For the past year, one of the points of biggest contention among economists and traders is that despite what is now a 1+ year trade war with China, inflation due to higher tariffs has been strangely missing, with some claiming that the goods targeted in previous tariff rounds were either not “consumer” enough, or simply had more affordable substitutes from other, non-Chinese supply chains, allowing consumers to avoid having higher prices passed upon them.

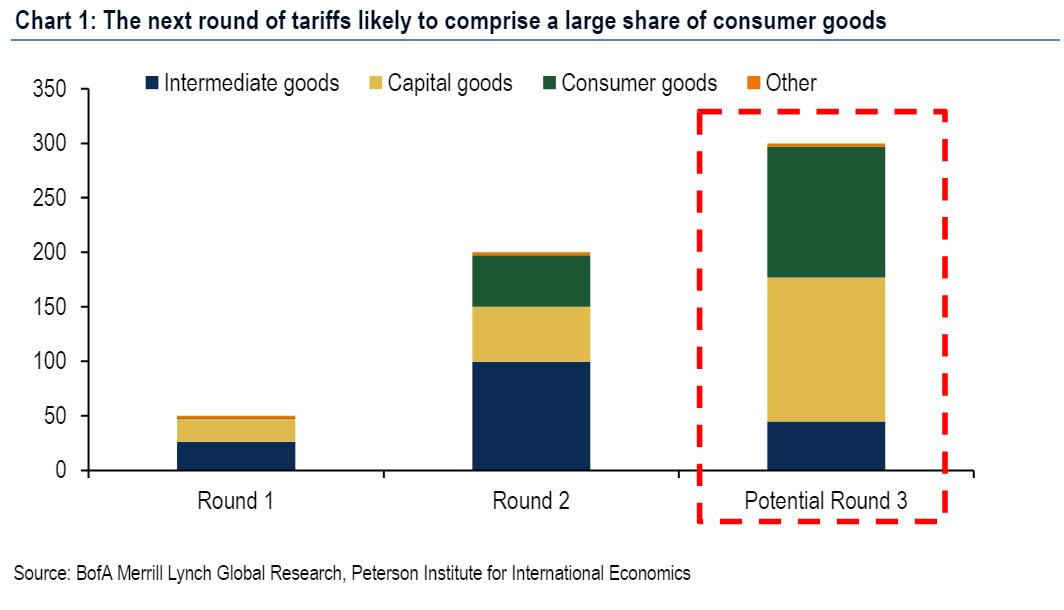

While this may be correct, everything is about to change, because as Bank of America team of economists writes, Trump’s latest tariff announcement from last Thursday, when the president shockingly unveiled 10% tariffs on $300BN in Chinese imports starting September 1, “is a major escalation.” The reason for this is that past measures had mostly avoided consumer goods. By contrast, the threatened tariffs would cover $120bn of consumer goods, out of $300bn in total, and since BofA expects the tariffs to be implemented, either on schedule or later this year, the period of dormant trade war inflation is about to end with a bang, not a whimper.

What happened?

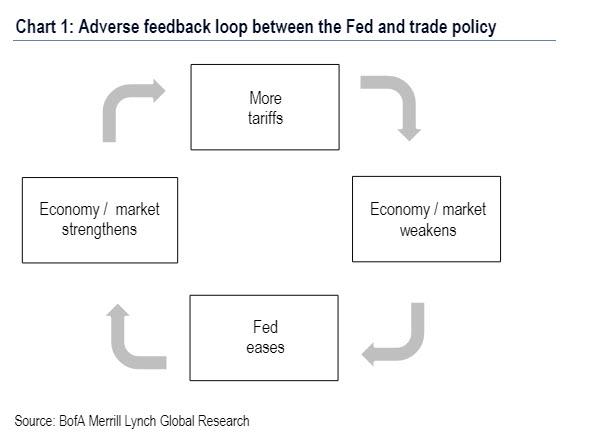

For those who were blissfully on holiday last week and missed what was without doubt the most insane 72 hours in capital markets in 2019, on Thursday President Trump announced that the US will impose 10% tariffs on all Chinese goods that were excluded from earlier measures. The announcement reportedly came soon after the President was briefed on Treasury Secretary Mnuchin and Trade Representative Lighthizer’s negotiations in Shanghai on Tuesday (July 30). There was also a press report on Wednesday arguing that China was intentionally slow-walking the negotiations in the hope of getting a better deal. It is probably not a coincidence that the President stated after announcing the tariffs that Chinese President Xi was not moving fast enough. Most importantly, and as we predicted just hours before Trump’s “shock” announcement, Bank of America does not think it is a coincidence that the tariffs were announced the day after the Fed cut rates and ended quantitative tightening. Indeed, as we noted yesterday, as a result of the phrasing in the latest FOMC statement which bizarrely ushered in the first easing cycle in 12 years not due to domestic but international considerations, the Fed is now effectively underwriting Trump’s trade war, as shown in the following chart (read more here).

Was Trump’s announcement a negotiating tactic?

