Authored by Thomas Kirchner and Paul Hoffmeister via CamelotPortfolios.com,

With protests by yellow vests in France approaching their six month anniversary and the European economy showing signs of not a temporary dip, but prolonged weakening, it is a good moment to take a step back and analyze the current situation as well as its implications for the medium to long-term outlook for Europe.

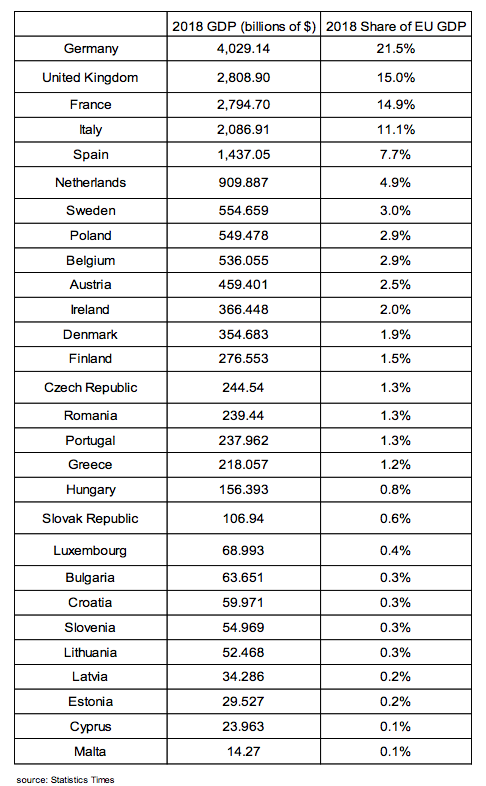

As we see it, European economies have been weakening significantly, and even worse, Germany, the European Union’s largest economy comprising almost 21% of the area’s GDP in 2018, is on the verge of recession. With Germany the economic locomotive of the euro area, there may not be much reason to be optimistic. The country’s economic problems appear to be structural, due to high taxes, excessive government spending, failed energy policies and other regulatory constraints. Thinking about the years ahead, we aren’t optimistic that the policy response from the German government — as well as other European governments such as in France, Italy and Greece — will be strong enough to avoid a prolonged economic malaise for the continent. As a result, we believe that the global economy will suffer from Eurosclerosis in the coming years.

Figure 1: GDP of EU Member States and Share of Total. Source: Statistics Times.

Struggling European Economies

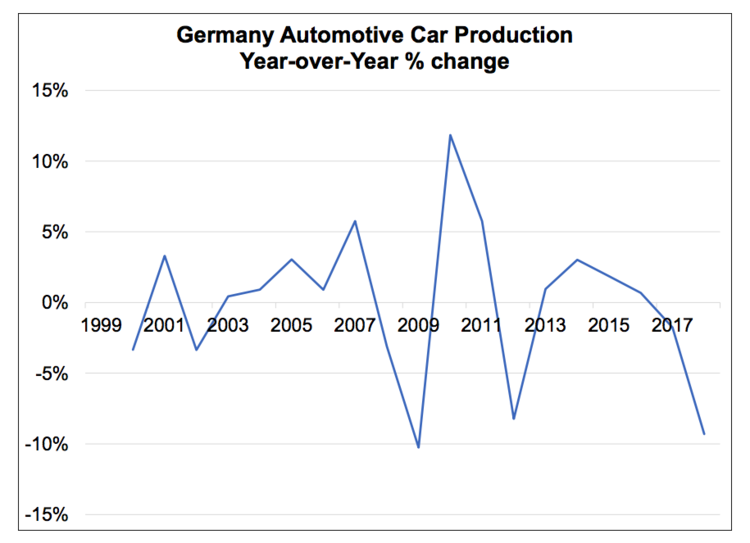

According to the OICA, automobile production in Germany fell 9.3% in 2018, year-over-year. In our view, the prospects for Europe’s leading economy are ominous given that the auto industry is linked to almost 8%% of German GDP. Business sentiment in Germany appears to have recently turned from euphoria to gloom: as of April 2019, IFO business sentiment has declined 2.8% while the Markit/BME purchasing managers index has crashed from 58.1 to 44.5 year-over-year.

