Morgan Stanley: The “Pain Trade” Is Not Higher

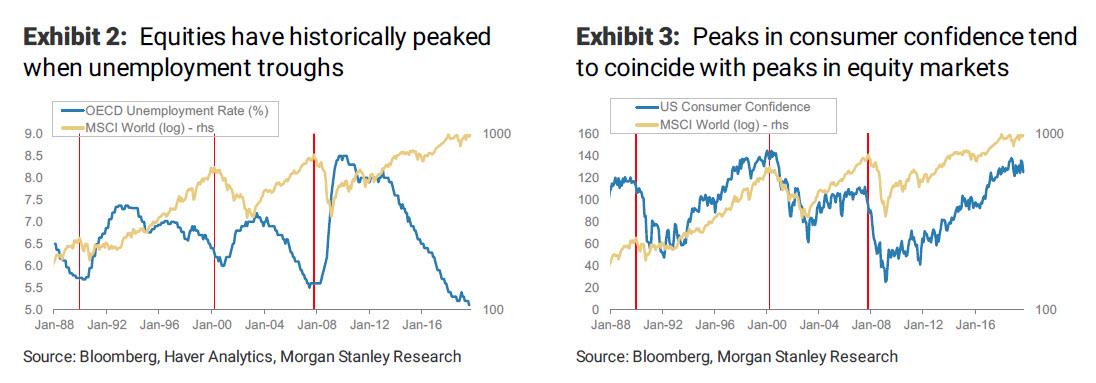

Whereas JPMorgan has been the unrelenting bull of this year’s 21% surge in the S&P500, Morgan Stanley has emerged as its bearish nemesis, and while JPM earlier today said its 2020 mid-year forecast of S&P 3,200 is doing so well, it could be hit as soon as this year, Morgan Stanley has once again doubled down on the bank’s bearish outlook, and in a report from its chief cross-asset strategist Andrew Sheets writes that it sees “a key divide. Some investors, like ourselves, remain cautious, focused on a variety of cyclical indicators that point to historically poor returns over the next 12-24 months.”

In framing the tensions, Sheets writes that “those with shorter-term investment horizons, are more optimistic” and notes that the optimists “cite two catalysts: i) Economic momentum, and PMIs, that are set to inflect; and ii) Already cautious sentiment means that growth concerns are already in the price.“

Why doesn’t Morgan Stanley agree with JPMorgan’s more optimistic take? Two reasons:

On the first issue, i.e., a rebound in economic momentum, Sheets points out the already large divide between asset prices (up) and US or global PMIs (down), as well as the fact that its US economists expect the next reading of ISM manufacturing PMI to see another decline. This PMI scenario does not bode well for risk assets.

However, it is the second point that is the emphasis of Sheets’ report, because as he writes, regarding sentiment three key factors have to be considered:

- Tactically, while optimism does appear modest, measures of risk-aversion (Morgan Stanley’s Global Risk Demand Index, the Put/Call Ratio, the VIX) have rallied sharply following last week’s developments on trade and Brexit.

- Strategically, the efficacy of investing based on ‘sentiment’ looks regime-dependent; it’s normal for investors to “get bearish in a bear market”. According to the strategist, “there’s above-average risk that we’re in such a regime.”

- Third, and final, while overall positioning is arguably modest, relative positioning in equity sector and style is extreme. The ‘pain trade’ isn’t higher, it’s rotation.

Everyone has heard the saying “climbing the wall of worry”, which is basically a less refined way of saying that cautious sentiment is one of the most compelling reasons to be bullish (i.e. “buy when there is blood on the streets”). Sheets, however, disagrees for the reasons listed below.

