Digital Currency: What Do The Global Banking Elite Want?

Amidst the annual spectacle of the World Economic Forum in Davos, the Bank for International Settlements this week announced that multiple central banks have created a group that will ‘assess potential cases for central bank digital currencies‘.

Here is the press release from the BIS in full:

The Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank, the Sveriges Riksbank and the Swiss National Bank, together with the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), have created a group to share experiences as they assess the potential cases for central bank digital currency (CBDC) in their home jurisdictions.

The group will assess CBDC use cases; economic, functional and technical design choices, including cross-border interoperability; and the sharing of knowledge on emerging technologies. It will closely coordinate with the relevant institutions and forums – in particular, the Financial Stability Board and the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI).

The group will be co-chaired by Benoît Cœuré, Head of the BIS Innovation Hub, and Jon Cunliffe, Deputy Governor of the Bank of England and Chair of the CPMI. It will include senior representatives of the participating institutions.

As with every other recent development in regards to CBDC’s, the BIS stand at the heart of the issue. The new central bank grouping comes just over six months after the BIS first established an Innovation Hub for central banks (also known as Innovation BIS 2025) with the objective being to ‘foster international collaboration on innovative financial technology within the central banking community‘.

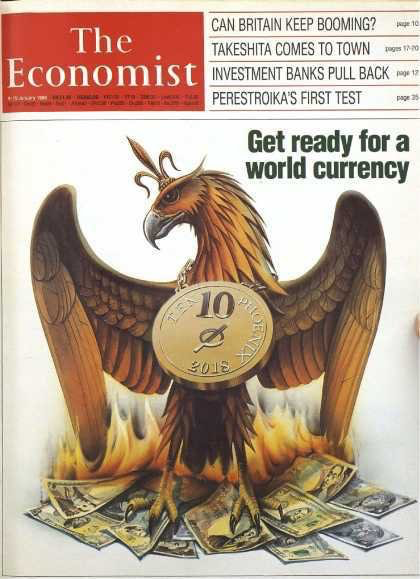

With the agenda to introduce central bank digital currency gathering further momentum, now would be as good a time as any to ask what the global banking elite are seeking to achieve over the short to medium term.

In 2019 I published around a dozen articles on the subject of digital currency, examining the latest speeches from central bankers and the actions they were taking to formulate the foundations for a cashless society. The Innovation BIS 2025 project is a important pillar to the aspirations of the financial elite. By 2025 they are targeting the completion of reformed payment systems in the UK, the U.S and beyond, systems that will possess the capability to interface directly with Fintech firms that specialise in blockchain and distributed ledger technology (DLT). Both blockchain and DLT would be essential for the roll out of a fully fledged CBDC network.

During a speech at the Central Bank of Ireland in March 2019, BIS General Manager Agustin Carstens stated plainly what a CBDC future would look like:

Like cash, a CBDC could and would be available 24/7, 365 days a year. At first glance, not much changes for someone, say, stopping off at the supermarket on the way home from work. He or she would no longer have the option of paying cash. All purchases would be electronic.

To avoid confusion, there are two variants of CBDC that are regularly discussed by central bank officials. The first is a wholesale CBDC, which would be used to facilitate payments exclusively between financial sector firms. The second option, a retail CBDC, would be for use by the general public.

To quote Carstens from the same speech he made in Ireland:

A CBDC would allow ordinary people and businesses to make payments electronically using money issued by the central bank. Or they could deposit money directly in the central bank, and use debit cards issued by the central bank itself.

This would be a significant departure from the traditional model of commercial banks digitising the money held in people’s bank accounts. To way up the likelihood of this scenario, let’s examine what the International Monetary Fund have been saying.

Former Managing Director Christine Lagarde, who is now President of the European Central Bank, addressed the Singapore Fintech Festival in November 2018 and hinted at how the future composition of a CBDC could look:

If digital currencies are sufficiently similar to commercial bank deposits— then why hold a bank account at all?

What if, instead, central banks entered a partnership with the private sector—banks and other financial institutions—and said: you interface with the customer, you store their wealth, you offer interest, advice, loans. But when it comes time to transact, we take over.

Banks and other financial firms, including startups, could manage the digital currency. Much like banks which currently distribute cash.

In this reality, central banks would, according to Lagarde, ‘retain a sure footing in payments‘. By extension, they would also retain autonomy over an all digital financial system.

The IMF expanded on Lagarde’s speech in December 2019 with the publication of an article called, ‘Central Bank Digital Currencies: 4 Questions and Answers‘. Co-written by Tobias Adrian, the Financial Counsellor and Director of the IMF’s Monetary and Capital Markets Department, it asserts that the IMF is now gradually helping countries ‘develop policies‘ as they ‘consider CBDC options and seek advice.’

One of those options is a public-private partnership, which IMF staffed have termed as a ‘synthetic CBDC‘. In the summer of 2019 Mark Carney first raised the prospect of a ‘Synthetic Hegemonic Currency‘ that could be provided by the public sector ‘through a network of central bank digital currencies‘. This would ultimately be at the expense of the world reserve status of the dollar.

The synthetic CBDC model as envisioned by the IMF would see private sector firms like JP Morgan and Barclays issuing digital coins to the general population. Banks would continue ‘innovating and interfacing with customers‘, whilst central banks would ‘provide trust to the system by requiring that coins be fully backed with central bank reserves and by supervising the coin issuers.’ This is worth keeping in mind because as the article confirms, such a set up would ‘preserve the comparative advantages of each participant.’ In other words, global financial institutions and the central banks operating beneath them would work hand in hand with Fintech developers rather than be in competition, creating a state / private lock in that every citizen would be bound by due to the abolition of cash.

