Gold: A Modern Investment Framework For An Ancient Asset

Authored by John Butler via MacroHive.com,

Gold no longer serves as an official money in the modern financial system, yet it is still considered an important asset due to its established diversification and store of value properties. But what framework(s) should we use to understand the role that gold should play in investment processes and policies? In Part I of this series, I present one useful framework which implies that gold is significantly ‘under-owned’ and, consequently, undervalued at present.

A Brief History of Gold’s Monetary Role

Most investors are familiar with the ancient use of gold and silver as money, and that gold still provided the monetary base for economies well into the 20th century. Indeed, less than a century ago, in the aftermath of WWI and associated large currency devaluations and hyperinflations in Europe, there were several international conferences held to try and strengthen gold’s role as a source of monetary and economic stability. 75 years ago the famous Bretton-Woods conference was held, formally re-establishing gold’s role at the centre of the international monetary system.

For investors of that time, gold held a central role in investment processes. It was the bedrock collateral of the financial system – the ‘risk-free’ asset – and the benchmark for measuring investment performance. Gold was also an instrument that the central banks of the day could use to help contain financial crises. In the event of a run on deposits or an interbank collateral squeeze, central banks could lend out their reserves (normally at penalty rates of interest) in order to buy time for the system to restructure and reorganise. For example, gold lending was one of the actions taken by JP Morgan to help contain the US Banking Panic of 1907. This provided a model for how the Federal Reserve was subsequently designed to act as a lender of last resort.

The last international conference to determine the role that gold should play in the global financial system was held in December 1971 at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, DC. Following President Nixon’s infamous ‘closing of the gold window’ in August that year, this conference was a last-ditch attempt to salvage what was left of the Bretton-Woods arrangements that were credited with having provided a stable monetary foundation for the rebuilding of Europe and Japan and the widespread prosperity following WWII.

The result of the negotiations was that the US agreed to devalue the dollar by 8% vs gold; major trading partners would revalue versus the dollar by 8-16%; and currencies would fluctuate in narrow bands of 2.25% versus the dollar thereafter. The hope was that this would rebalance global trade and capital flows, thereby removing the previous balance-of-payments pressure draining the US gold stock. This hope was in vain, however. The US continued to run growing balance-of-payments deficits and by 1973 the agreement was abandoned, currencies went into free-float versus one another, and, as it happened, into freefall versus gold for the remainder of that decade.

The Role of Gold Today

Most central banks hold a portion of their reserves in the form of physical gold. Subsequent to the global financial crisis of 2008-9, central banks have been accumulating gold at a historically elevated pace. As seen in the chart below, purchases reached a record high in 2019.

Chart 1: Central Bank Purchases of Gold Increased in 2019

Source: Metals Focus, Refinitiv GFMS, World Gold Council

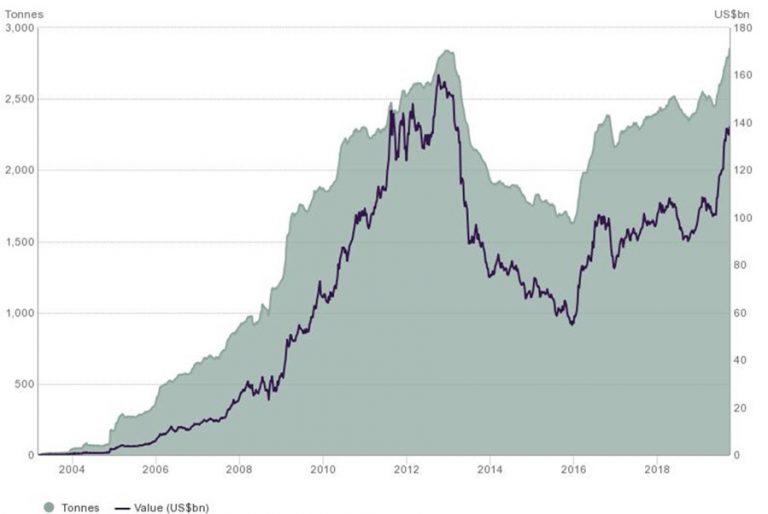

Private investors have also been accumulating gold. While Asian investors tend to acquire physical gold, those in the West commonly do so through ETFs – a proxy for overall Western investment demand, which was also particularly strong in 2019.

Chart 2: Holdings in Global Gold-backed ETFs Reached a New Record in September

Source: Bloomberg, Company Filings, ICE Benchmark Administration, Shanghai Gold Exchange, World Gold Council

A Modern Investment Framework

Although the evidence shows gold holdings increasing, my discussions with investors often centre around the lack of a robust valuation framework and gold integration into their asset-allocation processes. I provide more than one such framework, yet I always begin with an explanation not only of what gold is, but also of what it is not.

If gold is no longer official money, what exactly is it? After all, gold, an inert metal, has not changed over the past century. There remains widespread demand for gold both as jewellery and as a safe-haven asset. It is easy to understand why gold is, in fact, the safest of safe-haven assets: it carries no credit or counterparty risk, it cannot be arbitrarily devalued by governments the way their currencies can, and it requires no government to give it value with legal tender or any other official status. As such, gold can be considered both a universal, global, liquid alternative to fiat currency as a store of value. It is also an ‘anti-asset’ that, unlike all financial assets, cannot be defaulted on, restructured, repudiated, or simply rendered worthless by government action.