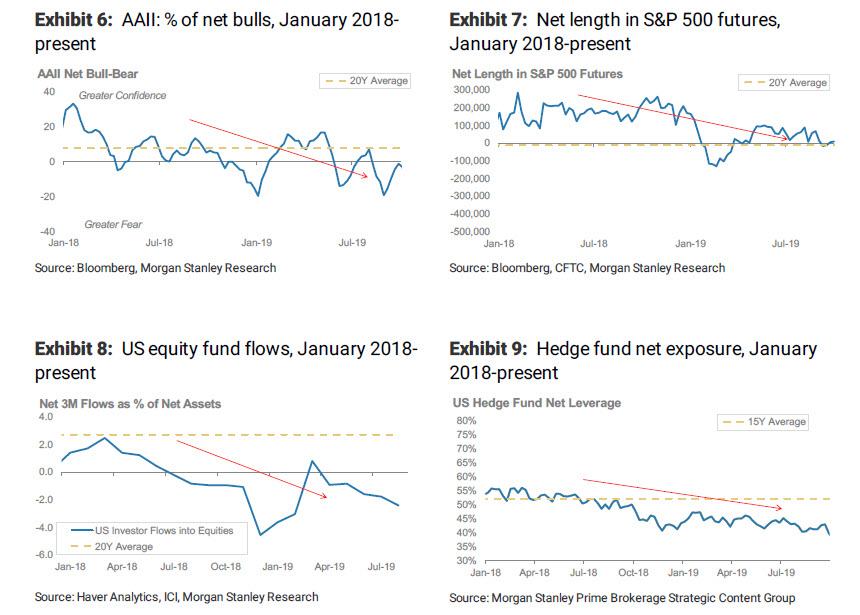

There are a variety of ways to measure investor sentiment. For better and worse, many tend to focus on the US market, the world’s largest. Sheets begins his discussion with four indicators that he often sees cited as indicators for investor caution or greed.

- AAII net bull-bear index: Per a weekly survey from the American Association of Individual Investors, this index shows the difference between those who are ‘bullish’ and ‘bearish’. The bank focuses on the four-week moving average to reduce noise.

- Net length in S&P 500 futures from CFTC: Lower net exposure would, in theory, suggest more investor caution.

- Equity fund flows from ICI: Weaker fund flows would, in theory, suggest more caution.

- Hedge fund net exposure from our Morgan Stanley Prime Brokerage desk

The charts below summarize these four sentiment indicators over the most recent 18-month period, and as Sheets points out, “none suggest a great deal of optimism over the last 18 months, and such pervasive caution for an extended period of time is frequently cited as a helpful factor for markets.”

