Authored by Johanna Ross via ConsortiumNews.com,

The EU elections raise questions about the territorial integrity of the UK…

They were the elections that weren’t supposed to take place, but wound up proving highly significant for British politics. By now the U.K. should have divorced itself from the EU under Prime Minister Theresa May’s promise of “Brexit means Brexit.” But with her leadership turning out to be not so “strong and stable,” Britain finds itself still part of Europe. As a result, on May 23, voters in the European Parliament election seized the chance to send a resounding message to traditional centrist parties that the duopoly that has dominated U.K. politics since World War II — Conservative and Labour — is no more. Change is afoot.

Despite two years of disastrous Brexit negotiations with deal after deal blocked by Westminster politicians and considerable attempts by Remain (in EU) supporters, including former Prime Minister Tony Blair, to lobby for a second referendum on Brexit, the indefatigable Nigel Farage led his Brexit Party to decisive victory, claiming 32 percent of the vote.

Nigel Farage: Led Brexit Party to decisive victory. (Gage Skidmore, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Taken at face value this result has reinforced the 2016 EU referendum result with a clear message: the U.K. wants out of Europe.

Scotland Always More Pro-Europe

But a map of the voting ratio tells a different story in Scotland. As predicted, it was a historic result for the governing Scottish National Party, which stood on a Remain platform, advocating a second referendum. Their 38 percent vote rose from 29 percent in the last EU election five years ago. The Brexit Party by contrast secured just under 15 percent. As Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon concluded, Scotland has reinforced its pro-EU stance.

From the days of the Auld Alliance with France, long before the 1707 unification with England, Scotland has had its own relationship with the Continent. Links with universities such as Leiden in the Netherlands and trade links with Bruges, Belgium, and Gdansk, Poland, were in place long before similar connections were made with England.

Scotland has always been more pro-Europe and this election result emphasized that. It’s already being hailed as the necessary catalyst for a second referendum on Scottish independence or “IndyRef2” as it’s known closer to home. Nationalists have been calling for this since they were defeated 45 percent to 55 percent in the 2014 vote. But Sturgeon stuck to her guns, saying that the time was not right; as polls confirmed. However, less than a week after the EU election, the SNP has already published a new independence bill, declaring the EU election result a “fresh start” for Indyref2. A deadline has been set for May 2021.

Sturgeon: Scotland’s pro-EU stance reinforced. (Wikimedia Commons)

Westminster can of course try to block any second referendum. At least three of the candidates to replace May have said they would. But that could court a serious backlash. More and more Scots believe that London is no longer interested in their views on anything, with the Brexit negotiations amply demonstrating this. As Scottish historian Tom Devine has commented, the Brexit talks demonstrated that any idea of a union based on “partnership and mutual respect” is “fraud and myth.” Under the circumstances, it is not far-fetched to envisage a Catalonia-style situation in which Scotland forges ahead with a second referendum in spite of Westminster.

