One of the most difficult things for a bank to admit is that its forecasts about the markets and economy have been wrong.

In recent weeks we have observed just this phenomenon, as one bank after another admitted their rates forecasts for 2019 were dead wrong (thanks to the resurgence of growth-sapping trade war), and the result has been a dramatic cutting in 10Y yield forecasts for the end of the year, which started with Bank of America two weeks ago when the bank admitted it was “unrealistically optimistic” ahead of coming “rate misery” when it cut its year-end 10Y yield forecast from 3.00% to 2.60%. Incidentally, today Bank of America was also one of the first to cut its year end S&P forecasts, stating that “we cut our 2019E EPS by 1.2% to $166 from $168 and 2020E EPS by 2.2% to $176 from $180, on renewed trade tensions between the US and China, plus new tariffs on Mexico. Increased China tariffs would lower the S&P’s EPS by an additional ~1% and tariffs on Mexico could represent a 0.6% drag in 2019, then -1.5% in 2020.”

In any case, at the time BofA cuts it rates forecast, we said that “now that BofA has thrown in the towel, expect the rest of Wall Street to do the same, admitting they too got absolutely everything wrong on the bond side.” Sure enough, today JPMorgan did just that when it said that it now sees 10-year Treasury yields at 1.75% at year-end, compared with 2.45% previously. The forecast for March is 1.65%. The bank also sees two-year yields at 1.40% in December and 1.30% in March, after the bank last week announced it now expects two rate cuts by the Fed before year end: one quarter point cut in September and December. Other banks have also piled on and Barclays notably now expecting no less than three rate cuts in the second half of the year.

Yet even as one after another Wall Street bank takes the machete to its forecasts, one bank has remained resolute in its projections, and despite the ongoing projection carnage, has refused to cut either its Fed rate forecast or its 10Y interest rate forecast.

That bank is Goldman Sachs, the same Goldman which we referenced last Friday when we said that “a financial cage match is forming between Goldman and JPMorgan”:

In the hawkish corner we have Goldman’s chief economist, Jan Hatzius who until very recently was expecting no rate cuts in the coming year, and in fact is anticipating the Fed will hike toward the end of 2020, arguably as a result of the upcoming inflationary spike as a result of trade war. In the dovish corner, we have JP Morgan which as of this morning has turned so bearish that the latest report from the bank’s chief economist, Michael Feroli, says that “Making Abysmal Growth Attainable” again would require not one but two rate cuts before the end of 2020!

But while Goldman stubbornly refuses to trim either its rate, market and GDP forecasts, today it made a small but notable adjustment to one of its core views: the bank’s heretofore optimistic take on how the trade war plays out.

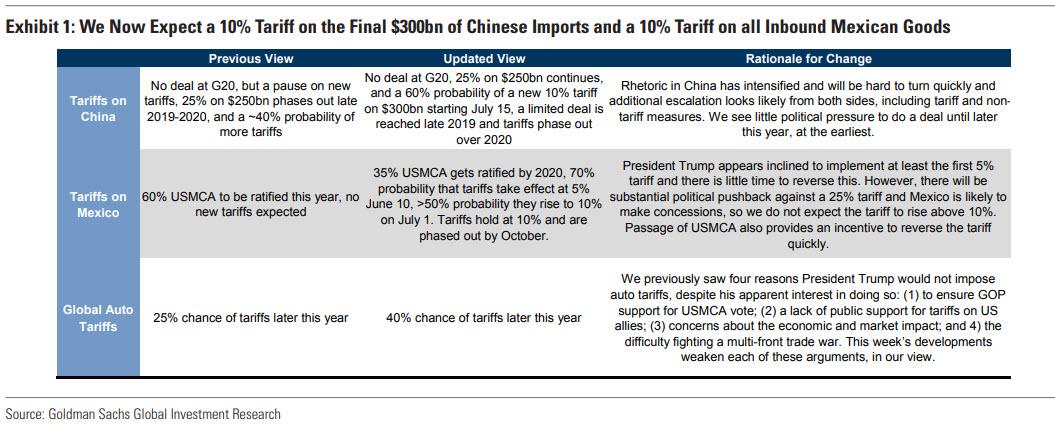

Long story short, Goldman is no longer optimistic, and as Jan Hatzius writes, “we have revised our trade war assumptions and now expect a 10% tariff rate by July on both the final $300bn of Chinese imports (60% subjective odds) and on all Mexican products (70% odds for the first 5%, and just over 50% odds for the step-up to 10%). For China, this represents a middle ground between our previous assumption of a delay following the G20 summit in late June and the full 25% across-the-board tariff proposed by the US Trade Representative.”