Figure 2: German Automotive Car Production. Source: International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers

Optimists could point to low unemployment in Germany, which hovers near 5%, according to the OECD. But low unemployment data could be misleading because German companies can be reluctant to lay off workers, not only because restrictive labor laws make layoffs difficult and expensive, but also because hiring talent can be a lengthy drawn-out process should the economy recover quickly. Many firms experienced that problem during the last decade of relative economic strength when qualified labor was hard to come by and growth for some firms remained below potential due to labor shortages. While this helps to sustain economic statistics, it can destroy corporate profitability and eventually end up costing investors.

According to Eurostat, real GDP growth in Germany is waning, growing only 0.6% in Q4 2018, from 2.8% in Q4 2017. We are worried about the specter that when Europe’s economic locomotive sneezes, the rest of the continent catches a cold.

Unfortunately, the situation in most of Europe is just as gloomy. According to Eurostat, Italy experienced 0% growth in real GDP year-over-year in Q4 2018 (compared to 1.7% in Q4 2017), while France’s real GDP grew 1.0% in Q 2018 (compared to 2.8% in Q4 2017). While Italy seems hard pressed to enact aggressive pro-growth stimulus due to European Union budgetary rules, there doesn’t seem to be much appetite by President Macron to catalyze the French economy by increasing business-friendly incentives. Furthermore, the ongoing protests by the yellow vests inside France, which underscore the economic frustration among many French people, should hamper the growth picture further. And across the Channel, the UK may or may not struggle with Brexit, and while the eventual outcome could be positive, strains during any transition are likely.

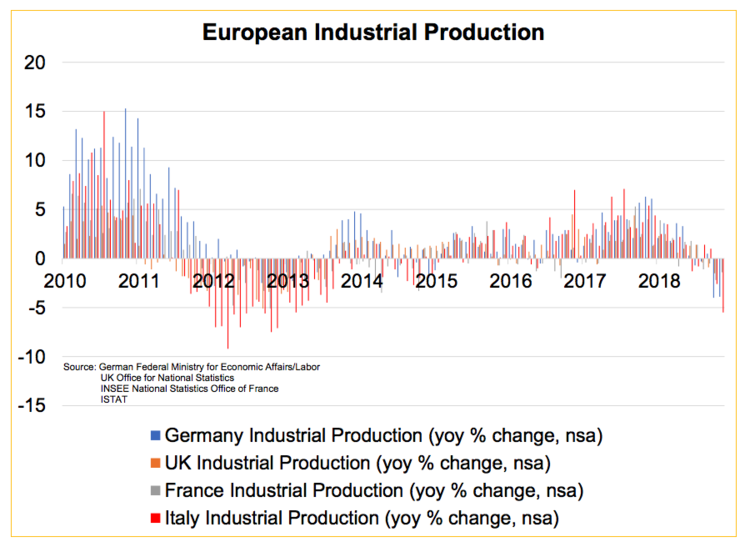

The sluggish GDP data in Europe is supported by poor industrial production, which has been declining in Italy, the UK, France and Germany since late 2017. In sum, the four leading European economies appear to be simultaneously entering a state of economic distress.

Figure 3: European Industrial Production.

We believe that the current downcycle in Europe is a harbinger of something much bigger: a secular economic decline in Europe driven by lackluster performance by Germany due to a series of poor policy decisions and even outright policy failures. Germany is yet again set to become the sick man of Europe. In our view, like 20 years ago when the German economy was a laggard, the problems appear to be self-inflicted: a combination of encrusted labor markets with well-intentioned but costly and failing reforms.

