Shortly after we wrote about an online software engineering school that was allowing students to pay their tuition by forfeiting 17% of their income after they graduated, it’s becoming clearer that the model of selling an “equity stake in yourself” to fund tuition is making its way to the mainstream.

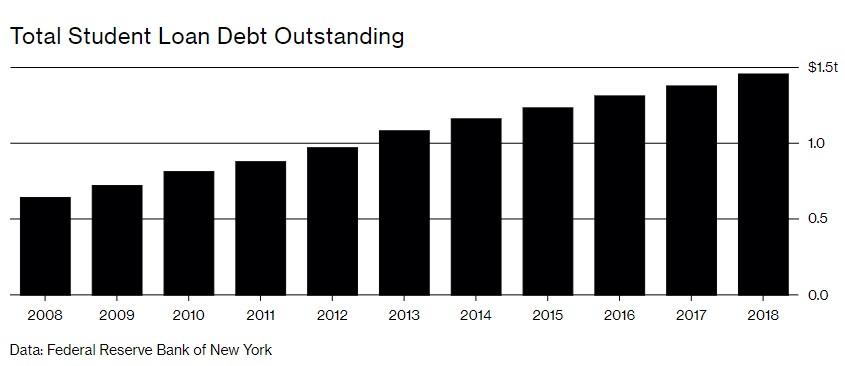

Equitizing students was the topic of an in-depth Bloomberg Businessweek look into the details of what Americans are doing to combat the $1.6 trillion in higher education debt that they owe. Specifically, the article followed the path of 23 year old Amy Wroblewski, who has been literally turning over a set percentage of her salary to investors – and will do so for the 8 1/2 years after graduating college.

Wroblewski makes about $50,000 a year as a higher education recruiter and surrenders about $279 a month to investors who helped pay for her tuition. If she winds up doing extremely well in her field, she may wind up paying twice as much. But if she loses her job, she won’t have to pay anything and investors will be stuck with the bill until she finds work. Wroblewski is part of a new program at Purdue University that sidesteps regular student loans in favor of allowing students to hand over future earnings through an “income sharing agreement”. The agreement turns students into equity investments, instead of debt notes.

And like any investment in equity, students require some amount of due diligence. Wroblewski’s history of always holding down two jobs and rising to vice president of Delta Sigma Pi, a business fraternity, attracted a company called Vemo Education, who made her the offer after vetting her as a “potential investment”.

Chuck Trafton, who runs hedge fund FlowPoint Capital Partners LP, which has invested in ISAs said: “I envision a whole new equity market for higher education in the next five years where today there’s only debt.”

The market for these types of agreements is now only in the tens of millions, a very small sliver of the $170 billion in outstanding asset backed securities from student loans. And only some some select schools are allowing outside investment firms to buy a stake in students. Others seek out individual donors, wealthy alumni or use money from their endowment. Purdue is the most high-profile school to implement such a program so far.

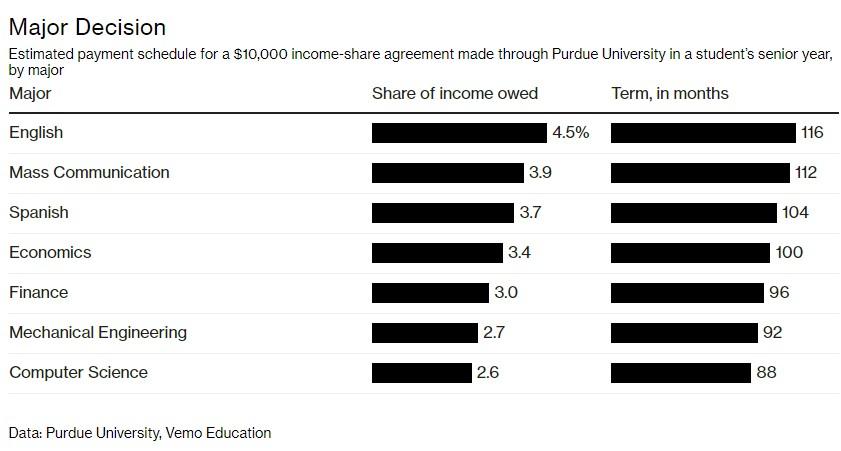

ISA investors ask for a smaller “piece of the pie” from students with more lucrative majors. For example, at Purdue, English majors pay 4.52% of their future income over 10 years, whereas chemical engineers paid 2.57% in a little over seven years.

The program is set up to be competitive with student loans:

Consider a junior economics major who needs $10,000. Through a private loan, she’d likely pay $146 a month, or $17,576 over the course of 10 years. Through an ISA, a student with a starting salary of $47,000, Purdue’s estimate for its 2020 economics graduates, would pay $15,673, assuming 3.8 percent annual salary increases. That would be a good deal. But, if she found a $60,000-a-year job, she’d have to fork over $20,010.

But financial firms and for-profit colleges are, naturally, still trying to turn a buck. These ISAs may have a luster to them now, because they are a new instrument, but students still wind up paying back more than they borrow.

Julie Margetta Morgan, a fellow who studies higher education at the Roosevelt Institute said: “There’s a level of enthusiasm that’s overstated. It’s pretty darn near impossible to say whether an ISA is better or worse for an individual.”

The last time something like ISAs were tried, at Yale in the 1970s, it wound up in many students defaulting, leaving borrowers waiting for longer than they had anticipated to get paid. The goal then was to pool all borrowers and have them pay the school a percentage of their income for 35 years. Yale ultimately wound up bailing out the borrowers (preparing them for their futures on Wall Street) and winding down the program in 2001. And the terms of some of these plans weren’t capped in any way. One graduate, Juan Leon, borrowed $1500 through the program and wound up paying back $8000.

“We didn’t read the fine print. It was quite, quite onerous,” Leon said.

Under these new plans, like Purdue’s, students have more protection. Purdue caps total payments at 2.5 times what a student borrows, so that the most successful students don’t feel like they’re being gouged. Students making less than $20,000 a year aren’t charged at all, as long as they are working full-time or in the process of seeking work. These payments are instead deferred.

So far, Purdue has arranged about 700 of these contracts worth about $9.5 million and they have closed $17 million in investments from two funds. David Cooper, the chief investment officer for Purdue, hoped to develop the program and pitch it to investors after overseeing Indiana‘s retirement system.

“We feel like we’ve got the pricing for the students at a pretty good spot. At the same time, it’s a reasonable return for the investors,” he said.

Charlotte Hebert graduated from Purdue in 2017 and doesn’t share Cooper’s enthusiasm about the $27,000 she took to pay for her schooling costs. She’s going to be required to shell out 10% of her income for the term of her deal, which is about 2.5% more than what an engineer would pay. She makes about $38,000 a year as a writer and pays investors $312 a month.

“I don’t think it’s the perfect solution. I am of the opinion that in a society where most of its workers need a college education, nobody should be paying this much to be what is considered a functional member of society,” she concluded.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2G9FZ53 Tyler Durden