Will The Bursting Of The Tech Bubble Crash The US Office Market

If there is one thing the WeWork fiasco has taught us, it is that cracks in many legacy narratives – most notably that of “growth at any cost” over “profits and margins” – are starting to finally appear and affect investment decisions: just ask SoftBank’s Masayoshi Son who in the span of just a few months has transformed from one of Wall Street’s most admired investors to a pariah who not only does not understand simple fundamentals and instead like a clueless teenage girl chases after tall dudes with silky, long hair even if that means billions in losses, but will throw his investors under the bus just to chase a vanity investment to its bitter chapter-11 end, while sparking questions if SoftBank is the bubble era’s “Short of the Century.”

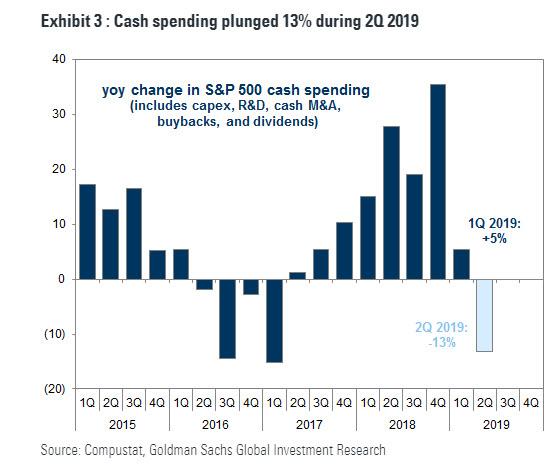

But if one digs deeper, WeWork’s house of shared office space came crashing down only after it became clear that the primary source of its heretofore unlimited growth, virtually unlimited cash spending by both companies and investors, was coming to an end, something which Goldman showed finally took place this year, as the total change in cash spending – including spending on CapEx as well as buybacks and dividends – in Q2 plunged 13% Y/Y. It’s is hardly a coincidence that that’s when WeWork’s troubles first emerged, and when its bankers scrambled to take the company public.

This is a very critical point because as Morgan Stanley’s Michael Wilson points out, at some point, the slowing business spend was likely to impact even the fast growing companies with the best secular growth stories – such as WeWork – especially if they are more dependent on corporate rather than consumer spend.

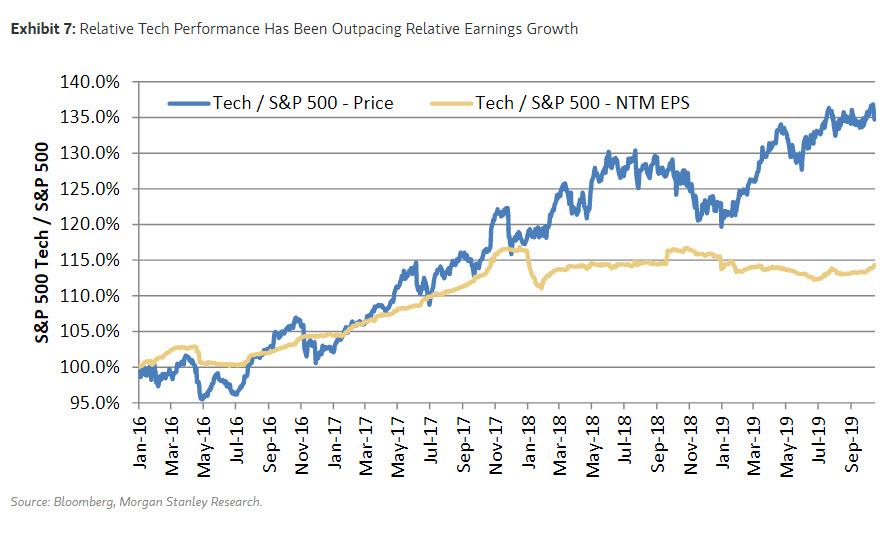

And yet, despite this sharp decline in capital spending, which has translated into flat earnings for the past two years, since July 2018 the tech sector has broadly outperformed the S&P 500 driven by multiple expansion as the forward earnings outlook of the sector relative to the market has barely budged.

Thankfully, Morgan Stanley has shown this unprecedented divergence in the following chart which makes it all too clear that the second tech bubble started some time in the summer of 2017 and since this summer it had never been bigger, as can be seen in the following chart from Morgan Stanley showing the second tech bubble in all its multiple expanding glory.

