From The Woke Elite To Walmart: The Surge Of ‘Preferred Pronouns’

Authored by Richard Bernstein via RealClearInvestigations

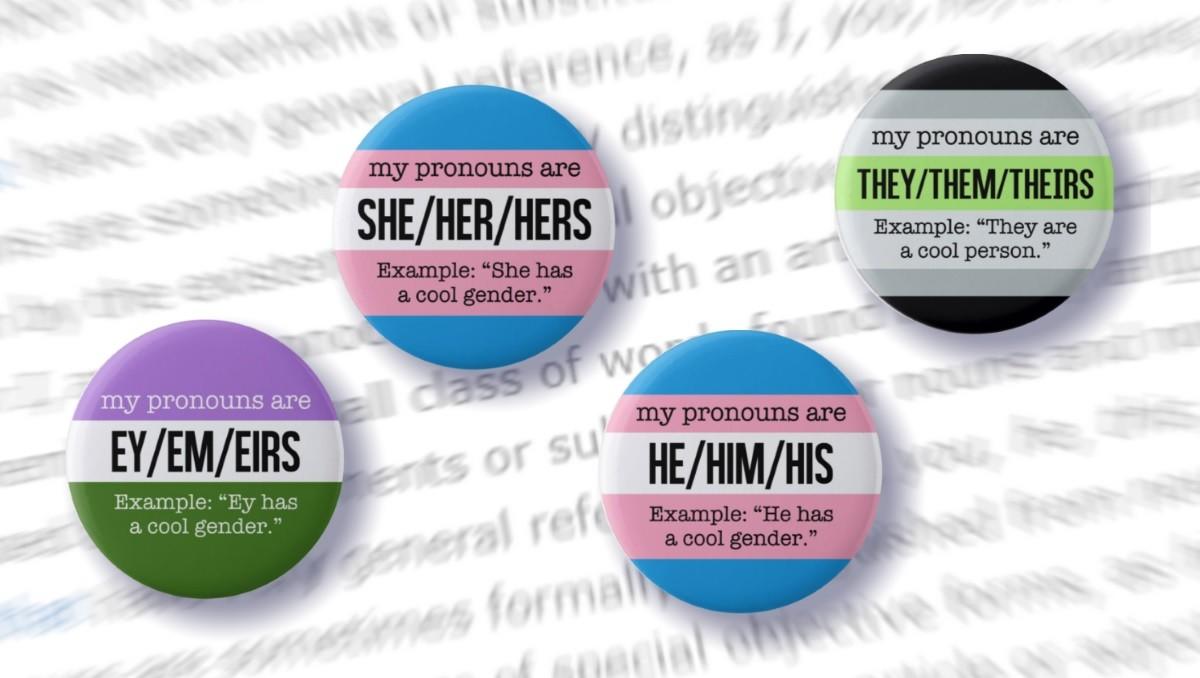

The gender identity movement has spread from elite bastions of higher learning such as Harvard and Wesleyan to the Walmart nearest you. The giant retailer announced this month that it will allow employees to wear buttons that declare their preferred pronouns. The choices are He/Him/His, She/Her/Hers, and They/Them/Their. Those who prefer Ze/Zir, Mx, or some other variant can wear the “Ask me my pronoun” button, presumably aimed at customers who feel the need to know their salesperson’s or cashier’s gender identity.

Walmart’s move is the latest sign of how “preferred pronouns” have taken root the United States, Canada, Britain, and some non-English-speaking countries. In France, for example, some people are proposing using “iel” or “ille” ‒ a combination of the masculine “il” and the feminine “elle,” to refer to non-binary people. In the United States, it’s becoming normal practice for schools and colleges, hospitals, media, and government and corporate offices to use the singular “they” or other recently coined pronouns.

IBM is among the companies that allow employees to specify their preferred pronoun in their human resource files. Forbes magazine reports on a move to encourage everybody to use them in email signatures ‒ a good thing, as one advocate of the practice said, because “it normalizes discussions about gender.”

Establishment institutions, from the Associated Press and The New York Times to the American Psychological Association and the New York City Commission on Human Rights, are endorsing the use of “they” in the singular to refer to individuals who may be transgender or just do not identify as either male or female. The Merriam-Webster dictionary named “they” the Word of the Year for 2019, meaning that it was the most looked-up word on the organization’s website (“quid pro quo” and “impeach” were in second and third places).

“The singular they and its many supporters have won, and it’s here to stay,” Jen Manion, an associate professor of history at Amherst College, wrote approvingly in a recent op-ed in The Los Angeles Times.

In other words, yet another practice that existed for years mainly on the social and intellectual margins ‒ in places like college diversity and equity offices, avant-garde theater collectives and LGBTQ circles ‒ has very rapidly gone mainstream. And this has happened much faster than other ideas that have moved from the “woke” periphery to the center of the national consciousness, such as gay marriage, or the dismantling of Confederate monuments, or removing the names of historical figures who owned slaves from university plaques.

Preferred pronouns have become virtually de rigueur with such remarkable velocity that much of the rest of the society hardly even noticed, much less had an opportunity to debate the trend and weigh its merits. A 2018 Pew Research Center survey found that 40% of adults agree that there should be more gender options besides just male and female.

As the British essayist Douglas Murray points out in his book, “The Madness of Crowds,” it took decades to go from “acceptance that homosexuality existed … to the position where gay marriage was legalized.” But “trans has become something close to a dogma in record time.”

