Deepfakes Paranoia Considered Pointless

Authored by Byrne Hobart via Medium.com,

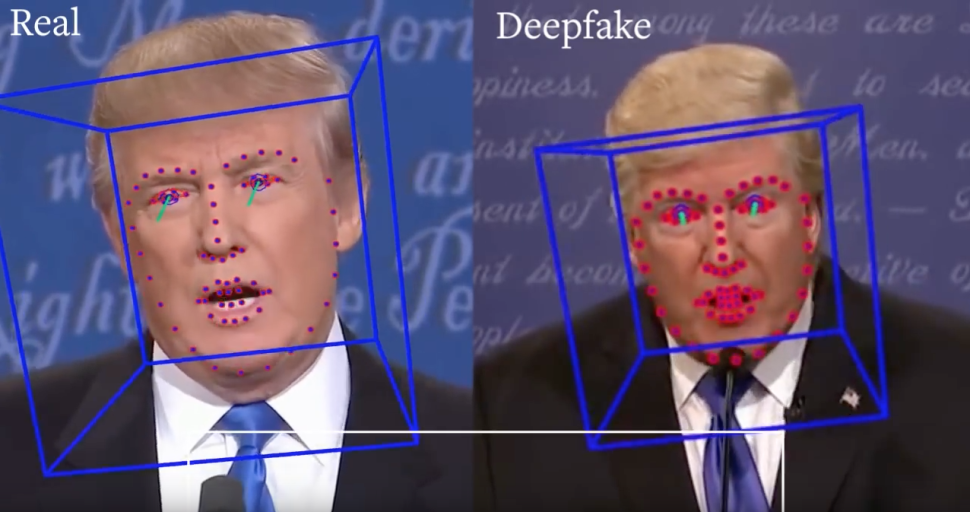

Deepfakes paranoia is the dumbest worry in the world…

The concern is that AI has gotten so good that we’ll be able to create videos of important people saying all sorts of nutty things, which will lead to a total breakdown in our ability to trust important institutions.

The problem here is that world leaders already say incredibly nutty things. Making a fake video of Donald Trump saying something outrageous is superfluous, like photoshopping a picture of Jeff Bezos so he’s holding a twenty dollar bill.

The other problem is that the media suffer from an intellectual autoimmune disorder, and relentlessly hype up minor misstatements into full-blown hysteria. If you’re at all partisan, you can think of examples of The Other Guys doing this. Every educated person knows that “cling to guns and religion” was a sympathetic remark from a churchgoer, except of course for the educated people who know that Mitt Romney’s “47%” line was a rhetorical flourish about people who pay no Federal income taxes.

The point is not to take sides; anyone who wants to win 270 or more electoral votes is going to say some dumb things, simply because low-information voters are the easiest to persuade and the easiest to lie to. If your options are either a) to patiently explain how your technocratic policy ideas artfully thread the needle between disparate goals for a variety of constituencies, or b) to rant about how the other party hates your country, your family, and your wallet, option B wins every time.

Seizing the Memes of Production

Internet discourse has gone through discrete ages. As Slate Star Codex recently noted, there was a time when debates about atheism were the single most important topic on any message board, and threatened to swallow all other forms of discourse. Before that, though, the Default Debate that ate everything else was on the ethics of music piracy. (You know it was a long time ago because nobody had enough bandwidth to download entire videos.)

This topic was huge, sprawling, and it came up all the time. One of the common rhetorical flourishes was to bite the bullet: a popular PSA compared downloading pirated content to stealing a car, and pirates would note that, if “stealing” meant costlessly duplicating a car, they absolutely would. The crux of the issue was this: is stealing about depriving the owner of their property, or depriving the seller of their power?

Eventually, we more or less resolved the piracy debate through a simple expedient: Spotify — with the help of a Napster cofounder — built a UI that was, finally, easier than piracy. As it turned out, the problem music pirates were solving was not that it music was too expensive, it was that the purchase experience was awful.

Today, the deepfakes debate is remarkably similar. The issue is not so much that anyone can make a deceptive video; it’s that the media are losing their monopoly on deceptive editing. It used to be that if you wanted a video of a politician saying something boneheaded, you had to painstakingly assemble hours of video, then maliciously stitch together whatever narrative they need. Getting internet access at a young age is a good way to develop immunity; ideally you’d think of any non-live interview as being part of the same genre as this video.

There’s a continuum between totally misleading edits and mere soundbites that sound less damning in full context. But there’s relentless pressure towards dishonest news: a neutral media source is less exciting than a partisan one, and any political news story in the US will tend to have two contradictory partisan narratives and one neutral one that makes both sides look bad. If you’re a news producer and you go with the neutral version, you’ll sound biased to anyone who heard either party’s talking points beforehand, so neutrality is, paradoxically, the most adversarial position to take.

It might seem like distorting the contents of a speech is dishonest, but to anyone sufficiently partisan, it’s not: what sounds to one observer like an out-of-context quote will sound to someone else like a revealing Freudian slip. And, of course, very few people have the interest or attention span to delve into the details.

You can view this as a crisis, or you can view it as a description of how the system works. I choose the latter: the media represent a de facto electoral college. You choose who to listen to, and they’ll give you a worldview in which voting a certain way makes all the sense in the world. In that model, deepfakes represent a constitutional crisis without the constitution: we had a setup where a small number of people could manufacture pleasant lies, but now everyone has access to an informational ghost gun printer. Scary, sure, but mostly to the people who were safely in charge in the old status quo.

The Truth Matters, But Not To Voters

In a recent profile of Amy Klobuchar, The Economist says “She can see Iowa from her front porch in Minneapolis, she says in Sigourney, a flyspeck of coffee and antique shops amid vast acres of corn country. She can see Canada from it, too, she adds, in a quick pop at Sarah Palin…” This is, of course, a reference to Palin’s infamous claim that one of her foreign policy credentials was that she could see Russia from her house. But… that was Tina Fey.

Two people famous for playing politicians on TV

Does it really matter if, uncharitably, journalists can’t tell the difference between C-SPAN and SNL, or, charitably, if they think their readers can’t? Not especially. An elected official is a consumer packaged good, not a person; they’re devised by marketing teams and sold through complex omnichannel campaigns, which have more to do with mood affiliation than policy. A slight shift in the relative importance of formal PR and guerilla marketing doesn’t make a huge difference in the ultimate outcome, it just affects whether or not mainstream journalists can hold on to their prestige.

One early narrative about the Internet was that it meant anyone, anywhere, could be their own New York Times or Wall Street Journal. Now, journalists are in a tizzy because the Internet means anyone can be their own Sergei Eisenstein or Leni Reifenstahl. As it turns out, these are the same thing.

Tyler Durden

Sat, 11/02/2019 – 17:30

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/33amSCv Tyler Durden