Most likely, yes… but as BofA’s Aditya Bhave notes, “that does not mean it is a bluff. We have seen this movie before. President Trump has implemented every measure against China that he has threatened, albeit sometimes after a delay. Prior announcements were probably also meant to up the ante on China, but China has consistently refused to buckle under pressure. Why should this time be different?”

Why indeed, especially if with every incremental escalation in the trade war, the Fed is forced to cut rates further, precisely as Trump demands.

What does this mean for the outlook?

From the perspective of Bank of America, the pattern of US protectionist measures pointed to a desire to avoid tariffs on consumer products due to concern about “sticker shock” for consumers. This was arguably why a large share of consumer goods imports from China were excluded from earlier rounds of tariffs, and why tariffs on autos and parts have repeatedly been threatened but not implemented.

But, as Bhave writes, “the latest announcement is a game changer. About $120bn of the imports covered by the threatened tariffs are consumer goods, compared to less than $50bn in total in the earlier rounds.”

And since the “sticker shock” concern does not appear to be as important for Trump as was previously thought – perhaps as a result of the stock market hitting fresh all time highs, which in Trump’s mind offsets “slightly” higher prices, BofA now expects the US to follow through on the President’s threat and implement the 10% tariffs. In terms of timing, there may be a small delay, particularly if there is a big selloff in equities in August (which however will only force the Fed to cut sooner, thus boosting prices), but in general, the bank is confident that the tariffs will go into effect this year.

This also means that in terms of further escalation in the trade war, “all options are now on the table” even though the baseline assumption is that there will be only modest additional measures on various fronts. However, BofA does see substantial risk that the 10% tariff could get increased to 25%. At that point there would be 25% tariffs on all Chinese imports; Additionally, there is also a high risk of tariffs on imports of autos and parts from outside North America (with South Korea also likely getting an exemption), particularly as such tariffs would incentivize producers to meet the USMCA’s stricter local-content rules.

In keeping with the “more trade wars, more rate cuts” dynamic, there could also be measures against other countries that are benefiting from shifting supply chains, have large and growing trade surpluses with the US, or are allowing Chinese goods to evade US tariffs via trans-shipment. The first target among such countries suggested by BofA, would likely be Vietnam, against whom President Trump has already threatened action. Whether major additional measures get implemented will ultimately depend on political, economic and market incentives.

Impact on the presidential elections.

The US-China trade war is unlikely to de-escalate going into the 2020 Presidential elections, according to BofA. Indeed, the escalation going into the 2018 midterms suggests that “the Trump administration views getting tough on China as an effective strategy in the polls” according to BofA. Meanwhile, escaping the tit-for-tat loop of more tariffs has become next to impossible as there is growing bi-partisan support for a more confrontational policy stance vis-à-vis China because it is a rising geopolitical rival with a non-market economy.

Regarding other fronts of the trade war, it is a closer call, according to the BofA economists. On the one hand, protectionism has been an important part of the Trump agenda from day one. China has been the most prominent target of the President’s critiques, but it has not been the only one. This is why we see risks of measures against other countries and sectors. On the other hand, there is not as much political support for other protectionist policies: China is “special.” The Trump administration also appears to have come around to the view that it is best to fight one battle at a time. Unless there is at least a lasting ceasefire with China, there might not be sufficient bandwidth for other large measures.

A Policy Collar Put

The other key determinant of the future path of the trade war as observed by BofA, will likely be the state of the economy and the markets. After the G-20 meetings, the bank – among many others – cited the risk that the Fed’s dovish turn was emboldening the Trump administration to keep escalating the trade war. This premise was that the markets and the economy were stuck in a “policy collar”, between a very accommodative Fed (the “Fed put”) and the uncertainty shock from the trade war (the “Trump call”).

Of course, this week’s events only confirmed this view (see feedback loop chart above). This is what happened:

- On Wednesday, Fed Chair Powell said that concerns about the trade war were one reason for the Fed’s 25bp rate cut.

- On Thursday, President Trump escalated the trade war further.

- The markets responded by pricing in substantially more Fed accommodation.

- Between the time of the announcement and close of business on Thursday (a little over 3.5 hours), the 2-year Treasury yield fell by almost 8bp and the markets priced in about 10bp of additional Fed rate cuts by year-end.

As a result, life for the Fed has become far harder in two ways:

1. It will probably be trying to offset an even larger negative economic shock. But even if that shock does not materialize, the rally in rates means that the Fed will have to use up more ammunition if it wants to meet market expectations and avoid financial tightening. The risk is of a perverse feedback loop in which trade-war escalation keeps offsetting Fed easing, leaving the Fed with very little ammunition to fight the next recession, while the economy remains relatively soft.

What’s worse is that the game theoretical equilibrium that has emerged for the trade war is one of “no pain, no deal.” As we mentioned above, a substantial equity market correction could delay the threatened tariffs. By the same measure, it could disincentivize further escalation. Alas, so far the market refuses to even consider a “substantial correction” – while the S&P 500 did sell off by almost 2% on Thursday after the tariffs were announced, this is a negligible drop from an all time high in the S&P above 3,000. As a result, and given that markets were at all-time highs just a few days earlier, BofA believes that it will probably take at least a market correction (i.e., a 10% decline) to move the needle on trade policy.