Energy

Energy policy is one of Germany’s most significant policy failures. Following the Fukushima nuclear disaster of 2011, Chancellor Merkel single-handedly flip-flopped on longstanding conservative support for nuclear energy and announced the phasing out of all of Germany’s nuclear reactors by 2022. To some people today, it is understood that this radical shift was less motivated by fears of a nuclear disaster, and more so by fears of political gains by the Green Party, which scored significant regional electoral victories in the immediate aftermath of Fukushima. Merkel’s strategy worked well for her, allowing her to hold on to power. Unfortunately, it worked less well for the users of electric energy and the German economy at large and is an example of well-intentioned government policy gone bad.

Estimated annual subsidies of nearly 15 to 40 billion Euros, according to Clean Energy Wire, may be required to implement this policy failure. While industrial users of electricity have their consumption subsidized, it may not be enough to fully offset the pincreases wrought by the replacement of nuclear power by more expensive alternatives, renewables in particular. BASF’s ex-CEO Kurt Bock, who has been a vocal critic of high energy prices in Germany, curtailed his company’s investments there, despite electricity subsidies available to industrial users.

At the same time, households are bearing the brunt of the burden because retail electricity prices are used to finance the subsidies to industrial users and now pay some of the highest electricity prices in the world. Less affluent households see their power cut off for non-payment of electricity bills at a record rate. And one nuclear power plant that had been completed only recently operated for only 13 months before being dismantled, costing energy company RWE losses of at least five billion Euros.

Policy planners in the German government were hoping that wind and solar energy would replace the production capacity lost from nuclear reactors. A massive buildout of these technologies has dotted the country’s landscape, particularly in the north, with windmills. At a nominal capacity of over 100GWh, equivalent to five Chinese Three Gorges Dams, wind and solar now exceed peak demand. But only on paper.

Because they work only when the wind blows or the sun shines, their contribution to energy production is highly variable. The unreliability of renewables has meant that an equal capacity of conventional coal and gas power plants had to be built, effectively doubling the amount of capital needed to produce a given amount of electricity and boosting electricity costs.

The variability of energy production by renewables poses serious challenges to the operators of the electricity grid. Widespread blackouts can be avoided only by shutting off electricity to power users such as aluminum furnaces or glass manufacturers. 78 such mini-blackouts occurred last year. Unreliable electricity coupled with high costs is something found otherwise in developing countries, and this may be the direction in which the German economy is heading as the energy policy failure is beginning to lead to a slow, and perhaps certain deindustrialization.

Chemical giant BASF is the most vocal and prominent company so far to have announced its intention to reduce investments in plants in Germany – other companies have taken this decision quietly without much fanfare, such as SGL Carbon, which built its latest carbon fiber factory in the United States instead of Germany.

Excessive government spending, high taxes

Although uninhibited government spending is far from being a uniquely German problem, it has become particularly problematic as a result of the relatively strong performance of the German economy during the last decade or so.

Since Merkel’s accession to power in 2005, tax revenue has increased by 78%, yet many core government activities suffer from acute underfunding. The army’s desolate condition has been well documented elsewhere – not a single functioning submarine, pilots who cannot complete their required minimum flight hours due to a large number of aircraft permanently grounded for service, and even the fleet of aircraft shuttling government ministers around the world tends to break down during state visits to remote locations. Even Angela Merkel arrived late to the G20 summit in Argentina late last year after her aircraft experienced technical difficulties. Netjets might go out of business with such a track record. Although infrastructure is still generally in excellent condition, maintenance has been delayed due to lack of funds so that future deterioration has become inevitable.

Where did all the money go? Government debt declined by approximately 5% between 2012 and 2017 but still exceeds pre-crisis levels by almost one third. Spending categories with the largest increases are personnel and material costs. So ever more bureaucrats need ever more offices.

A good example is the Chancellery in Berlin: Angela Merkel’s staff has increased from 400 to 750, so only 18 years after its completion, Berlin’s Chancellery has become too small. An extension with 400 new offices will cost 460 million Euros – more than one million per office. At that cost we can only hope that the offices will be stately and representative, although it is more likely that they will look dull and dreary as government offices typically do. In any case, the decade-long timeline until completion leaves plenty of room for cost overruns. Further spending increases are seemingly guaranteed, as public sector unions have negotiated an 8% raise.

