China Launches Stealth Rate Cut By Switching Benchmark Lending Rate, Lowering Funding Costs

More than 4 years since the last official Chinese rate cut (not of its far more targeted Required Reserve Ratio but its broad Benchmark rate), economists and pundits were wondering when, if ever, Beijing would finally cut its main rate again to ease financial conditions again at the broadest level and boost fading corporate profits while kickstarting the country’s moribund economy whose GDP is now growing below 6% GDP, the lowest on record. To be sure, China has had its share of setbacks in the past year preventing it from implementing the type of monetary policy it desires, most notably soaring food inflation as a result 110% pork CPI…

… even as producer prices, a driver of industrial profits, slumped below zero earlier in 2019, a clear indicator that China’s enterprises desperate for lower rates.

And yet, a wholesale easing, such as cutting the benchmark rate, could potentially spark even more food inflation, setting off violent popular protests. After all, the Chinese population’s patience is already running thin, forcing Beijing to scrap import tariffs on US pork exports, a move which Xi Jinping (and Trump) quickly spun as a trade war concession, but in reality was a matter of preserving the peace for China which is desperate for any sources of cheaper protein to keep its 1.4 billion people fed, and happy.

Well, overnight China finally did what so many had been expecting to do, if once again it did so in a roundabout way.

Remember that back on August 17, China’s central bank unveiled detailed measures on its long-awaited interest rate reform by establishing a reference rate for new loans issued by banks to help steer corporate borrowing costs lower and support a slowing economy.

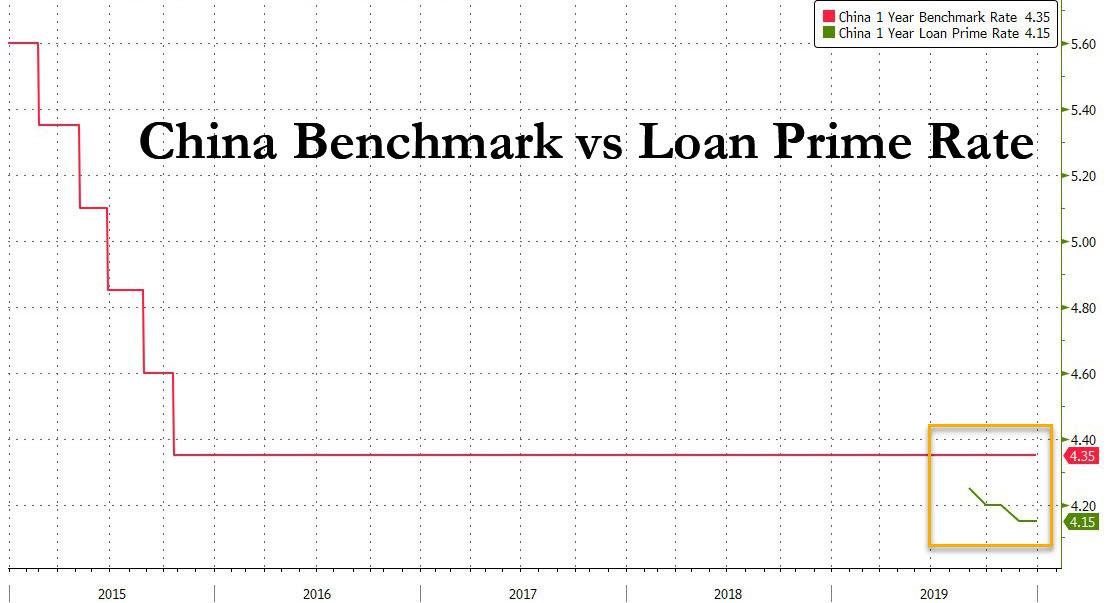

As a key part of the rate overhaul, the Loan Prime Rate (LPR) would eventually become the new Benchmark Reference Rate to be used by banks for lending which is aimed at supporting funding as well as lower borrowing costs for small businesses; the rate will be set monthly (20th of every month) and will be linked to the Medium-term Lending Facility rate. The current 1 year LPR stands at 4.15% after its latest cut on Nov 30 versus the Benchmark Rate 4.35%.

So even with the PBOC pushing the LPR lower by 10bps since its August inception, the benchmark rate has remained unchanged at 4.35% since October 2015.

It is in this context that on Saturday, China’s entire interest rate framework was overhauled when the PBOC ordered lenders to adopt the new LPR rate as the de facto basis for all credit from next year, marking an end to the previous benchmark in what Bloomberg said was another step toward liberalizing the financial system (although many disagree).

In a statement, the PBOC said that financial institutions should stop using the old lending rate as the pricing reference for all credit from January, and gradually convert existing loans to a new base using the loan prime rate, from March to August. The one-year lending rate had provided the previous anchor for loans across the economy.

And since the PBOC is effectively forcing lenders to adopt a reference rate that is 20bps lower than the benchmark, Saturday’s announcement is effectively stealth easing, and will lower costs for the roughly 152 trillion yuan ($21.7 trillion) in yuan-denominated outstanding loans held by financial institutions and boost economic growth, even though – as with most things in China – it does not involve a straightforward cut to interest rates.

