China Cuts Reserve Ratio By 50bps Ahead Of January’s $400 Billion “Liquidity Hole”

Just three days after China quietly cut rates by 20bps when it ordered banks to switch from the traditional Benchmark 1 year rate to the new Loan Prime Rate (aka China’s LIBOR) as the reference rate for new short-term loans, effectively lowering the prevailing rate from 4.35% to 4.15% (in the process further pressuring bank net interest margins), on the first day of the new 2020, the PBOC unveiled widely expected another boost for the slowing Chinese economy: the central bank announced that starting Jan 6, it will lower the required reserve ratio (RRR) – or the amount of money banks are required to have on hand – by 50bps for commercial lenders, in the process releasing about 800 billion yuan ($115 billion) in liquidity from the cash-strapped financial system.

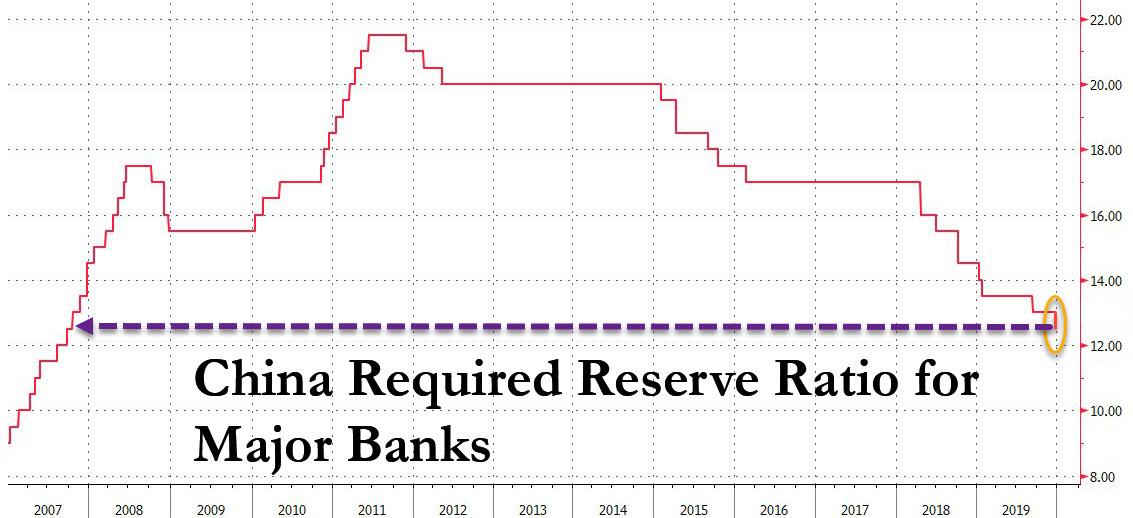

Currently the required reserve ratio is 13% for large banks and 11% for small banks. The cut, which is the first since September, will bring the blended reserve ratio for Chinese banks to the lowest level since October 2007.

The 50bps RRR cut is meant to help banks reduce their lending rate to businesses, the PBOC said in a separate statement, which is ironic because while on one hand the PBOC pressures commercial banks by ordering them to lower the amount of interest they can charge customers by 20bps (with the benchmark rate recalibration), on the other it boosts systemic liquidity to offset the adverse effects of its first action, something we predicted would happen earlier this week, to wit:

… with more than half of China’s banks failing a recent central bank stress test, the only guaranteed outcome from this weekend’s effective rate cut is that, paradoxically, it will only accelerate the rate of failure of China’s already cash strapped, and in many cases insolvent, banks. As such we expect that the PBOC will promptly follow through with another RRR cut to offset the adverse side-effects of this particular rate cut, by injecting more liquidity in the banking system.