As such, one way in which to consider gold’s value for investors is as a form of insurance against the various risks to fiat currencies and financial assets. The concept of insurance is intuitive, and we all pay for it in one form or another. With gold, insurance is not intrinsically productive. It doesn’t provide a yield or other ex-ante return. Indeed, it ‘carries negatively’ in the form of premiums paid, just as gold normally carries negatively by not paying any interest yet incurring costs for secure storage and the insurance thereon.

The ultimate providers of insurance against risk are either governments themselves or reinsurance companies. By owning gold, investors are ‘insuring’ their financial portfolios against default and devaluation. By corollary, they are also insuring them against financial crises – a common cause of both, and one that occurs with some regularity throughout history.

How, then, are we to consider how much ‘insurance’ investors should normally hold in the form of gold? One way is to use history as a guide and to derive the ex-post optimal weighting for gold in a simple portfolio of financial assets, stocks, and bonds. Taking the longest available robust historical dataset for total returns for stocks and bonds over the past century, and solving for the gold weighting that pushes the efficient frontier out to the portfolio maximum, the answer comes out at about 15%.

Focusing on the modern financial world however (that is, the one since 1971 in which gold is no longer the basis of the international monetary system), the ideal gold weighting climbs to around 20%.

It should be stressed that these weightings are derived entirely from passive, ex-post, efficient frontier calculations using public datasets stretching back a century. Were you to take an actual ‘view’ on the future ex-ante returns, volatilities, and correlations of stocks, bonds, and gold, the derived weightings of the efficient portfolio would be different. For this exercise, we simply run the numbers as they are with no ‘view’ at all.

When I show investors the results of this analysis the initial reaction is frequently one of shock. It is the rare investor who allocates 15% of more of their portfolio to gold. But the numbers don’t lie. Indeed, they reveal some normalcy bias. When you look more closely at the data, what you see are consistently higher returns provided by a portfolio of stocks and bonds alone: the conventional wisdom. Yet there are rare periods in which stocks decline so sharply that the positive performance of bonds doesn’t compensate and, rarer still, when both stocks and bonds decline in value. So unless you were able to predict such periods in advance, you would have wanted to hold ‘insurance’ against them with a portfolio gold weighting on the order of magnitude derived above.

A Valuation Methodology for Gold’s Insurance Properties

Now let’s go one step further and consider what the implications are for the valuation of gold. Available data show that gold holdings comprise no more than 1-2% of investor portfolios. Stocks, bonds, and other assets comprise the other 98%. But unlike financial assets, which can be issued theoretically ad infinitum, the supply of gold is essentially fixed, growing at about 1% per year, much of which is absorbed into jewellery production. Therefore, the only realistic way for portfolios to shift towards the efficient frontier derived above is for the price of gold to rise versus that of financial assets generally.

Chart 3: Gold Percentage of Global Financial Assets

Source: CPM Group

If, over time, investors were to gravitate towards the historically optimal portfolio weightings derived above, holding the value of financial assets constant, gold would have to increase in value by a tenfold order of magnitude to around $15,000. Were the market capitalisation of financial assets to increase as well, say as the result of generally expansionary monetary policies, the rise in the gold price would need to be commensurately higher.

One can visualise this adjustment by assuming that the supply of gold is an essentially constant, vertical line, with demand for gold as financial portfolio insurance having some slope. As the quantity of gold ‘insurance’ demanded increases, the gold demand function shifts to the right, thereby driving the price higher.

Supply of Gold is Inelastic, While Demand Can Fluctuate

Chart 4: Supply of Gold is Inelastic, While Demand Can Fluctuate

It is spurious to try and get more precise, but this gives us an order of magnitude for the price of gold that would correspond to the historically derived, implied value of gold’s ‘insurance’ properties. Yes, this is a big figure, but it is worth keeping in mind that tenfold increases in the price of gold over multiple-year periods are hardly unprecedented. Indeed, the price of gold would rise by even more than tenfold in the 1970s, and by about fivefold in the lead-up to and aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis.

Alternatively, stocks and bonds could collectively decline in value by some 80% versus gold, presumably driven by stocks falling significantly more than bonds. But given the policy regime in effect today, that would be highly unlikely. Central banks and/or fiscal authorities would almost certainly act to prevent such a huge selloff with expansionary policies. And as observed in 2009-11 and other such periods, these policies would give upward momentum to the price of gold. I consider $15,000 gold and flat stocks+bonds to be a more realistic scenario than $1,500 gold and the SPX back under 2,000. Most realistic of all could be that bonds remain stable, stocks continue to at least keep pace with inflation, and gold outperforms over time.

As this gold framework is based on the concept of gold as the ultimate form of financial portfolio insurance, the factors impacting investor confidence are critical. As investors become increasingly concerned about the stability of the financial system, as they did during the mid-2000s, they will demand more ‘insurance’, driving the price of gold higher. As they become more complacent, the opposite should be the case.

While hindsight is always 20/20, we can see this pattern clearly in the historical data. Looking forward, investors need to consider what specific factors are likely to impact investor confidence in the future. However, from the current starting point, an ‘insurance’-based valuation framework for gold would be strongly biased towards a relative outperformance of gold.

In Part II of this series I will present a fundamental fair-value approach to modelling the price of gold, with reference to specific economic variables. As a more practical trading tool this will complement the generic ‘insurance’ framework presented here.

Tyler Durden

Mon, 02/10/2020 – 20:45

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/37gwble Tyler Durden