The irony about the increase of tax revenue from less than 20% to over 23% of GDP during Merkel’s term in office is that she campaigned on an increase in value added taxes to be offset by a reduction in income taxes. Once in power, value added taxes went up as promised, as did a host of other taxes, particularly taxes on capital; the promised reduction in income taxes was shelved. Tax cuts were last implemented nearly 20 years ago by former Chancellor Schroeder’s left-leaning government.

Ever more bureaucrats also means that they need ever more areas to regulate. Despite steady population growth, the city administration in Berlin has reduced the number of housing permits issued, and it has lengthened the time it takes to receive a permit. Residential housing in Berlin can now take ten years from concept to completion. To appease an angry public, the local government talks about expropriating residential REITs without explaining how that would increase the stock of housing.

Social spending largesse

Not only in phasing out nuclear energy did Merkel adopt positions that were previously held only by her coalition partner SPD, following the 2017 election, she wholeheartedly allowed Social Democratic ministers to implement numerous expensive programs, the costs of which have saddled taxpayers with enormous unfunded liabilities. For example, the extension of pension benefits to stay-at-home mothers who raise children but make no pension contributions will cost billions, with even higher costs for decades after that. This follows a 2013 decision to offer free childcare to all.

To the chagrin of Social Democrats, none of these new programs have translated into electoral benefits for them. The SPD’s standing in the polls today is the lowest ever. Were elections held tomorrow, they would underperform their lowest election result ever.

In a desperate attempt to stem its decline, the current SPD leadership now tries to do more of what has failed before: more spending. Given Merkel’s record of appeasing her coalition partner, there is a good chance that taxpayers will be saddled with even more liabilities.

Political uncertainty

Merkel’s decision not to run again in the 2021 election has turned her into a lame duck chancellor and introduces significant political uncertainty. It is surprising that Merkel chose this route due to the risk of recreating the atmosphere of inaction that permeated the last years of the Helmut Kohl era during the late 1990s, who was her mentor and whose office ended when he lost an election after voters grew tired of him. Arguably, her decision to retire at the time of the election was driven by a desire to avoid such an embarrassing election loss. However, two years of stalemate will mean that her departure will likely have a negative tone.

Another sobering aspect of Merkel’s departure plan has been the appointment of her successor. Normally, a successor would be expected to break with the Merkel era. However, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer (“AKK”) is perceived to be Merkel’s mini-me, who will perpetuate Merkel’s overall policies, including the politically unpopular aspects of energy policy and migration. Friedrich Merz, a free marketeer with a deeper understanding of economic policy, deregulation and taxes, lost narrowly. We believe, however, that there is a chance that he will be involved in a future government and potentially even stage a challenge to AKK, although that may not happen until after the 2021 election. AKK’s economic thinking does not appear growth-friendly, namely her support for an increase in the top individual income tax rate from 42% to 53% and her opposition to inflation-indexing of tax rate thresholds, leading to creeping tax increases.

Malaise set to worsen

After a decade of ultra-low interest rates, the German economy that helped to keep Europe going is not only slowing but may be in a much more precarious position than before the financial crisis. Therefore, the real risk today is not just a cyclical recession, but a prolonged downturn. Overcoming a decade of significant policy errors is not going to be achieved during the normal duration of a recession, much less so if you also need to overcome a decade of misinvestment due to low interest rates and onerous tax policies.

The impact of an emergent economic downturn on employment is likely to be muted at first because companies will be reluctant to fire workers. This is partly the effect of stringent employment laws that make it difficult to adjust the size of the workforce to changes in production, and partly companies’ recent experience of extremely difficult hiring conditions.

While the German economy is flooded with low-skilled and unskilled workers, partly as a result of recent migratory trends, qualified workers with strong technical backgrounds are scarce and companies were unable to fill many such jobs during the recent boom. As a result, many companies will keep workers on the payroll and hope to ride out the recession. This favorable employment picture in the midst of a recession will likely reduce political pressure for much-needed reforms and exacerbate problems in the future.