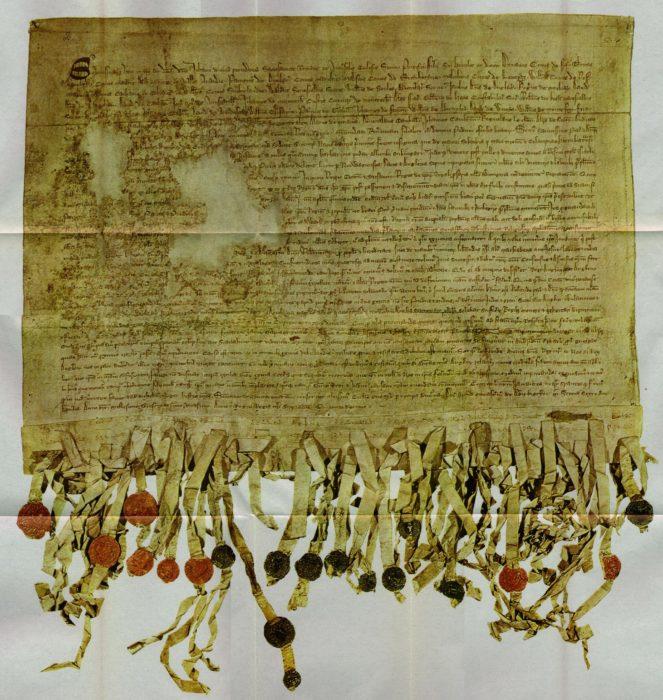

In such an instance Scotland may get more support from EU allies than Catalonia did. Britain’s reputation in Europe, after all, has been severely damaged over Brexit, and the EU is, arguably, more likely to back a country interested in joining Europe, than one that has rejected it. In any case, it wouldn’t be the first time Scotland made such a move. In 1320 the Declaration of Arbroath was sent to the Pope, signed by 50 Scottish nobles and proclaimed Scotland’s independence.

The “Tyninghame” copy of Arbroath Declaration from 1320. (Scotland barons via Wikimedia Commons)

Then there is the question of leadership. Sturgeon, in contrast to her Westminster counterpart, is widely trusted and respected in Scotland. Unlike May, she has provided the one thing that citizens value in a leader: consistency. Despite criticism for not calling another referendum to date, she stuck to her strategy – and it has paid off. The next campaign for independence is sure to be more effective this time around. It was widely agreed that the economic arguments for independence were the weakest link in the Yes campaign back in 2014. Aware of this, the Nationalists are publishing a guide on the subject, to be delivered to 2.4 million Scottish households this summer.

All indicators now are pointing to a no-deal Brexit, which will only boost the nationalists’ case. It could also potentially create chaos in another part of the United Kingdom—the island of Ireland.

Ireland’s Borders

Leaving without a deal would be the worst-case scenario for anyone who has any memory of the Northern Ireland Troubles. It’s feared that a hard border between north and south — which would occur if Northern Ireland, as part of the U.K., left the EU — with all the strict control and customs checks that the EU requires on its borders — could trigger a return to the days of bombings and shootings and jeopardise everything achieved under the Good Friday Agreement. It would be the ultimate provocation to Irish nationalist paramilitary groups who believe in a United Ireland.

A hard border, therefore, would be deemed a step back into the dark days of conflict, which no-one wants given all the lives that were lost to it throughout the 20th century. Indeed, times have changed and so has the political landscape on the Emerald Isle. The Irish Republic has benefited from EU and Eurozone membership and for many in the north has seemed like a beacon of economic prosperity. By contrast, Northern Ireland doesn’t even have a government — as the power-sharing agreement between the nationalists and unionists broke down two years ago — and the economic outlook is clouded by Brexit.

U.K.–Republic of Ireland border crosses this road at Killeen, marked only by a speed limit in km/h. Northern Ireland uses mph. (Oliver Dixon, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

These factors — together with a majority of Northern Irish voting to remain in the EU in the 2016 referendum — have therefore raised an idea that would have seemed unthinkable just a few years ago: that of Irish reunification. Earlier this year several U.K. cabinet ministers cited a “very real” prospect that a no-deal Brexit would lead to a vote on Irish reunification. Polls both north and south of the border have indicated increasing desire on both sides for this to happen. Granted, a united Ireland naturally brings its own set of obstacles and it’s not something to count on happening tomorrow. It is remarkable, nonetheless, that it is even being discussed.

All this raises the real possibility of the dissolution of the United Kingdom. Poor, inconsistent leadership from May, and a Westminster parliament that has put party politics and self-interest before the delivery of Brexit, has created the current crisis, which in turn has been a gift to Scottish and Irish nationalists.

What previously may have been considered a risky, unstable option for some voters — independence — no doubt now looks like a safer bet given the quagmire of Brexit. Voters now have to weigh up if it is in their interest to remain inside a union that no longer serves the Scottish people (some would argue never did).

As Robert Burns, Scotland’s 18thcentury bard, put it: “I have long said to myself, what are the advantages Scotland reaps from this so called Union, that can counterbalance the annihilation of her independence and her very name?” More than 200 years later, Scots are still pondering the same question.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2wGEOFV Tyler Durden