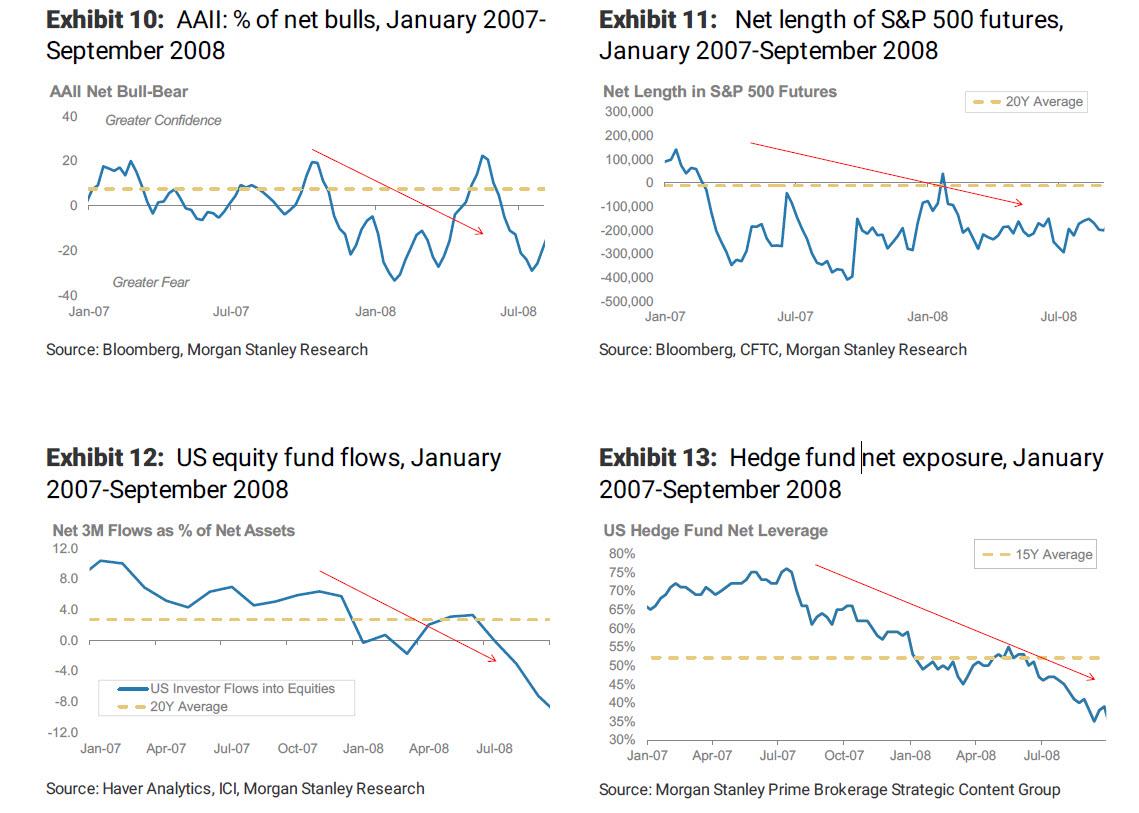

Yet whereas bulls will say the charts above are a clear indication to buy, one can easily present a counter argument. To wit, what happens if one looks at these measures over a different period – say the 18 months starting in January 2007: Similar to the charts above, these also saw below-average levels of sentiment over an extended period. But this wasn’t a signal to buy; it reflected investors (correctly) appreciating that the market environment was changing, for the worse.

Needless to say, anyone who used collapsing sentiment into the global financial crisis as a contrarian signal to buy was not very happy.

Fast forward to today, when “cautious” sentiment over the last 18 months hasn’t stopped global stocks (MSCI World) from falling over this time. This may be because that cautious sentiment was simply (correctly) responding to worsening market dynamics. And as shown above, 2007-08 saw a similar pattern, albeit with far more market weakness, which is to be expected: back then the Fed did not provide assurance it would step in any time there was a market spasm.

* * *

Another surprising finding: contrary to conventional wisdom, which holds that as of this moment most investors are skeptical and have limited exposure to risk assets, a proprietary Morgan Stanley indicator finds precisely the opposite.

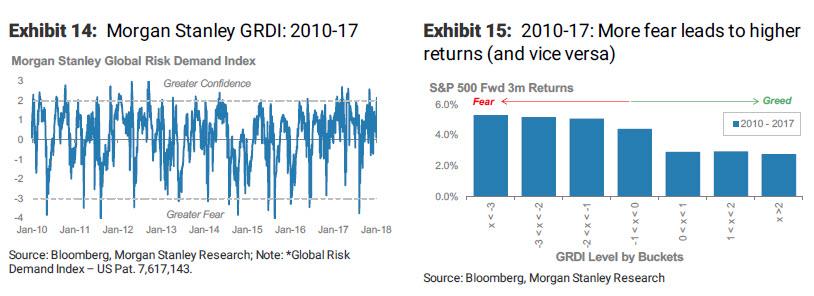

As Sheets writes, the idea that sentiment indicators can be regime-dependent can be seen in something Morgan Stanley cites frequently – the Morgan Stanley Global Risk Demand Index, created and run by the bank’s FX strategy team (STGRDI

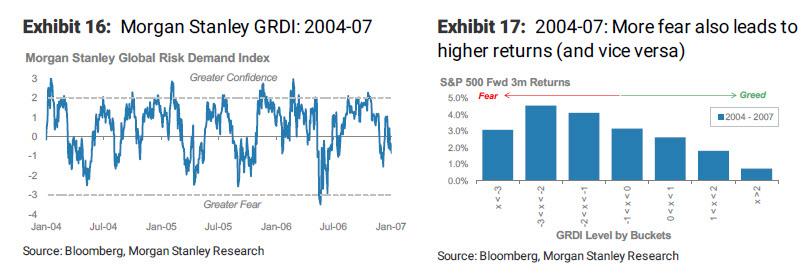

From 2010 to 2017, what one has been supposed to do with those signals has been pretty straightforward. ‘Greed’ often reflected good sell signals and ‘fear’ good times to buy, something we can quantify by looking at 3-month forward returns based on different levels of the index.

A similar pattern was observed in the bull market prior to this one, 2004-07. In both cases, this sentiment measure worked ‘as expected’ in a trending bull market, according to Morgan Stanley.

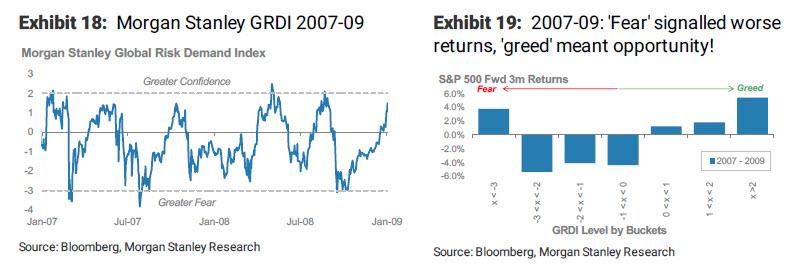

But GRDI’s ‘signal’ changed dramatically in the time between, specifically the bear market of 2007-08: Running the same analysis during that internal reveals that the forward performance picture is almost completely reversed from the two bull market periods.