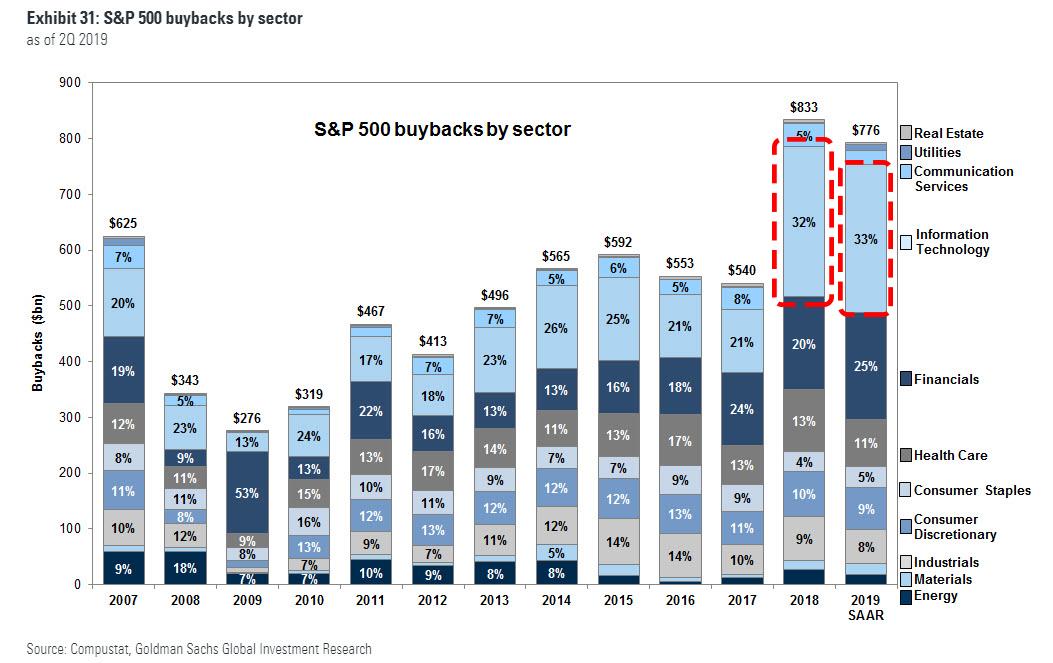

Incidentally, for those wondering just what made this historic divergence possible, look no further than the companies themselves: in the past two years, thanks to Trump’s tax repatriation holiday, tech companies unleashed a historic stock buyback spree that makes everything else pale by comparison. It is this furious stock repurchasing by tech companies that allowed their stock prices to diverge so massively from their underlying fundamentals.

How does it all end? While it is taking the market a long time to realize what was obvious to Wilson over a year ago, slowly but surely, the unpleasant truth is starting to emerge, and as Morgan Stanley’s Wilson concludes, “with a slowing economy and mounting evidence that even Software companies are not immune to this slowing, and continued demand weakness in the more capital intensive parts of Tech, we remain underweight.”

Said otherwise, as we concluded last week, “the second tech bubble is now over.” What are the implications?

If indeed “time’s up” for growth names in general (as Morgan Stanley argued again earlier today), and tech in particular, one of the most direct consequences could be a major blow to the US office market, and not just via the fiasco that is WeWork, which just happens to be the single biggest tenant in New York City, as well as Chicago, Denver and central London (as explained in “Here Are The Billions Of Loans Exposed To A Potential WeWork Bankruptcy“.

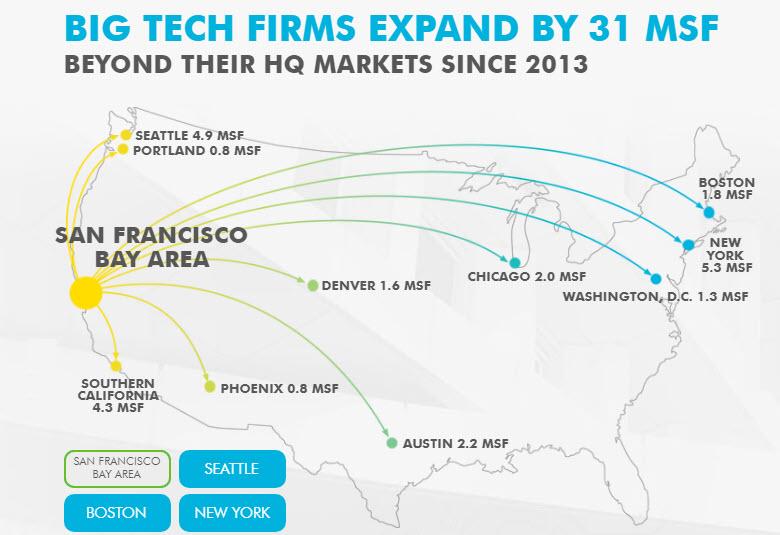

According to ReCode, citing new data from real estate firm CBRE, tech companies accounted for a record 21% of major office-leasing activity in the US and Canada in the first half of 2019. That’s double from just 11% when the firm first began collecting this data in 2011. (incidentally, CBRE doesn’t consider WeWork office space to be in the tech sector.)

As ReCode notes, “Tech’s growing stake in real estate reflects its growing importance to the overall economy. In turn, the success of the tech sector increasingly determines the success of other industries, like real estate, that rely on it.”

