Late last Friday, we reported that several hours after the market close, China’s financial regulator and central bank made a shocking announcement: for the first time in nearly 30 year, China would take control of a bank, in this case the troubled inner Mongolia-based Baoshang Bank, due to the serious credit risks it poses.

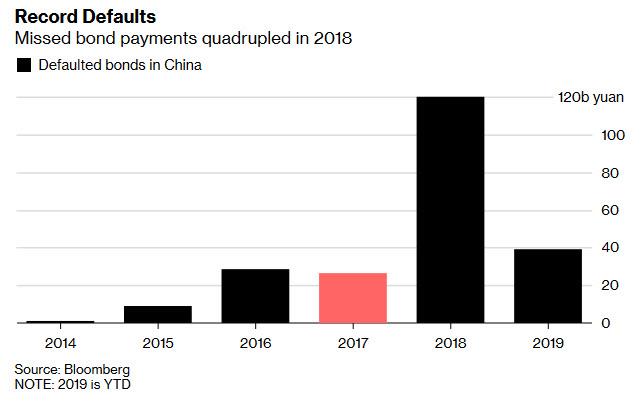

The news which highlights the potential for increased stress at regional lenders that piled into off-book financing in recent years, was strategically timed to hit ahead of the weekend, and with the market closed, it avoided an immediate panic selling waterfall. However, the fact that in China banks are now fair game for failure, and will soon join the record surge in Chinese corporate defaults…

… slammed the country’s financial sector on Monday, sending funding costs sharply higher and underscoring the potential for increased stress at regional lenders that piled into off-book financing in recent years.

Unfortunately for Beijing, Bloomberg writes overnight that despite the strategically timed news, it wasn’t enough to prevent turmoil from sweep across the nation’s bond market, where funding costs for lenders surged and yields on government debt jumped. The seven-day repurchase rate jumped 30 basis points to 2.85%, the highest in a month, as of late Monday in Shanghai, while the yield on 10Y sovereign bonds climbed 5 bps to 3.35%.

“Baoshang’s case is a big wake-up call,” said Becky Liu, head of China macro strategy at Standard Chartered. “Participants in the interbank market, who didn’t differentiate credit when lending to banks on the belief that they will never go bankrupt, have now become more cautious. That has helped drive up funding costs and thus sovereign yields.”

Meanwhile, citing traders, Bloomberg also noted that the market is getting increasingly concerned that smaller banks may sell or refrain from buying government bonds because of difficulty getting funding, pressuring sovereign debt further, Liu said.

While a full-blown bank run has yet to emerge, Baoshang Bank’s negotiable certificates of deposits and other bonds were suspended from trading Monday morning. Analysts said the takeover will hurt market sentiment on debt and shares of smaller banks and their issuance of NCDs could be harder from now on. The outstanding bonds of other city and rural commercial banks in similar situations could be sold off, China Merchants Bank said in a note.

For those who missed our prior post on the bank collapse, here is some context:

Founded in 1998, Baoshang has more than 8,000 staff and reported total assets of 576 billion yuan ($83 billion) at the end of September 2017 — a fraction of CCB’s 23 trillion yuan last year. The smaller bank’s so-called investment receivables, which analysts have said are often loans disguised as investments, stood at 153 billion yuan, accounting for more than a quarter of total assets.

Yet despite promises of recovery, with the Mongolian bank now insolvent, China’s Caixin reported that interbank creditors with deposits above 50m yuan may get back 70% of principal payment and corporate creditors may get no less than 80% at early stage. More concerning is that depositors will also be burned: while small, individual savings at the bank will be guaranteed by the government, corporate deposits and interbank liabilities above 50 million yuan will be negotiated, the regulators said on Sunday.

Finally, the cost on China’s one-year interest-rate swaps, a measure of traders’ expectations for liquidity conditions, surged 7 basis points to 2.82%. That’s largest increase in a month.