The most likely response by governments to reduced tax and social security receipts will be tax increases, rather than reductions in spending or aggressive tax cuts on investment capital. If you want less of something, tax it. As such, tax increases will only exacerbate the slowdown in economic activity through a decline in investment. Although the nominal tax rate on capital in Germany is 25%, only five points higher than in the U.S., this rises to almost 30% once various surcharges are included. Moreover, deductibility of losses has been curtailed sharply in the name of tax justice to ensure that companies pay a minimum tax rate, which reduces the attractiveness of investments that are profitable in the long run but are lossmaking early on.

Not surprisingly, investment is limited in many cases to saving projects in established firms. While there has been a mini-boom in internet and technology firms, it is nowhere near a level that you would expect from the fourth largest economy in the world. Germany is lagging far behind technology leaders U.S.A. and China. Nothing illustrates this lag better than the opening of offices in Silicon Valley by the few German technology and internet companies who end up succeeding and want to gain scale. They desire to tap into venture capital and the technology scene in general, which is woefully lacking inside Germany. A study by PwC of the Global 100 Software Leaders lists only five German companies among the top 100 by revenue, and we would question whether Siemens should even be counted as a software company so that the real share is a measly four out of 99.

The Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW) sees Germany in a much weaker economic position than prior to the 2008 financial crisis because of deficiencies in infrastructure spending and a lack of corporate tax reform since the government of Chancellor Schröder nearly two decades ago. IfW warns that bureaucracy has increased and with trade partners from Europe to China experiencing an economic slowdown, export growth will not likely bail out the economy this time. We would add that the U.S. is going to be the beneficiary of the corporate tax stalemate thanks to U.S. corporate tax rates that are now in line with Switzerland, the U.K. and Eastern Europe.

Germany’s economy remains rooted in old tech such as chemicals, industrial equipment and automobiles. While these industries have generated substantial trade surpluses over the last decade, this has not led to a corresponding increase in household wealth. Today Germans are, on average, less wealthy than Italians, Spaniards or the French. In our view, an important factor behind this discrepancy is the low rate of homeownership, and also the propensity to invest savings in assets with low volatility, mainly low-yielding savings accounts and life insurance policies, which prevents savers from accumulating wealth. Even worse, negative interest rates have reduced the wealth of citizens while facilitating excessive government consumption.

While it is true that many of the problems faced by the German economy are faced by other economies elsewhere in the world, too, it is the ignorance by the political leadership of the origins of the strong economic performance that is unique. Wealth and growth are taken for granted, capitalism is considered evil and must be contained. The United States also suffers from a terribly inefficient public sector, but a combination of low tax rates, entrepreneurship and readily available capital for new ventures offset many of these problems.

As a consequence, we believe that Europe will return to a state of Eurosclerosis in the decade of 2020, triggered by the inability of Germany to continue to act as the growth engine for the continent. Continued problems in the European periphery from Italy to Greece are likely to add to the downward economic pressure.

Investment Implications of Eurosclerosis

For investors, Euroscelrosis raises the question of portfolio implications. The old dogma of not investing in European companies and instead investing in U.S. firms no longer works due to globalization. For example, Roche had only 24% of its 2018 sales in Europe, while Bristol-Myers Squibb achieved a similar percentage of its sales there. Substituting European pharma Roche with an investment in U.S.-based Bristol-Myers will in no way reduce portfolio exposure to the European economy. This is a practical consequence of globalization: everyone has global exposure. Therefore, traditional large and mega cap investment strategies offer poor prospects for reducing portfolio exposure to Europe by divesting Europe-based stocks.

In our opinion, the impact of Eurosclerosis is more benign, potentially even favorable for event-driven investments. In a weak economy the pressure to optimize corporate structures is likely to increase, in particular when European companies benchmark themselves against U.S. firms that have gone through a decade of mergers and splits. Therefore, opportunities in merger arbitrage and spin-offs should increase, while simultaneously a growing number of distressed opportunities will arise. While Eurosclerosis will be difficult for traditional investment strategies we believe that it will present many opportunities for event-driven investors.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2ZQTbnX Tyler Durden