The coins the IMF refer to are known as ‘Stablecoins‘, which central bankers routinely discussed throughout 2019. Stablecoins are regarded as a form of crypocurrency, and differ from the likes of Bitcoin in that issuers of the coins would back them using a basket of established fiat currencies. The theory is that this would give the coins stability in terms of their valuation. Stablecoins would be all digital with blockchain and distributed ledger technology central to their make up, meaning payments would be instantaneous across borders.

A few days after the IMF’s article, Lael Brainard of the Federal Reserve addressed an event held in Frankfurt, Germany in honour of Benoit Coeure’s departure from the European Central Bank (the same Benoit Coeure who has now begun his new role heading up the Innovation Hub at the BIS).

This was an important speech because between the lines Brainard set the scene for how central banks could take advantage of the rise in stablecoins. She talked of how the emergence of crypto technology has raised ‘important questions for central banks‘, and that the ‘prospect of global stablecoin payment systems has intensified the interest in central bank digital currencies.’

Facebook’s Libra project is cited by central banks as the bellwether of stablecoins. Whilst Libra has yet to launch, implementation would give it the title of a global stablecoin used throughout multiple different jurisdictions. For Brainard and her colleagues, this brings into question the level of regulation and safeguards that they deem necessary for stablecoins to be rolled out world wide. Without them, Brainard warned, ‘stablecoin networks at global scale may put consumers at risk‘ as well as the financial system as a whole.

There are also questions related to the implications of a widely used stablecoin for financial stability. If not managed effectively, liquidity, credit, market, or operational risks, alone or in combination, could trigger a loss of confidence and run-like behaviour.

Chief amongst the risks raised are money laundering and the financing of terrorism, and it is here where the distinction between a permissioned and permissionless stablecoin network becomes apparent. Central bankers openly advocate for a permissioned network where access must be granted by participants. A permissionless network, according to Brainard, ‘may be more vulnerable to money laundering and terrorist financing.’

One solution mooted by Brainard would be for coordinated regulatory action rather than individual nations determining how stablecoins would be allowed to function. In Brainard’s words, ‘any global payments network should be expected to meet a high threshold of legal and regulatory safeguards before launching operations.’

Elites have been fashioning for decades the narrative that global problems are too large and complex in scale to be remedied at the national level. Their argument has been that more centralisation of powers and the diminishment of the nation state is required to bring about order out of chaos. The seeming regulatory vacuum surrounding stablecoins has given central banks the platform to gradually begin cementing central bank digital currency as a safer alternative, primarily because they would be a ‘direct liability of the central bank.’

As the debate continues around digital currency, the Federal Reserve are quietly progressing with plans to introduce a new payments system called ‘FedNow‘. This will be a platform where users would be able to ‘send and receive payments immediately and securely 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.’

The biggest selling point of digital currency is the convenience factor of national and cross border payments being settled and available without delay. I suspect this is where the banking elite want people to focus their attention, as opposed to how a digital currency network that incorporates central banks and selected private sector players would result in the end of tangible assets.

If you believe what central bankers are saying, then the concept of CBDC’s remain at the investigative stage. Sweden continues to lead the way with the development of an e-krona. The Riksbank has now procured a technology supplier to begin an e-krona test pilot, with the leading objective being to ‘broaden the bank’s understanding of the technological possibilities for the e-krona.’

With the Riksbank being part of the new central bank group working through the BIS, and the IMF admitting that they are now assisting countries in devising policies around digital currency, we are witnessing just how closely they are all collaborating with one another.

One question is whether stablecoins will be used as a stalking horse for CBDC’s, taking them beyond a mere concept. Financial instability has always been an opportunity for the global elite. Stablecoins without sufficient regulatory oversight create an opening for central banks to step in further down the line.

Something to ponder also is how faith could be lost with future stablecoin providers. BIS General Manager Agustin Carstens has said before that trust can be compromised in four particular ways – currency devaluations, hyperinflation, wide-scale payment system disruptions and bank defaults. Naturally, Carstens has positioned central banks as the institutions that can rectify such conflict, even though it has been proven that throughout history it is their policies that have created economic instability leading to collapse.

In relation to what Carstens said about compromising trust, three months prior to the EU referendum Bank of England official Ben Broadbent made a very telling comment in a speech appropriately titled, ‘Central banks and digital currencies‘, about the necessity for currency degradation before the public demand a solution to the traditional monetary model.

Degrade a currency sufficiently, via hyperinflation and collapse of the banking system, and people will eventually look for alternatives. But that’s generally the sort of thing that has to happen. Almost always, these currency substitutions occur only once the existing currency has become deeply compromised. Even then, the thing people naturally reach for is an existing, trusted currency – often the US dollar – rather than some entirely new unit of account.

When currency substitution has occurred naturally it’s almost always done so only after the incumbent currency has been debauched by hyperinflation.

I have warned extensively over the past couple of years of the risk of a global trade conflict triggering higher inflation, the devaluation of currencies such as sterling and the raising of interest rates. It is what would occur afterwards that is of more concern. Would people look to central banks as the saviours in a crisis scenario, giving them licence to digitise all assets through a network of CBDC’s?

As ever, central banks will require sustained geopolitical conflict to shape the future design of the financial system. They are already headlong in devising that very system through the reformation of global payment systems. But with distractions in the shape Brexit and Donald Trump’s presidency still dominating the discourse, potentially up to 2025, how many are even aware of what the central banks are planning?

Tyler Durden

Sat, 01/25/2020 – 16:20

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2vmZ16s Tyler Durden