winning investigative prizes for its series of reports exposing the epic wealth of China top ruling families in 2012: a topic that has received prominence at a time when the forced wealth redistribution plans of developed and developing nations, usually originated by these same uber-wealthy families, is all the rage. Another country, whose oligarchic wealth had largely escaped press scrutiny, was Iran. At least until today, when in a six month investigation culminating in a three-part report on the assets of the Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Reuters exposed Setad, an Iranian company that manages and sells property on order from the Imam.

In a nutshell, the company has built up its wealth by seizing thousands of properties from Iranian citizens. According to the investigation, Setad’s assets are worth $95 billion – 40 percent more than Iran’s total 2012 oil exports. It is this confiscated “wealth” that has allowed the Iranian clergy, and especially the Ayatollah, to preserve their power over the years.

In a little more than a nutshell, Reuters explains just who Setad is:

Pari Vahdat-e-Hagh ultimately lost her property. It was taken by an organization that is controlled by the most powerful man in Iran: Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. She now lives alone in a cramped, three-room apartment in Europe, thousands of miles from Tehran.

The Persian name of the organization that hounded her for years is “Setad Ejraiye Farmane Hazrate Emam” – Headquarters for Executing the Order of the Imam. The name refers to an edict signed by the Islamic Republic’s first leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, shortly before his death in 1989. His order spawned a new entity to manage and sell properties abandoned in the chaotic years after the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Setad has become one of the most powerful organizations in Iran, though many Iranians, and the wider world, know very little about it. In the past six years, it has morphed into a business juggernaut that now holds stakes in nearly every sector of Iranian industry, including finance, oil, telecommunications, the production of birth-control pills and even ostrich farming.

The organization’s total worth is difficult to pinpoint because of the secrecy of its accounts. But Setad’s holdings of real estate, corporate stakes and other assets total about $95 billion, Reuters has calculated. That estimate is based on an analysis of statements by Setad officials, data from the Tehran Stock Exchange and company websites, and information from the U.S. Treasury Department.

Just one person controls that economic empire – Khamenei. As Iran’s top cleric, he has the final say on all governmental matters. His purview includes his nation’s controversial nuclear program, which was the subject of intense negotiations between Iranian and international diplomats in Geneva that ended Sunday without an agreement. It is Khamenei who will set Iran’s course in the nuclear talks and other recent efforts by the new president, Hassan Rouhani, to improve relations with Washington.

Unlike developed nations, where the first priority of the super rich is to flaunt their wealth, Iran’s supreme leader lives a spartan lifestyle and has not been found to abuse the massive monetary holdings of Setad. However, as Reuters points out, “Setad has empowered him. Through Setad, Khamenei has at his disposal financial resources whose value rivals the holdings of the shah, the Western-backed monarch who was overthrown in 1979.”

Logically, the next question is just how did Setad accumulate its vast asset holdings. The answer, just as logically, is simple: confiscation.

How Setad came into those assets also mirrors how the deposed monarchy obtained much of its fortune – by confiscating real estate. A six-month Reuters investigation has found that Setad built its empire on the systematic seizure of thousands of properties belonging to ordinary Iranians: members of religious minorities like Vahdat-e-Hagh, who is Baha’i, as well as Shi’ite Muslims, business people and Iranians living abroad.

Setad has amassed a giant portfolio of real estate by claiming in Iranian courts, sometimes falsely, that the properties are abandoned. The organization now holds a court-ordered monopoly on taking property in the name of the supreme leader, and regularly sells the seized properties at auction or seeks to extract payments from the original owners.

Just like in the US where the 1% effectively have molded the status quo into a wealth preservation mechanism, with profound control over not only the capital markets and the regulatory framework but over all three branches of government (simply note how many bankers have gone to prison for the systemic crash of 2008), so in Iran the Ayatollah has shaped society in a way that will ultimately benefit first and foremost him, as well as not only preserve his wealth but facilitate even greater accumulation of confiscated assets under any and all pretexts.

The supreme leader also oversaw the creation of a body of legal rulings and executive orders that enabled and safeguarded Setad’s asset acquisitions. “No supervisory organization can question its property,” said Naghi Mahmoudi, an Iranian lawyer who left Iran in 2010 and now lives in Germany.

Khamenei’s grip on Iran’s politics and its military forces has been apparent for years. The investigation into Setad shows that there is a third dimension to his power: economic might. The revenue stream generated by Setad helps explain why Khamenei has not only held on for 24 years but also in some ways has more control than even his revered predecessor. Setad gives him the financial means to operate independently of parliament and the national budget, insulating him from Iran’s messy factional infighting.

Like every usurpation of power and wealth, Setad’s beginnings were humble and, to an extent, noble.

When Khomeini, the first supreme leader, set in motion the creation of Setad, it was only supposed to manage and sell properties “without owners” and direct much of the proceeds to charity. Setad was to use the funds to assist war veterans, war widows “and the downtrodden.” According to one of its co-founders, Setad was to operate for no more than two years.

