Ten days ago, we reported that in the aftermath of Trump’s unexpected concession when the US unilaterally decided to delay the imposition of tariffs on Chinese consumer products from September 1 to December 15, China mocked Trump’s act as “proof he is losing the trade war.”

Today, Goldman confirms as much, and points out that in a paradoxical twist, it was Trump’s delay that may have made trade war with China even more complicated. In a note discussing China’s retaliatory tariffs, the bank’s China economist Yu Song writes that “the recent US decision to delay some tariffs could even paradoxically prolong the trade war since it has been seen as a sign of weakness, at least by some in China, and could make the Chinese government less willing to soften its stance to reach a compromise.”

Of course, this is a two way street, because as we said on August 13,” what is likely is that any widespread shift in sentiment that Trump retreated and waved a white flag of surrender, could very quickly undo the tariff delay as the last thing Trump wants, is to be seen as weak and ineffectual, or his trade war strategy as inefficient, not by his base, and certainly not by his opponent, China.“

Today, all these concerns came true. And while we doubt that Trump will accelerate the delayed tariffs – after all he doesn’t want an inflationary spike just in time for Christmas as Chinese consumer good import prices soar – the hope of any trade deal before the November 2020 election is now dead and buried.

Here is the full Goldman note:

China retaliates by imposing additional tariffs on US imports

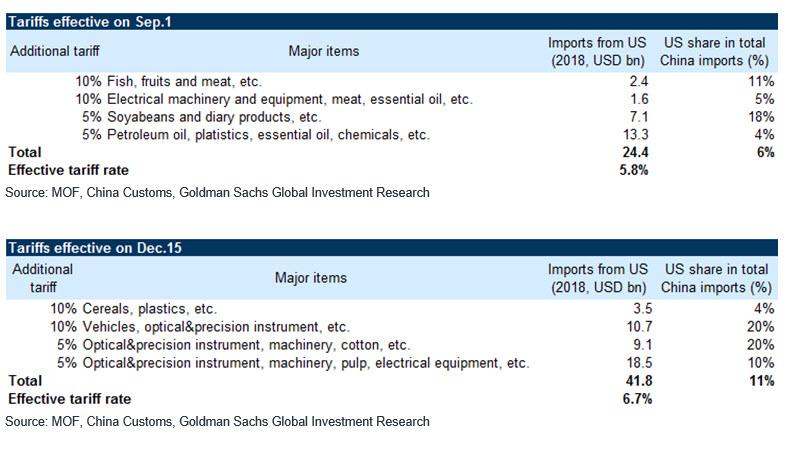

Ministry of Finance in China announced Friday evening that it will (1) resume the import duties on US automobile components which have been paused since December last year and (2) impose additional tariffs on over 5,000 items of US products with total annual Chinese imports of $75bn. Similar to US tariffs, the products are divided into two lists. The first list (effective on September 1) includes soyabeans and petroleum oil (5% additional tariffs) as well as some seafoods, fruits and meats (10% additional tariffs). The second list (effective on December 15) includes cereals and vehicles (10% additional tariffs), as well as optical and precision instruments (5% additional tariffs).

This is a direct retaliation to the latest round of tariffs by the Trump administration. Since the trade war started last year China has retaliated each time after the US imposed tariffs. It could be argued that not doing anything in retaliation might be in the interests of the Chinese economy, but we believe this would be not acceptable politically. The government clearly indicated it would retaliate a number of times, so this action should not come as a surprise.

As in the past, the size of China’s retaliation is less than proportional to the US imposed tariffs. Technically, China could have retaliated proportionally by compensating for the smaller quantity of taxable imports by imposing an even higher level of tariffs. But this could lead to a further escalation of the trade war, and the negative impact of much higher tariffs on the Chinese economy is another consideration. The recent US decision to delay some tariffs could even paradoxically prolong the trade war since it has been seen as a sign of weakness, at least by some in China, and could make the Chinese government less willing to soften its stance to reach a compromise.

Given trade escalation, the weakness in recent activity data and the upcoming National anniversary, we believe there is a clear need to loosen policy more. The interbank rate has started to drift down after the LPR reform. There have been suggestions about raising the annual government bond issuance quota, which we believe is likely. Other administrative measures to boost investments will likely be taken too. The NDRC has indicated it is looking into measures to boost rural consumption, without giving details. In our view, only FX depreciation and property loosening will not be used in the near term because of concerns about market stability and the social impacts. But policy easing so far appears to be limited and risks to the short-term growth outlook look tilted to the downside.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/30v6Gu1 Tyler Durden