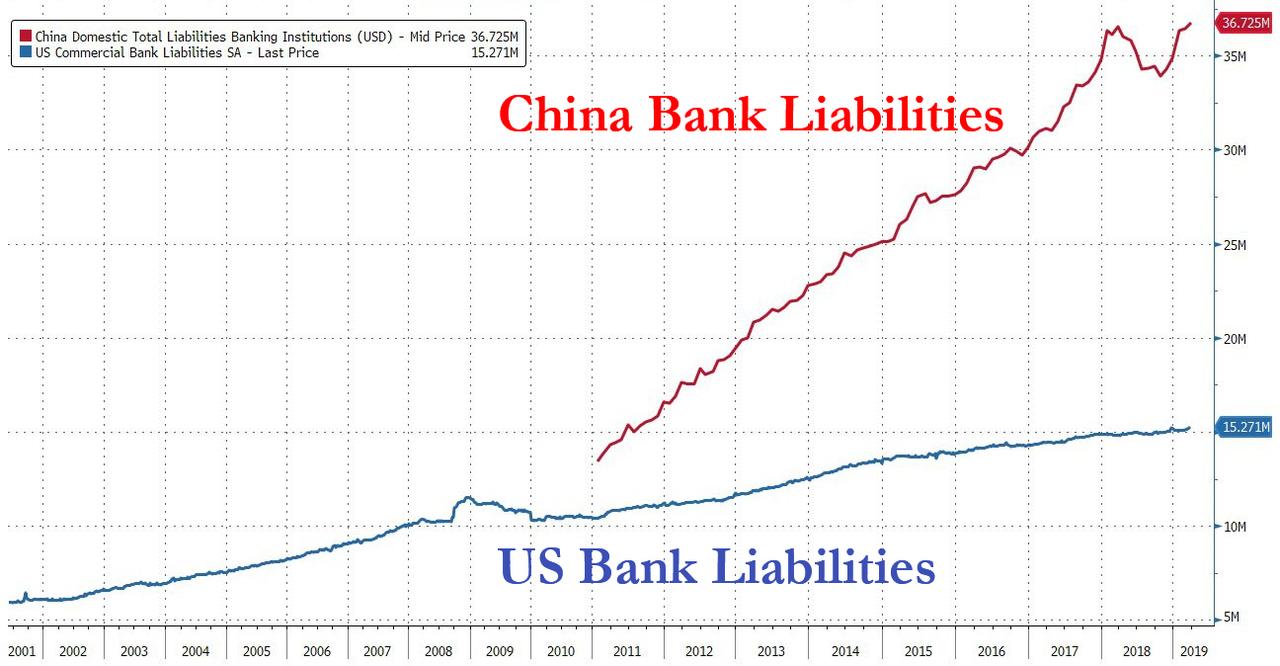

In short, what has just transpired is a bail-out with Chinese bail-in characteristics, and in other words, this may well have been the first domino to fall in China’s banking sector which earlier today reported a record 268.5 trillion yuan ($38.9 trillion) in liabilities and 246.2 trillion yuan ($35.6 trillion) in assets, both up roughly 8% Y/Y, and well over double the size of the American banking sector.

Perhaps the market is waking up that once the dominoes start falling, It will be next to impossible for Beijing to prevent a crash in the world’s largest banking system. It’s also why the debt sold offshore by Chinese small banks to help meet capital requirements also fell, with Bank of Chongqing’s $750 million Additional Tier 1 note was down 0.8 cents on the dollar, the biggest fall since March 20, to 94 cents. Securities from Bank of Zhengzhou and Huishang Bank also dropped.

If or rather when more banks suffer Baoshang’s fate, the drops will be far greater.

Ironically, Baoshang which was once seen “as a model for funding China’s regional economies” according to Bloomberg, is one of many smaller Chinese lenders that obscured its exposure to risky borrowers by tapping into the country’s shadow-financing system. And while China has been cracking down on such behavior, but UBS Group AG analyst Jason Bedford said the country is rife with regional banks that used special-purpose vehicles to circumvent lending restrictions and hide the true state of their bad loans.

What is even bizarre, is that as we noted last week, the bank’s “official” non-performing loan ratio then was only 1.68% as of December 2016. That, in itself, would never have been sufficient to force a takeover, and suggests that not only was the bank’s real bad debt ratio much higher, but that China continues to chronically under-represent the true state of its NPLs to avoid bank runs.

Whatever the underlying ugly truth may be, it’s not as if investors and depositors weren’t warned.

As discussed here extensively in 2016 and 2017 (see “Some Chinese Banks Suspend “Interbank Business” As Regulator Demands That Collateral “Actually Exists“), regional banks in China’s rust belt drove the rapid expansion of non-traditional lending that peaked in early 2018. As a result, smaller firms, who used shadow-loan instruments to diversify from their struggling home provinces, exposed themselves to a much wider spectrum of Chinese corporate risk.

Now that the “shadow bubble” has popped, banks are now getting squeezed as Chinese companies default at a record pace and financing costs for shadow-lending activities increase. As part of the government clampdown, banks have been forced to reclassify loans overdue for more than 90 days as non-performing, a move that led to a record surge in soured debt and wiped out capital at some small lenders, Bloomberg reports.

And now that Baoshang is insolvent, and the de facto canary in Chinese bank failure coalmine (there will be many more) the question is how to restructure its insolveny balance sheet: the bank has more than 60 billion yuan of negotiable certificates of deposit and 6.5 billion yuan of subordinated bonds outstanding, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Trading in the the company’s NCDs and other bonds was suspended on Monday, people familiar with the matter said.

Why do NCD’s matter? Because as we explained as far back as two years ago, in the most recent troubling trend involving Chinese banks, numerous smaller banks had become acutely reliant on such shadow banking funding mechanism as Certificates of Deposit, which had become the primary source of short-term funding for many of China’s banks mid-size and smaller banks.

As Deutsche Bank further explained, the banks most exposed to a shut down in this “shadow funding” pathway are medium-sized and small banks, for whom as of 1H16, wholesale funding made up 31% and 23%, a number that has risen substantially in the interim period.

And with the Baoshang domino now down, and the interbanking funding market suddenly freezing, Friday’s announcement will put shares of other Chinese banks under pressure, according to Sanford C. Bernstein. A Bloomberg Intelligence index of Chinese lenders dropped 0.9% on Monday to a four-month low. Predictably, ICBC, the nation’s largest lender, slipped 0.5% in Hong Kong.

Some tried to put a positive spin on the shocking failure: “Low quality, small regional banks are unlikely to pose systematic risks to the financial system or the operations of the big SOE and joint stock banks,” said analysts Linda Sun-Mattison and Jason Li in a note on Monday. “However, the bail out of Baoshang Bank, a rare move by the government, and the involvement of CCB will no doubt heighten investor concerns over SOE banks’ risk exposure to national service.”

Translation: nobody knows yet if this bank failure will result in a bank run, even as the market is clearly recoiling from the bail out. If a bank run does indeed materialize, and some of those $35 trillion in Chinese bank liabilities (i.e. deposits) flee… well, not only are all bets off, but Trump can celebrate an early victory in the US-China trade war.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2WmNSOX Tyler Durden