First some more details on China:

New tariffs on all imports from China, some additional non-tariff restrictions, and no deal until late 2019…. While there is still a clear possibility that a meeting between Presidents Trump and Xi at the G20 summit on June 28-29 could avert further escalation, we believe the probability has risen that the next round of tariffs will take effect and we now view this as the base case (60% probability).

The probability of this next round has risen, in our view, because both sides continue to escalate the dispute with increasingly confrontational rhetoric and new forms of non-tariff retaliation. Moreover, while we believe that both sides would ultimately like to reach an agreement, neither side appears to be under much political pressure to do so at the moment. That said, we continue to expect that President Trump will want to announce some type of agreement with China to lower those tariffs by late 2019 or early 2020. This would allow consumers—and likely equity markets—to benefit prior to the 2020 presidential election.

How does trade war with China end?

It seems likely that by later this year both sides will become more interested in reaching an agreement as the economic and political costs of tariffs and other trade restrictions mount. We assume that the US and China will reach an agreement late in 2019 that reduces—but probably does not eliminate—US tariffs in return for policy concessions from China. However, we do not expect that the US and China will conclude a far-reaching agreement, as had seemed likely only a few weeks ago. Indeed, even a deal later this year should not be expected to resolve all the differences between the two countries (and residual uncertainty is likely to remain about whether tariffs could be re-introduced at a later date).

Next, Goldman’s view on Mexican tariffs:

New tariffs on Mexico take effect temporarily but stop short of 25%. President Trump has proposed a 5% tariff on all goods entering the US from Mexico effective June 10. The tariff would increase by 5pp on July 1 and every month thereafter until it reaches 25%, where it would remain until the President determines that Mexico “substantially stops the illegal inflow of aliens coming through its territory.” According to the White House, avoiding the tariffs would require Mexico to secure the Mexico-Guatemala border, crack down on criminal organizations, and establish a “safe third country agreement” to prevent asylum seekers entering Mexico from claiming asylum in the US.

In light of the fact that these tariffs would take effect in less than 10 days and include a number of specific conditions, we believe it is fairly likely (70% probability) that at least the 5% tariff takes effect. That said, the President threatened another high-profile immigration-related action—closing the US-Mexico border—but never implemented it, raising the possibility that this might also be a false alarm. While this is clearly possible, we believe the proposed tariff is more likely to take effect since a 5% tariff would be less disruptive than a full border closing.

We believe it is a closer call as to whether the rate steps up to 10% on July 1, but see this as slightly more likely than not given the short time that Mexico would have to make reforms and the possibility that US-Mexico relations deteriorate once the first round of tariffs has taken effect, as occurred with US-China relations. However, we expect that tariff escalation would stop at 10% and that a resolution is likely to be reached in the next few months that would eliminate the tariff. We do not expect the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) to be ratified as long as this tariff is in effect .

At this stage, we believe the Mexican authorities want to engage and may not immediately retaliate. On the three main White House demands (secure the Mexico-Guatemala border, crack down on criminal organizations, and establish a “safe third country agreement”), we see scope for compromise as all three are issues that interest and benefit Mexican authorities as well (though progress on the third could be constrained by domestic politics and sensibilities).

But wait, there’s more: as Hatzius admits, “additional tariff rate increases or an across-the-board auto tariff are also possible but not our base case. We still expect deals with China and Mexico to lead to a removal of the tariffs, but not until late 2019/2020.”

Goldman’s various scenarios sumamarized visually:

In other words, expect a long and painful trade war which will conclude in early 2020 at the earliest.