The transition is “in line with the need to further reduce the financing costs for the real economy, although there’s still a long way to go,” said Fan Ruoying, analyst at the Bank of China’s Institute of International Finance in Beijing, as quoted by Bloomberg. The shift to the LPR comes at a time when Beijing has unveiled a raft of pro-growth measures, including tax cuts, more infrastructure spending, reductions in the amount of cash banks must keep on reserve and lending rates to boost credit.

Ironically, while the move will benefit end-consumers and debtors, it could have an especially adverse impact for creditors, forcing even more bank failures, bank runs, bailouts and nationalizations. As Fan warned, “the move will present more challenges for commercial banks because the interest margin will be squeezed and lenders will need to improve their pricing ability.” As a reminder, many of the small and medium-bank failures that took place in 2019 – and there have been more this year than ever on record – have been attributed to the ongoing drop in rates that banks can charge client which in a time of shadow bank crackdowns, has meant more bank failures amid a flattening of the Net Interest Margin curve.

“The purpose of the step is to make interest rates more market-driven and help lower financing costs,” said Wen Bin, an economist at Minsheng Bank in Beijing.

To be sure, the impact of the loan reform won’t be groundbreaking as most new loans issued in the past 4 or so months already track the LPR: “By now close to 90% of new loans are priced with the LPR, but outstanding loans with floating rates are still based on the benchmark lending rate,” the central bank said in a separate statement. That means the real lending cost “can’t reflect changes in market interest rates.”

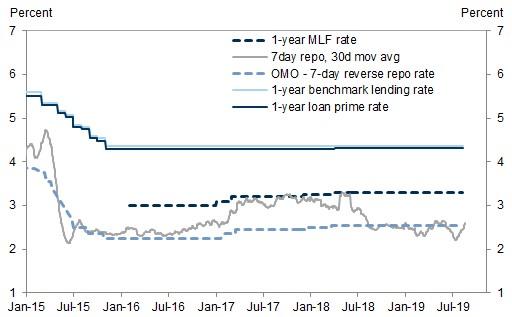

Why did the PBOC decide to shift to the LPR, which we also dubbed China’s Libor rate when we discussed it in the summer, besides providing it a convenient way to cut rates by 20bps without actually implementing a 20bps rate cut? As a reminder, the rate which will become the benchmark for new loans this year, is based on the interest rate for one-year loans that 18 banks offer their best customers. Banks submit the quoted price each month in the form of a spread over the rate of the PBOC’s medium-term loans.

According to Bloomberg, the move may help make monetary policy more effective, resolving a long-standing problem in which cheap funding that the PBOC offers banks doesn’t result in cheaper loans to businesses. In the new scenario when all borrowing is based on the LPR, the supply of central bank funding or cuts to the rates of medium-term loans will in theory push down the LPR, and reduce the cost of all lending to businesses. One can almost call it trickle down credit with Chinese characteristics…

Whether or not such a move will succeed remains to be seen, but one thing is certain: the transition to just one short-term rate will simply somewhat China’s arcane rate system. The following Bloomberg explainer makes it clear why this was long overdue: most central banks govern the price of money in an economy via the rate that banks are charged to borrow cash over short time periods. In China, that approach had been divided into two steps. First, the PBOC guided prices for funding in the inter-bank market via its reverse repurchase agreements and medium-term lending facility. Then, it set the benchmark rates that were used to price mortgages, business loans and other commercial lending – the one-year and five-year lending rates.

So will a successful transition from a benchmark to an LPR rate stoke another asset bubble? Perhaps, although the PBOC is careful to avoid overheating among China’s most important assets: housing. While the interest rate of home mortgages should also be converted to the LPR, the central bank said that the new borrowing cost must be the same as the current charges to “reflect the request to regulate the property market.” Eventually, at some point in the future, home mortgages could be repriced in the future, based on the LPR, the PBOC said, giving itself a buffer for when China’s housing market takes its next leg down.

And while Bloomberg concludes that this latest stealth rate cut shows the PBOC’s “commitment to making the interest-rate system more market-driven” controls on deposits remain for now. In short, the step-by-step approach appears to be trying to open up the system without shrinking interest margins too rapidly and adding more pressure to smaller lenders. Unfortunately, with numerous banks having already failed previously in 2019 (as discussed here), and with more than half of China’s banks failing a recent central bank stress test, the only guaranteed outcome from this weekend’s effective rate cut is that, paradoxically, it will only accelerate the rate of failure of China’s already cash strapped, and in many cases insolvent, banks.

Which begs the question: did Beijing, in hopes of gently stimulating the economy, start a cascade of failures that will eventually drag down more than just the small and medium banks (and result in the executions of many more bank CEOs) despite such “brilliant” marketing ploys as offering a pound of pork to starving savers with every new deposit, and precipitate China’s long-overdue financial crisis?

Tyler Durden

Sun, 12/29/2019 – 15:00

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/37gMMWL Tyler Durden