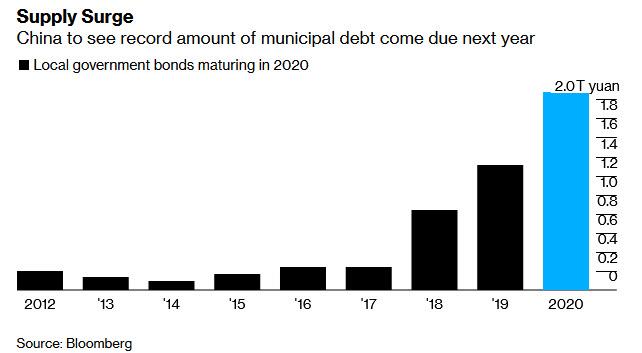

Of course, it wasn’t just us predicting an imminent RRR reduction: the cut was first signaled by Chinese premier Li Keqiang in December 2019. It’s also in line with market expectations that the PBOC will increase funding to the financial system in January to ease a liquidity crunch caused by rising local government debt sales and increasing cash demand during the Spring Festival holidays.

As a reminder, two weeks ago we warned that China is facing a potentially destabilizing “liquidity hole” of 2.8 trillion yuan ($400 billion) in January as people across the nation will withdraw cash for the Lunar New Year holiday, which this year falls on Jan 25. China’s most important annual holiday is a time when companies and individuals typically need large amounts of cash on hand to pay bonuses, clear debts and cover other expenses. In addition to seasonal cash needs, China’s bond market also faces a major maturity deluge, as more than 2 trillion yuan in notes mature in early 2020, and fresh debt to refinance the borrowing thus shoring up economic growth will probably start hitting the market soon.

Sure enough, in addition to offsetting the reduced net interest margin, the PBOC said that the injection will be offset as banks provide more cash to the public before the Spring Festival, and the overall liquidity level at banks will be kept stable. “Prudent monetary policy stance remains unchanged,” it added.

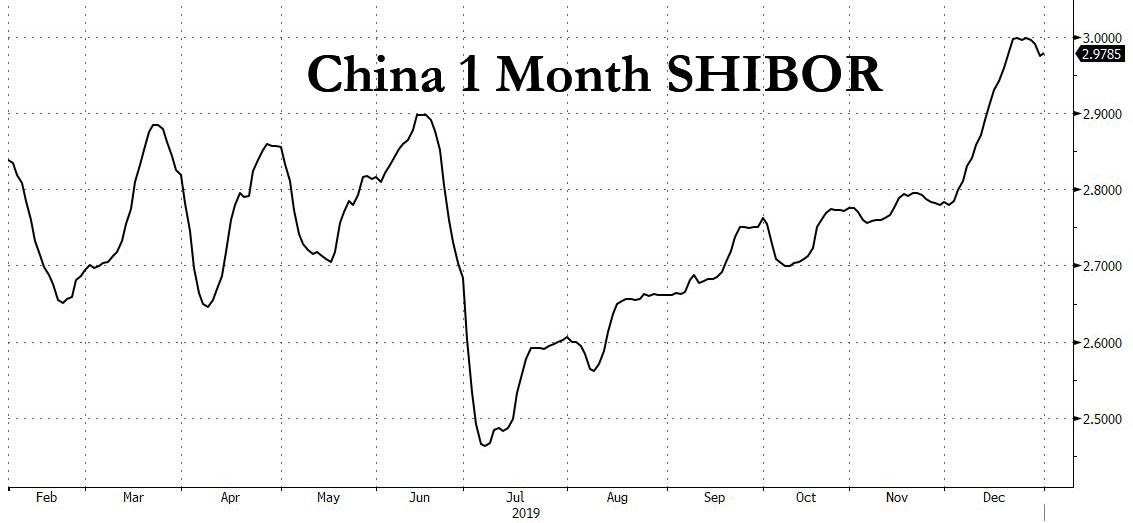

It was fears about an impending liquidity shortfall that sent China’s 1Month SHIBOR to the highest level in one year, briefly touching 3% a few days ago.

