Authored by Tad Rivelle via TCW.com,

Ask an ornithologist why birds fly south in the winter. If the answer is “instinct”, then you actually received no answer at all. Saying birds fly south because it is “instinctive” provides zero insight into the governing mechanism or complexities of the behavior. Labeling an action is not the same as understanding the action.

Latter day central bankers – essentially politicians with PhDs – have furthered a mythology that by dialing one single policy rate higher or lower, that a trifecta of goals can be accomplished: steady growth, modest inflation, and “balanced” financial markets. Really, all that? But I guess if you are the institution that wields the interest rate hammer, every economic problem looks like a nail. But calling a policy “stimulative” does not necessarily make it so, nor is it even exactly clear what is being stimulated. The economy in aggregate is not a machine and the humans that are the soul of the system will not respond on cue just because the macro plan says that they should.

In my first year out of the cloistered halls of my alma mater, I got a schooling in the governing force of real-world incentives by the engineer across the hall. While he had less formal education than I (no four year degree), he grew up on a farm near Guyman, Oklahoma which, at least in his case, accorded him an honorary PhD in logic and commonsense.

The topic du jour (this was 1981) was that of the then recently repealed price controls on interstate shipments of natural gas. He explained that the income from his family’s farm derived mostly from extracting the gas that was below the ground rather than from harvesting the wheat which grew on top of it. During the time referenced, the catch was that any gas extracted could only be sold at the artificially low, Federally controlled price, a value well below that of the “true” North American price for gas. And, while gas extraction was still profitable, the farm managers evidently didn’t feel like they should be coerced into delivering their gas below the true market price. The result? The production valves were turned to the “off” position as the farm managers elected to wait out that period of “fiat” pricing of natural gas.

So, price controls turn out to be bad policy. Who knew? Still, an academic might throw his hands up and rail at the confounded irrationality of the farm managers. Didn’t they get it? Marginal revenue from selling the gas exceeded the marginal cost of production, so no one was “supposed” to shut the wells down. And, yet, production was shuttered. In the end, it was not the economist’s “logic” but rather the unobservable judgment call by the farm managers that called the tune. The real, live, breathing humans exercised their subjective judgment that production should halt even as a methodology based on objective factors said otherwise. And this illustrates the point: just because the economist believes he can model it, describe it, categorize it, does not mean that he can understand it or predict it. Tweak some dial, and you might get a certain set of first order responses. These responses will spawn a round of second order responses, and so on. The results will depend on a myriad of judgment calls which might—or might not—aggregate to some facsimile of what the central banker’s model says ought to happen. And, did anyone happen to say anything about costs? Economics is predicated on the idea that resources are always limited and to believe in a policy that brings benefits without associated costs is to see the world as populated by rainbows and unicorns.

What’s obvious on the farm is frustratingly murky to the Fed and its overseas kin. Central banking insists that interest rates are mere tools to be employed in the service of optimizing macroeconomic outcomes. But interest rates are prices. When the Fed places its thumbs on the price of credit, the natural balance between the needs of the borrower and the wants of the lender are disturbed. Perhaps this is why the central banker’s favorite descriptor for rate policy is to label it “stimulative.” No one could be against that! But is it fair to say that everyone’s outcome is being proportionately “stimulated?” Are there no costs associated with “stimulus?” And, what exactly do we mean when we say the economy is being “stimulated?” What activities are being facilitated that wouldn’t have happened otherwise?

Thought experiment: suppose by “stimulative” we mean that a thousand wells get drilled that wouldn’t have otherwise. The drilling of these holes was presumptively enabled by the artificially cheap credit that was used to finance the labor and buy the drilling equipment. Mainstream economic logic says this is all good: more wells drilled means more employment so more spending, and as everyone’s spending is someone else’s income, stimulus is the gift that keeps on giving. Ah, stimulus!

Now consider: if those wells strike it rich, new economic production is unleashed and a virtuous cycle has actually commenced. The result would be more GDP now and more GDP later. But, what if those artificially induced wells turn out to be all dry? No harm, no foul? Obviously, not. Those that provided the credit to drill the wells find their notes or loans to be worthless. In that event the bill for the supposedly “free lunch” of cheap credit at last arrives on the balance sheet of those who lent the funds. Instead of a miraculous growth tonic, “stimulus”, in this event, turns out to be little more than an intertemporal transfer of wealth away from the lender. The GDP that was initially created is now canceled out. Oh well, easy come, easy go.

Evidently, “stimulus” can mean very different things and can bring very differing results. How can the economist properly calibrate his “stimulus” model without the foreknowledge as to how many of these artificially induced wells will come up gushers and how many dry? Wait! You mean you can’t actually know what the costs and benefits of a policy are until after the fact? Great Scot! But that would mean that the long-term costs and benefits of “stimulus” can’t be tallied before the fact! And, if a mathematical model can’t predict how a flesh and bones farm manager will respond to price controls, how can we buy the notion that a central bank could predict the actions and interactions of many millions in response to a level or change in a fiat interest rate?

So, maybe, just maybe, when the Fed sees that credit creation is organically slowing, perhaps it ought to calculate that the slowing is for a good reason: possibly well drilling has grown expensive or perhaps there are few promising places to drill, or perhaps the lenders judge there to be too much already lent to the drillers. But rather than defer to the true experts, the central banker assesses a slowing, any slowing, of credit to be problematic. And, as less credit means less drilling means more “slack resource,” more “stimulus” is called for, whatever that means exactly. The central planner knows best.

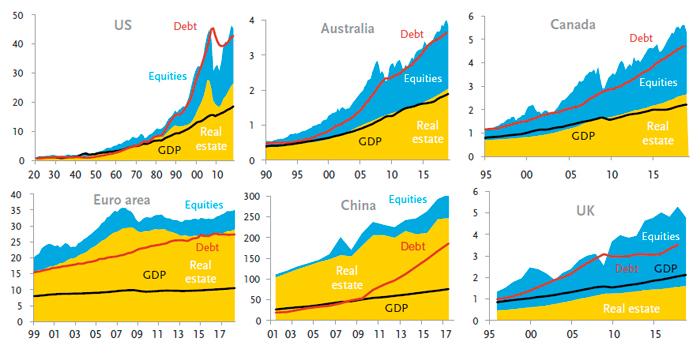

Do we have any way to assess what the fruits of “stimulus” have been thus far? Perhaps the following charts provide some help:

Source: Citi, BIS, national central banks StatCan, WFE, Savills.

US and China are at constant 2009 $ and RMB, others are nominal. Uses household holdings of real estate as proxy where no direct market cap available.

Let’s ask ourselves: has the credit this cycle been used to drill productive wells, metaphorically speaking? Measured by income generated, it doesn’t look that way to me! Evidently, too much credit has been employed in “stimulating” asset prices. Alas, if asset prices “correct”, lots of debt will be written down, and what was understood as “stimulus” will be re-classified as mal-investments.

No household nor business can stay on a path of forever rising debt to income, nor can any society in aggregate. More and more stimulus – leverage – is ultimately a bridge to nowhere. Investors would do well to recall the down on the farm wisdom of Stein’s law: if it can’t go on forever, it won’t.

* * *

Tad Rivelle is Chief Investment Officer, Fixed Income, overseeing over $165 billion in fixed income assets, including over $85 billion of fixed income mutual fund assets under the TCW Funds and MetWest Funds brands.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2M0DLKE Tyler Durden