Over time, Tech’s dominance has only increased, and the sector has claimed the largest share of office-leasing activity since 2014 when it outpaced the business services sector, which includes industries like consulting and accounting. While CBRE doesn’t have data going back to the dot-com era, its Director of Research and Analysis Colin Yasukochi said the rate of new leases was likely even lower than it was in 2011, since many of those companies were concentrated in the Bay Area. In contrast, ReCode notes that the current iteration of tech companies is leasing real estate in cities across North America.

Similar to the stock market, where the fate of the S&P500 is increasingly in the hands of just a few companies, nearly one-third of new tech office-leasing activity is coming from just 10 firms, which include the FAANGs (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, and Google), of which four are currently facing government anti-trust scrutiny, in part because of their enormous size.

All this leasing growth stems from increased employment in tech, which has outpaced all other sectors in job growth following the recession, according to CBRE. “The labor market is driving this trend,” Yasukochi told Recode. “The tech industry is the largest source of demand for office space in the country at this time.”

Generally, these employers are locating their offices where they can find much-needed tech talent, often in areas with tech universities or other tech companies. But it’s not limited to these cities: Some tech workers are less tied to specific places, thanks to the advent of remote work.

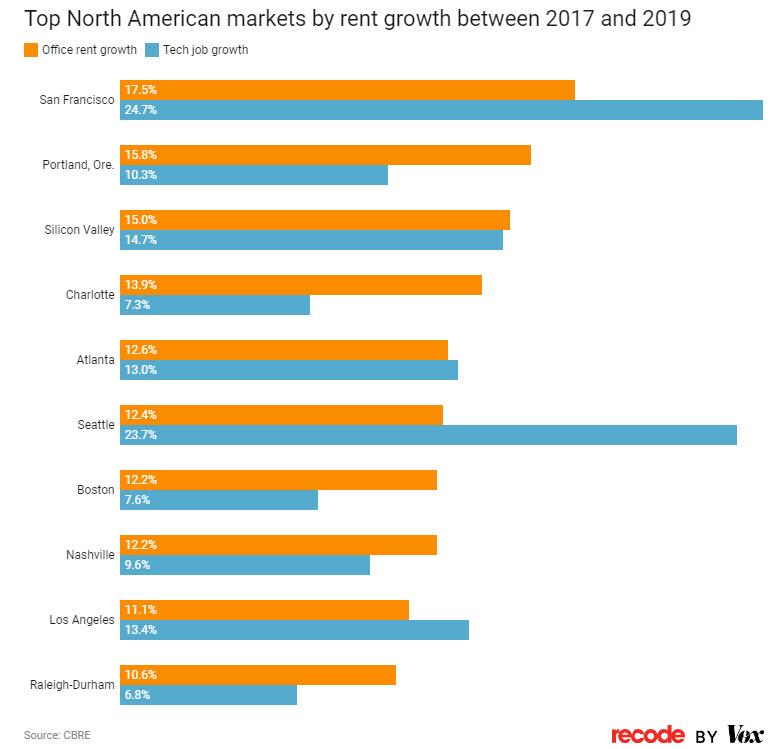

Of course, as demands has surged, so have prices, and while overall the success of tech companies has been good for the labor market, the surge in rents has been painful for smaller companies. Ten markets, including the San Francisco Bay Area, Atlanta, and Portland, Oregon, posted double-digit rent hikes in the last two years.

Other side effects of the tech bubble’s frenzied growth in recent years has been the jump in housing prices in key tech hubs as well as generally higher costs of living.

This all raises the question of what will happen i) in the case of an eventual recession and ii) once the tech bubble, that has been the primary drive of the US office market in the past decade, bursts .

Yasukochi’s answer leaves much to be desired; the CBRE director said that tech’s diversity, in that so many aspects of our lives now rely upon tech, will help insulate the sector from a recession and from causing major real estate upheaval.

“We don’t really see any severe downside scenario. We see something more similar to something like the 2008 recession where tech will slow — it’s not immune — and slow the growth of employment,” he said. “Because the industry is being led by the largest and most profitable tech companies out there, they have the wherewithal and stamina to weather any kind of economic slowdown or downturn.”

If that answer sounds very familiar, it’s because it is. When asked in July 2005 if there is a housing bubble, what is the worst-case scenario if we were to see prices come down substantially across the country, Ben Bernanke responded simply:

I guess I don’t buy your premise. It’s a pretty unlikely possibility. We’ve never had a decline in house prices on a nationwide basis. So what I think is more likely is that house prices will slow, maybe stabilize: might slow consumption spending a bit. I don’t think it’s going to drive the economy too far from its full employment path, though.

That’s precisely what the CBRE’s head researcher said now.

As for Bernanke, not only was he catastrophically wrong, but his mistake could not have been greater: just over two years later, the US economy suffered the biggest financial crisis as a result of the housing bubble – which was created only thanks to the Fed’s easy monetary policy in the aftermath of the dot com bubble – bursting, and not a single central banker was ready for that “unlikely possibility.”

Tyler Durden

Sun, 10/27/2019 – 20:50

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2PqUnwa Tyler Durden