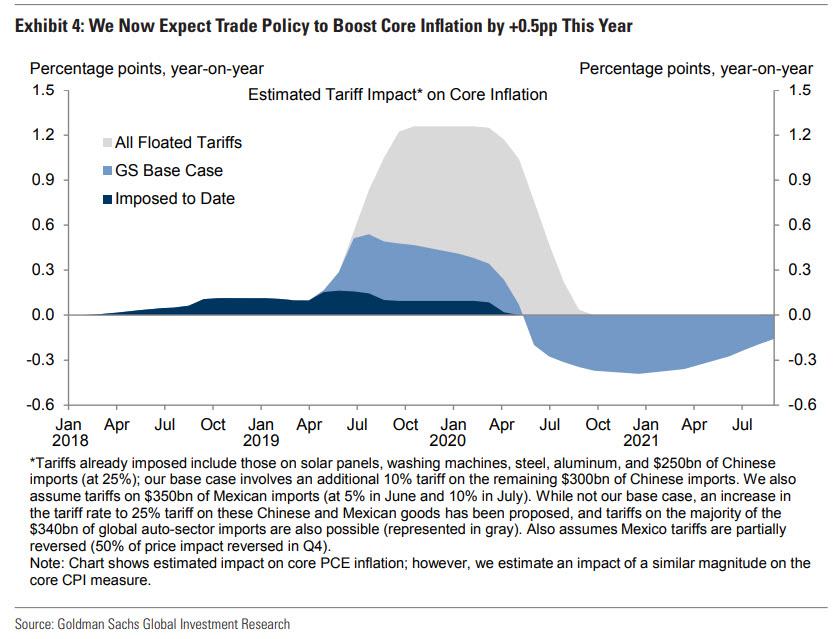

What happens next? Here, as we observed most recently this morning, Goldman is confident that accelerating trade wars will impact prices, pushing them sharply higher, and in effect resulting in a stagflationary outcome, to wit:

The trade war is likely to become increasingly visible in the inflation numbers. Our new core PCE forecast incorporates a ½pp tariff boost and sees inflation climbing from 1.57% in April to 2% in August and to 2.3%-2.4% in early 2020, before diminishing under our assumption of tariff removal. If all proposed tariffs are implemented, we estimate a peak core inflation boost of +1¼pp.

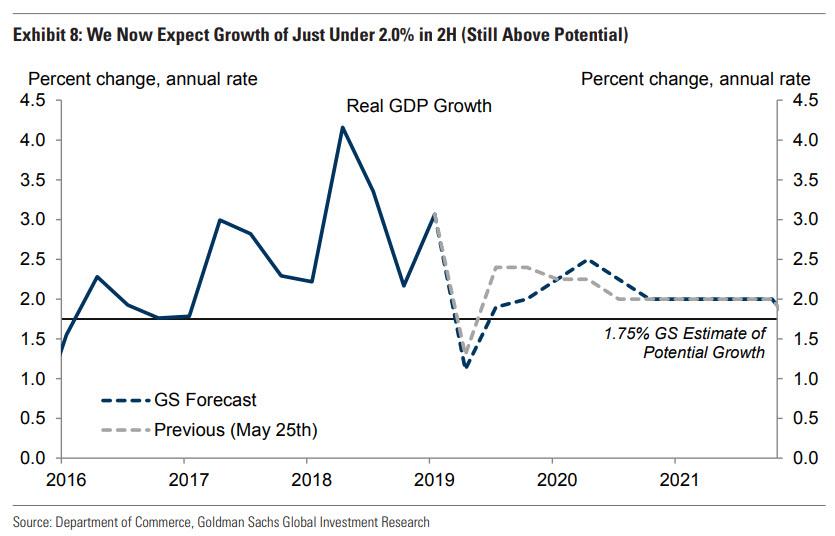

So while Goldman expects cost-push (certainly not demand-pull) inflation to hit over the next 12 months, the bank notes that while growth effects are much less predictable, it still just took off a 0.5% from its previous 2.5% H2 GDP forecast, to wit:

“financial conditions have already tightened by about 50bp, and we attribute some of the weakness in the survey data in late May to the impact of the escalating trade war. On the back of these developments, we are lowering our H2 GDP forecast by about ½pp to 2%. We expect growth to rebound moderately in 2020 as tariffs come off and financial conditions stabilize.“

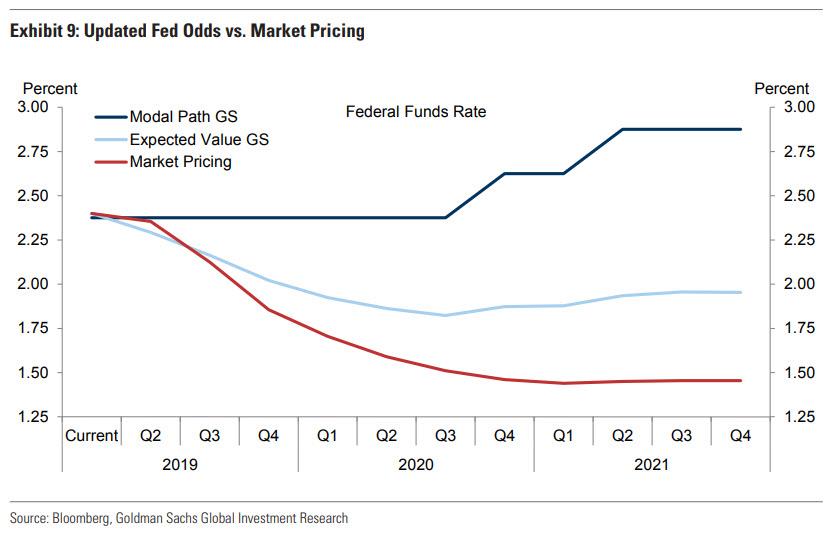

Yet while Goldman was willing to admit it was wrong in its complacent outlook on trade war, it still remains stubborn in refusing to cut its Fed Funds rate forecast, even as all its peers are doing just that. Well, it may no tbe cutting it explicitly, but it sure is doing so as implicitly as it can, in a kinda, sorta way:

Because of the downside risks to growth, we have sharply raised our subjective probabilities for Fed rate cuts. But while it is a close call, the outlook has not yet changed enough for cuts to become our baseline forecast. So far, the FCI move has been far smaller than those of 2015-2016 and 2018, and while some further tightening is likely, we still don’t expect output and employment growth to fall below trend. With only a moderate tightening in financial conditions, still-decent growth, and inflation headed above 2%, cutting rates could look overly political in light of President Trump’s vocal demands for easier policy.

To be sure, what the Fed does next is without doubt the most important question: will Powell cut as a result of deflation, or will the rising price component of the upcoming stagflation be enough to pressure to Fed from cutting rates and in fact will the FOMC hike rates? Here is Goldman’s discussion on the topic:

There is no question that the probability of cuts in the remainder of 2019 has risen, owing to a combination of the tightening in financial conditions and the associated deterioration in the near-term growth outlook, continued below- target inflation, and increased acknowledgment on the Fed’s part—e.g. in Vice Chair Clarida’s speech last Thursday—that the risks are tilted toward cuts. We have therefore sharply lifted our subjective probabilities of cuts, for example raising our odds for Q3 and Q4 by 19pp each (to 28% and 31%). Our updated modal and expected funds rate paths are shown in Exhibit 9.

But while it is a close call, we have not yet seen enough of a change in the outlook to adopt a baseline expectation of rate cuts.

On the growth and employment side, even our revised forecast looks for growth slightly above trend and a mild downward trend in the unemployment rate as the drag from financial conditions gradually diminishes and the strength of household demand offsets the weakness in business investment. The main reason for these relatively limited changes is that financial conditions have only tightened moderately so far. Admittedly, part of this relative reflects the 50bp rally in the bond market over the past three months, which in turn is partly predicated on the expectation of Fed easing. So a decision by the FOMC not to deliver on this expectation could result in further FCI tightening.

Meanwhile, on the inflation side, we share Chair Powell’s view expressed at the May 1 FOMC press conference that the current weakness in the PCE ex food and energy is largely temporary. In fact, the most recent data have reinforced this view. The PCE ex food and energy rose a firm 0.247% in April and the Dallas Fed’s trimmed-mean PCE index showed its largest month-to-month increase of the entire expansion and now stands at a year-on-year rate of just over 2.0%, as illustrated in Exhibit 10. The news on household inflation expectations has also been fairly solid, with a rise in the University of Michigan’s 5-10 year consumer measure in May to 2.6%, the top end of the range seen in the past three years. Combined with the prospective tariff impact, these signals increase our confidence that the PCE ex food and energy measure will indeed rise above 2% by early 2020.

So our baseline is still one in which unemployment moves sideways or lower from levels that are already below the FOMC’s estimate of the sustainable rate, while inflation is above the 2% target. If this forecast is correct, a decision to cut on the basis of a relatively limited tightening in financial conditions might well look overly political in light of President Trump’s vocal demands for easier policy. Since Fed officials must think not just about near-term risk management but also about the longer-term credibility and political independence of the institution, this might be another reason to resist cuts, barring a bigger shift in the outlook for employment and inflation.

So after that lengthy apology that it had been largely wrong about much if not all, and cognizant that it will likely continue to be wrong in a world in which the market and economy flip by 180 degrees depending on what Trump may tweet at any given moment, Goldman warns that it will probably be wrong yet again:

There are several ways in which our decision to buck the trend toward forecasting rate cuts could prove ill-advised. Perhaps the slowdown in some of the May business surveys sets the stage for a sharp deterioration in the first-tier ISM and employment releases in the coming week. Perhaps the weakness in the PCE ex food and energy will persist for one reason or another. And most importantly, perhaps the US-China escalation will continue until the impact on business confidence and financial conditions is sufficiently severe to force a change, including in the FOMC’s policy.

The bank’s conclusion: “we will continue to evaluate our view in light of changes in the economic data, the policy environment, and financial conditions, and make changes as appropriate.” And since these days Goldman is best known for abusing its clients’ balance sheet as it unloads existing positions before taking the other side of whatever trade it is recommending via its public-facing research, once Goldman does reverse and predicts rate cuts, that will be the sign that the bottom is once again in.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2Mrqbkw Tyler Durden