Most forecasters are gloomy about global economic prospects.

According to Schroders, doyen of UK assets managers:

“We forecast a more stagflationary environment in 2019 with global growth set to slow and inflation to rise”.

The Davos World Economic Forum predicts a “sharp drop-off in world trade growth, which fell from over 5 per cent at the beginning of 2018 to nearly zero at the end”.

Forbes business magazine warns:

“The biggest problem for the global economy in 2019 will be massive business failures that could also lead to bank failures in emerging markets”.

Of course, the forecasters have been wrong before but it is clear that the main analysts of the global capitalist economy are pessimistic about current trends. They are right to be worried.

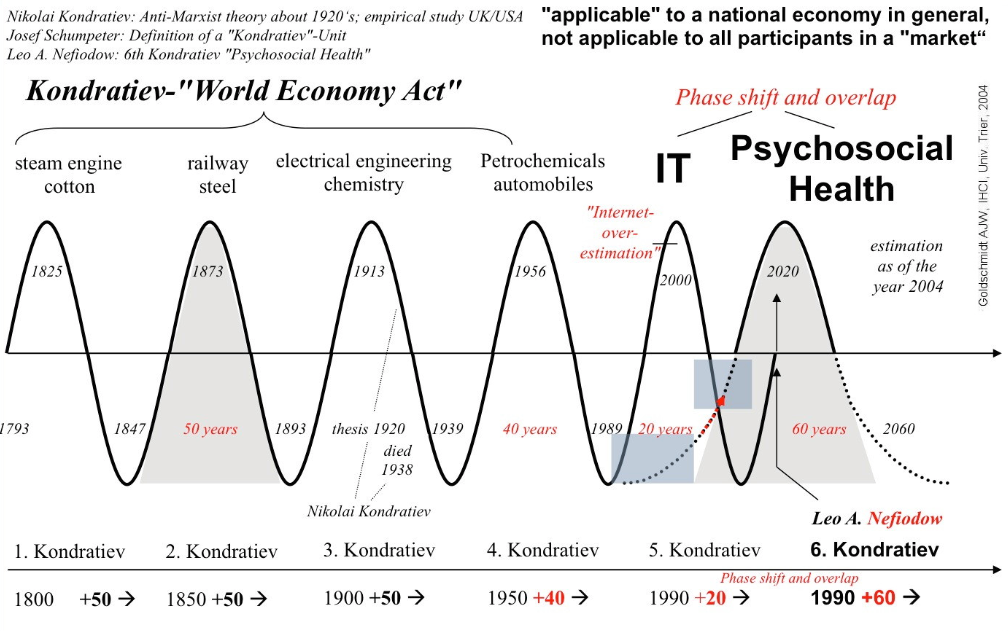

The international economy operates in pulses christened Kondratiev waves after Nicolai Kondratiev (1892-1938), the Russian economist and statistician who first identified them. These K-waves consist of an expansionary upswing lasting normally 15-20 years, followed by a downswing of similar length. We are now in such a downswing that could last till the 2030s.

What causes Kondratiev pulses?

There is a rich literature trying to identify the cause, in particular the work of the Belgian economist, the late, great Ernest Mandel. Crudely, it works like this. Social and economic conditions mature to spark a runaway investment boom in the latest cluster of new technologies. After a period, excess investment and increased competition lower rates of profitability, curbing the boom.

At the same time – because this is as much a sociological as an economic process – growth expands the global workforce, both in numbers and geographically. The new, militant workforce launches social struggles to capture some of the wealth created in the boom. This, in turn, adds to the squeeze on profits. The peak and early down wave are characterised by violent social conflicts, whose outcome determines the length of the contraction.

To date each K-wave has seen a crushing of social protest and a halt to wage growth, if not a fall in real incomes for the working class. Thus conditions accumulate for a fresh investment boom, as profitability recovers. The ultimate trigger for the new upcycle is investment in the next bunch of new technologies, which simultaneously provide monopoly profits and a new set of markets.

UPSWING OR DOWNSWING: WHERE ARE WE ON THE K-WAVE?

Where precisely are we in the Kondratiev cycle?

There is a dispute about this. Economists convinced by the Kondratiev theory largely agree there was a strong up-phase following the Second World War, lasting till the early 1970s. This was driven by the collapse in European wages imposed earlier by the Nazis and by the universal adoption of Fordist, mass production techniques. This expansion turned into a downswing in the 1970s and early 1980s, as profitability declined and the revived European economies (linked through the early Common Market) eroded American competitiveness.

The dispute concerns what happened next – the era of Reagan, Thatcher, neoliberalism and globalisation, running up to the present. In 1998, the American economic historian Robert Brenner published a hugely influential account of global capitalism which claimed to identify a super downswing running from circa 1970 to the turn of the millennium. Brenner rejected the notion global capitalism had (or was likely) to regain profitability, citing excess capacity rather than working class resistance as the primary driver. He pointed to the sudden stagnation in the Japanese economy, in the 1990s, as a precursor for the West’s future.

I have always believed that Brenner was not just wrong, but wildly wrong. The Reagan-Thatcher era created precisely the conditions for a new upswing, by smashing the trades unions and incorporating the former Soviet Union and Maoist China into an expanded capitalist market place, complete with hundreds of millions of new, cheap workers. The result was a boom based on investing in a cluster of new technologies: the silicon chip, the internet and mobile phone. On a political level, the social welfare gains of the working class won after WW2 were eroded, to reduce taxes and boost profits.

This upswing lasted till the Bank Crash of 2010. There were several significant features of the 1985-2010 up-wave. First, it was longer than the average, suggesting the current downturn could also be lengthy. Second, the neoliberal upswing involved a commercial and political victory for a rejuvenated US capitalism. Witness the current dominance of American high-tech. Europe, on the other hand, finds itself in decline, crushed between rival American and Chinese imperialisms. The crisis of the EU, Brexit included, results directly from this geopolitical shift.

The new downswing results from more than the 2008/9 financial crisis. There has been a wave of Chinese and Asian working-class resistance to exploitation, which has eroded profits. In the West, paradoxically, the historic defeat of the unions has flatlined wages. As a result, goods can be sold (and profits maintained) only by bolstering consumption through easy personal debt. That makes the Western capitalist model unsustainable and prone to endemic bank failure. The banks and their tame accounting firms are busy covering up this chronic instability via wholesale fraud. As a result, we are nowhere near the bottom of this K-wave.

What is the solution? I’ll discuss that next week.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2IgFNUk Tyler Durden