Why has sentiment been less effective in a time of market stress? Simple: it’s normal for investors to get bearish in a bear market!

This brings us to one of the biggest variations in opinion between Morgan Stanley and JPM, which has been pounding the table on bearish sentiment as a key catalyst for further upside (to be fair, JPM has been bullish when sentiment is bullish, as it confirms their thesis, and has been ever more bullish when sentiment is bearish, when it serves as a bullish contrarian signal). Here, Morgan Stanley asks if sentiment measures could be facing another shift in regime that could reduce their efficacy? And answers: “We think the risk is high” largely as a result of the “relatively light positioning over the last 18 months” which hasn’t prevented what our MS’s house uber-bear, Michael Wilson, has coined the “unsatisfying bear market” back in April 2018, an extended period of choppy markets, frustrating for bulls and bears.

Meanwhile, the economic and cyclical risk looks above-average, with Morgan Stanley’s cycle model moving to ‘downturn’, itself a sign of a potentially different regime…

… and – what’s worse – investors are now facing a market with ~0% global earnings growth, falling margins, a flat yield curve, weak PMIs, weak commodity prices and defensive leadership, all things that are very different from the 2010-17 or 2004-07 regimes when sentiment indicators were most effective. All of this brings us to a conclusion which we have long believed is the right now, namely that…

The ‘pain trade’ isn’t higher

Framing the argument, agaion, Sheets writes that when discussing sentiment and positioning over the last 18 months, one often confronts the argument that, due to widespread caution, rising markets are actually more painful for investors than falling ones. While this is a small point, Morgan Stanley – and most rational traders – strongly disagree.

The main reason why the pain trade is never higher, is that being ‘flat’ one’s benchmark still means being outright long. There are US$47 trillion of equities in the MSCI ACWI index, and these are all owned by someone. The market rallying 10% means the world’s insurance companies, pension funds and individuals have US$4.7 trillion more wealth on paper. That’s hardly the more painful outcome.

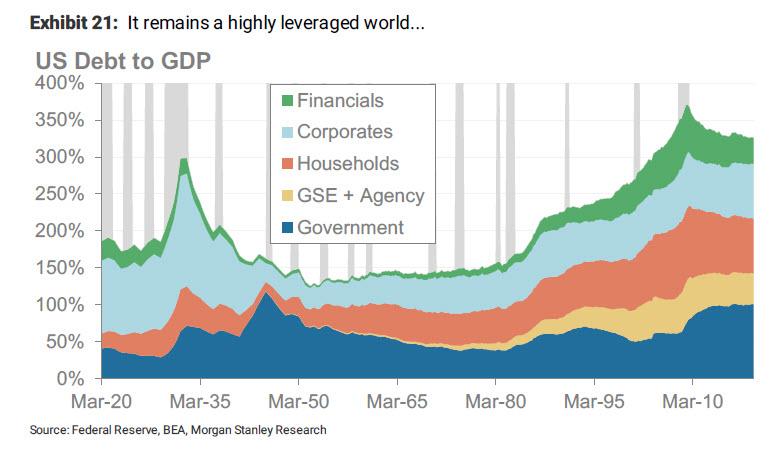

Second, and even more important, while some parts of the system have deleveraged since the GFC, the world remains a highly indebted place. In a highly leveraged world, high (and rising) asset prices help to keep this cycle going. The alternative is far more painful.

This, in turn brings us to the (widely misunderstood) “paradox of positioning.”

As Sheets concludes, “one paradox of sentiment measures is that, during times of stress (when one relies on them most), their signals can flip.” But there’s another ‘paradox’ – while cautious sentiment is frequently cited these days as a support to the market overall, how investors express this view, in sector and style, remains unusually crowded. Or, as Morgan Stanley puts it, “Caution on stocks is seen as a reason to be bullish, but optimism on growth stocks? No problem!” That is the best summary of the often hypocritical assessment by bulls, whose market takes can be summarized as heads I win, and tails… I win (when in reality it’s all the Fed).

Tyler Durden

Mon, 10/28/2019 – 15:20

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2Po3QnQ Tyler Durden