However, now that China is engaged in a delicate balancing act, on one hand reducing the amount of cash banks can earn by lending money to customers, and on the other releasing systemic liquidity, the question is whether the PBOC’s latest efforts to stimulate the economy will destabilize the banking sector further.

Addressing just this, the PBOC said the planned reduction will save about 15 billion yuan in funding costs for banks in a year, indicating that the benchmark loan prime rate will likely be lowered as banks reduce their submissions for the rate’s calculation in late January, which in turn will force the PBOC to cut the RRR further, resulting in an even lower loan prime rates and so forth, which brings to mind a recent striking op-ed published in the Global Times, which predicted that China would be the next major country to cut rates to zero.

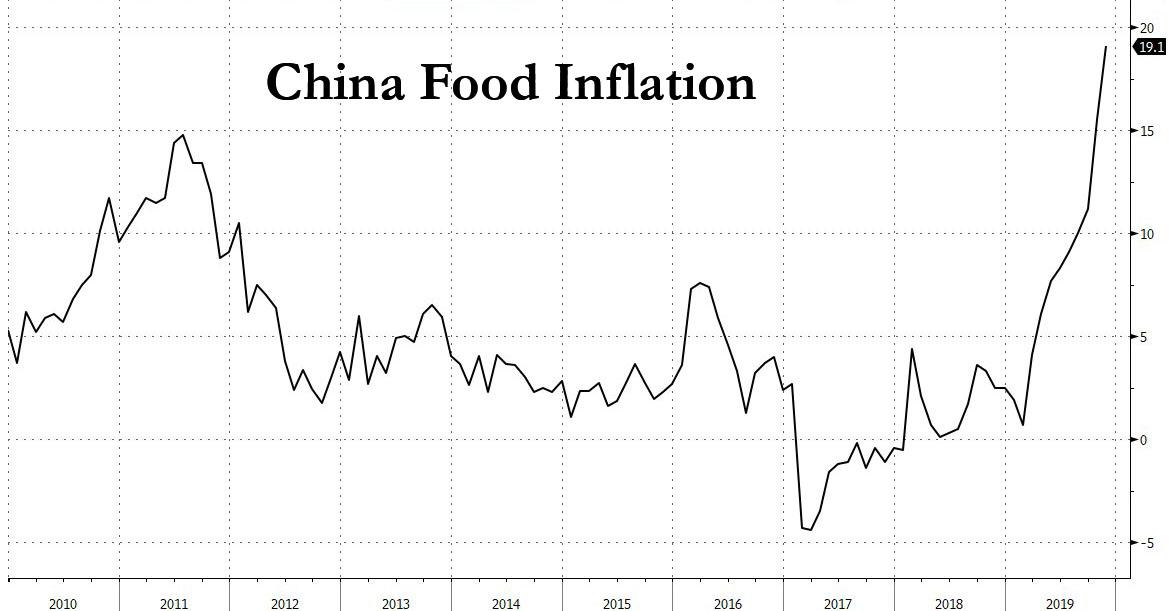

And while Xinhua quoted an unidentified central bank official as saying that Wednesday’s move does not presage a large-scale government stimulus program, noting that “the stance of prudent monetary policy has not changed” and ruling out the possibility of a “flood-like” flow of fresh money, Beijing may have no choice, even if food inflation is now far higher than 2011, when the RRR was just shy of 22%.

“Looking ahead, there’s still room for more reserve ratio cuts in 2020” to mitigate the impact of deleveraging at small banks, wrote CICC economist Eva Yi. “Should economic growth show more signs of stabilization and recovery after the cut, it’s likely the central bank will slow down the pace of further reserve ratio cuts.” Then again, since China’s economic slowdown had little to do with the trade war and everything to do with its massive debt load, accelerating bank failures, record debt defaults and record bad debts, we have a feeling that if there is a change to the pace of RRR cuts it will be the opposite of “slowing.”

Tyler Durden

Wed, 01/01/2020 – 10:01

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2tofgzi Tyler Durden