2. A shock to consumer spending and confidence could also have a similar impact. So far the US consumer has remained on solid footing because of the strength of the labor market. Even though academic research suggests that the cost of the tariffs has been almost entirely passed on to consumers, confidence has held up. This is likely because the tariffs were mostly on intermediate goods rather than final goods, and so their effects were obfuscated.

That could change with the latest threatened tariffs, which as mentioned above cover $120bn in consumer goods. Most of these goods are electronics-cell phones, laptops and tablets-whose prices are very visible. But the shock to prices will ultimately depend on the renminbi, which is already down almost 10% since the start of the US protectionist push last spring. If the PBoC allows another leg of depreciation, letting USDCNY break above 7, the FX move might largely offset the impact of the tariffs.

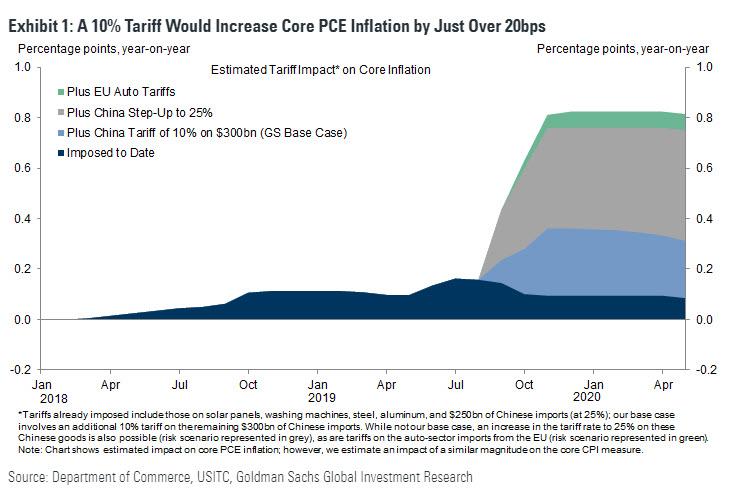

And speaking of a sudden inflation spike, here we refer to a recent Goldman Sachs report which noted that the bank’s economic forecast had already assumed a 10% tariff on $300bn of imports starting in September; as a result, the bank expects these tariffs, if implemented, would increase core PCE inflation by slightly more than 20bps by year-end. And while Goldman’s baseline forecast does not assume that tariffs rise from 10% to 25% on the $300bn just announced, nor does it assume tariffs on EU auto imports, though both are risks. Indeed, as shown in the chart below, even without a full-blown trade war escalation consumer inflation is about to get much hotter. However, should the tariffs step up to 25%, and if Trump implements EU auto tariffs, watch as inflation explodes higher.

And speaking of the economy, Goldman estimates a GDP hit from the 10% tariff on $300bn of China imports of 0.1-0.2%, on top of a 0.2% hit from the tariffs imposed to date. This means that the combined GDP drag would rise to 0.5-0.6% if the tariff rate on $300bn of China imports were raised to 25%, and to 0.7% if 25% tariffs were imposed on EU auto imports. In other words, prepare for the most violent stagflationary episode in decades, one which Powell may simply resign instead of deciding to hike rates to address.

Unintended consequences

Of course, nobody can predict all the possible adverse outcomes from an escalating trade war, especially now that China has its own geopolitical row with Hong Kong to manage: as BofA notes, a conflict of the magnitude of the US-China trade war “is bound to have far-reaching, unintended consequences.” Most importantly, it could extend ongoing global monetary easing. About half of the central banks that we cover have cut rates this year, and many more cuts are likely in the pipeline as further escalation in the trade war likely leads to an even weaker outlook for global (particularly Chinese) demand.

Speaking of pipelines, there could be major implications for oil for two reasons. First, weaker global demand would likely weigh on oil prices. Second, there is now a greater risk that China will decide not to comply with the US oil sanctions against Iran. This would ease global supply conditions, leading prices even lower. Brent was down more than 3% on Thursday after the tariff announcement. This could result in a further deflationary impulse across the core inflation supply chains, which accelerates the Fed’s rate cutting schedule.

Indeed, as BofA points out, “a big drop in oil prices would suppress inflation expectations, making it even harder for the major developed-market central banks to reach their inflation targets. Again, this would mean lower global policy rates, which in turn would imply that Fed easing might not have much impact on the dollar.”

Meanwhile, Trump’s frustration with the strength of the dollar could push his Administration to “retaliate” by intervening in FX markets or imposing tariffs on countries whose currencies are deemed to be too weak, or as BofA puts it, “a tangled web indeed.”

* * *

Finally, a word on Brexit. So far it appears that the BoE has attempted to hold the line on cuts ahead of the October 31 deadline. Will the latest trade escalation push the BoE over the line into talking about rate cuts? If so, the resulting financial accommodation might make a no-deal Brexit slightly less painful and therefore slightly more likely. There might not be enough time for this dynamic to play out. But the feedback loop is very familiar: one only needs to glance across the pond to understand it.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2YFwxxC Tyler Durden