Setad has built schools, roads and health clinics, and provided electricity and water in rural and impoverished areas. It has assisted entrepreneurs in development projects. But philanthropy is just a small part of Setad’s overall operations.

One can probably imagine that the founders of the Fed also had noble intentions. Instead they created a dormant century-old monster, intervening in the economy to preserve the wealth of the American financial oligarchy, and whose wealth-transfer capaci

ty has only emerged on the scene in the past five years. So it is not surprising that as absolute power corrupts absolutely, so it is in Iran as it is in the US:

Under Khamenei’s control, Setad began acquiring property for itself, and kept much of the funds rather than simply redistributing them. With those revenues, the organization also helps to fund the ultimate seat of power in Iran, the Beite Rahbar, or Leader’s House, according to a former Setad employee and other people familiar with the matter. The first supreme leader, Khomeini, had a small staff. To run the country today, Khamenei employs about 500 people in his administrative offices, many recruited from the military and security services.

The full Reuters article, the first of three, has much more detail on the asset holdings of the Setad, on its expropriation strategies, on the cover up to hide the full extent of the organization’s involvement in society, and much more, however the broad strokes will be largely familiar to those acquainted with the tactics of any and every oligarch – be they clergical, political or financial – when preservation of power through wealth and money (and confiscation thereof) is the only prerogative.

And while Iran’s wealth confiscation scheme may be extreme by Western standards, at least it is a honest daylight robbery, but what’s worse is that it pales in comparison to what goes on every month not in some enclave of despotic banana republicanism, but the US itself.

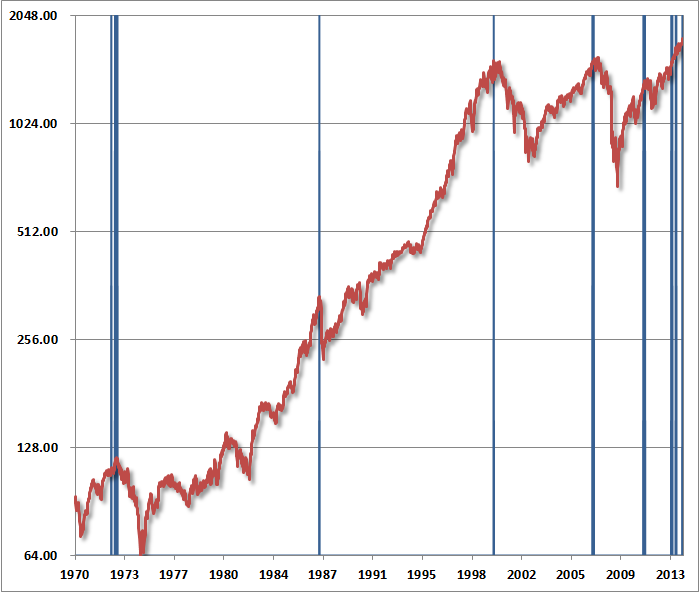

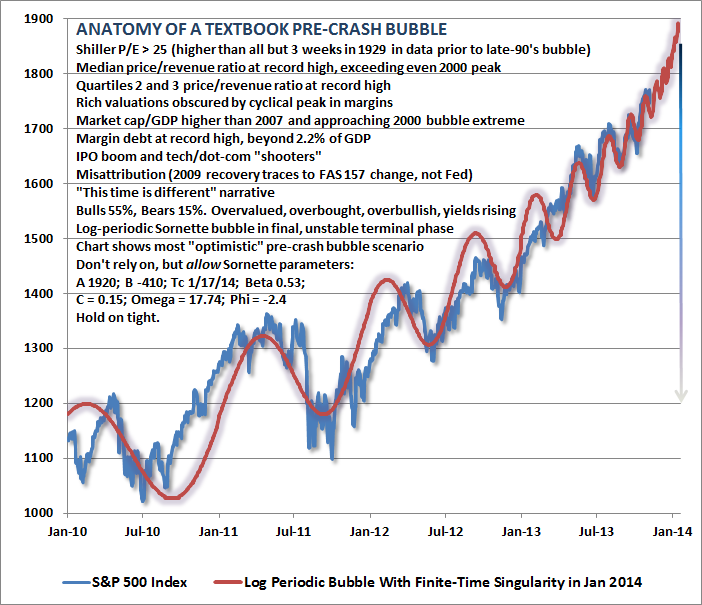

Because putting Setad’s $95 billion in estimated assets in context, these amount to just over 5 weeks of the Fed’s QE, which for those who are not worried about losing their “access journalistic” credentials and are willing to call a spade a spade, is merely asset confiscation and wealth transfer of the most insidious type: one where those whose assets are handed over to the wealthy, are oblivious of what has just happened and are in fact grateful for the privilege of having been robbed under the auspices of the “fairness doctrine” and for the pursuit of the “greater good.”

![]()

via Zero Hedge http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/zerohedge/feed/~3/QpPiA1YSNlA/story01.htm Tyler Durden