How did this happen so fast? No doubt, one reason for the acceptance of preferred pronouns is that they are presented as a matter of common courtesy. People should be called what they wish to be called, goes the common-sense judgment, and to refuse to do so seems gratuitously rude. Store managers at Walmart or human resource personnel at IBM are probably not avatars of “wokefulness.” Their companies are simply responding to a demand, couched in the language of diversity, inclusion, and tolerance, that is difficult to resist.

And yet the rapid acceptance of preferred pronouns tends to blur important issues, ranging from the syntactical integrity of the English sentence to freedom of expression to biological reality.

“As a private matter, when it’s just me and another person, of course I’m going to use the pronoun they ask me to use, but I have a problem when it becomes a matter of public enforcement, which is a distinction that a lot of trans advocates miss,” said Libby Emmons, a writer and member of a radical feminist group, the Women’s Liberation Front, which has been the target of considerable fury from the censorious left. “This should be a matter of personal choice. I shouldn’t be forced to say or not say anything at all.”

Emmons and others are raising essentially two questions about preferred pronouns. One is that the often intense social, and sometimes legal, pressure to use them is a coercive impingement on free speech. The second is that preferred pronouns are an ideological wedge, a seemingly innocuous way of opening the door to a set of leftist identity-politics ideas that are highly debatable.

Although gender-neutral pronouns have flourished only recently, they have a longer history. Transgender people have been advocating alternative pronouns at least since 1996, when the writer Leslie Feinberg, in the book “Transgender Warriors,” used s/he or hir to replace the standard he or she.

The movement percolated through the years first inside the LGBTQ subculture, then among sexuality and gender studies departments at colleges and universities. Next, it was picked up by the equity and diversity offices that have proliferated at practically every institution, and now more widely by human rights commissions, media organizations, religious institutions, Walmart, IBM, Amazon, and many others.

And so, for example, after a three-year discussion of the issue, the University of Minnesota Senate, not generally a bastion of leftwing radicalism, voted last fall to allow all members of the university to specify pronouns of their choice, and to have access to “university facilities that match their gender identities,” meaning bathrooms, locker rooms, and sports teams, among others. The senate, which consists of faculty, staff, and student representatives, acted on a proposal made by the university’s Office of Equal Opportunity and Affirmative Action, along with the Gender and Sexuality Center for Queer and Trans Life.

The debate included objections to suppressing free speech, said Joseph A. Konstan, a professor of computer science and engineering and past chairman of the executive committee of the university senate. But, he told me in a phone interview, “we also heard from students who feel that First Amendment protections are an excuse to hold people down.”

In the end, the proposal passed when all mention of punishment, such as treating “misgendering” as a form of harassment or discrimination, was taken out of the text. “We wanted to focus on treating people with respect, addressing them the way they want to be addressed,” Konstan said.

Or as one student put it to the Minnesota Daily newspaper, “It’s just very invalidating when you tell somebody what you want to be referred to as, and they completely ignore that. That’s obviously not a safe environment.”

To what extent schools are obligated to make people feel “validated” and “safe,” rather than to be open to ideas that challenge assumptions, is, of course, hotly debated. That’s one reason the quick acceptance of preferred pronouns has provoked some familiar accusations ‒ that the unelected commissars of diversity, acting on behalf of an extremely small minority, have managed, again, to impose a set of restrictions and obligations on the rest of us. Surveys suggest that about 0.6% of Americans identify as transgender, but almost 2% of high school students do. It is not clear whether this disparity reflects the freedom of trans youngsters to proclaim their identity or if many are embracing it as they navigate the sexual confusion of puberty.

Perhaps the leading international dissenter on the issue is Jordan B. Peterson, a clinical psychologist, best-selling author, and YouTube activist at the University of Toronto. His opposition to preferred pronouns was initially prompted about three years ago by a proposed addition to Canada’s human rights law banning discrimination based on “gender identity.” Peterson argued that the provision would require what he calls “compelled speech,” forcing people to use certain words rather than others.

Several Canadian legal scholars said the law did not make “misgendering,” as the refusal to use preferred pronouns is sometimes called, an actual criminal offense. Still, even Peterson’s critics acknowledge that the letter sent to him by his university, warning that “misgendering” could be considered a form of discrimination under Ontario’s provincial human rights code, could reasonably be deemed intimidating.

Peterson’s visibility on YouTube, especially, has given him veritable international celebrity status – some hail him as a global anti-political correctness warrior, while others vociferously protest his appearances, vilifying him as “transphobic” and even neo-Nazi.

During one televised discussion on Ontario television, a fellow panelist and University of Toronto faculty member said Peterson’s refusal to use transgender pronouns was “tantamount to abusing students and violence.” Others invited on the program refused to participate, saying that would give legitimacy to Peterson’s retrograde views — in other words, that even to raise questions about the topic is morally illegitimate. In reporting this story, I spoke to one American transgender activist, who has a position in the LGBTQ equity office at a major university, who said that while nobody should be forced to say anything, the arguments against preferred pronouns are based on “hate and ignorance.”

“They deserve to be in public as much as the KKK or neo-Nazis do,” said this person, who declined to speak for attribution.

Those who question the preferred pronoun movement say such harsh rhetoric seeks to silence debate about the line between feelings and science.

“The very act of stating your preferred pronoun is a capitulation to an ideology,” Emmons said. “It is that a person can claim a biological identity based on emotion, that a person’s emotional feeling supersedes a person’s biology.” Implicitly at least, the demand for preferred pronouns, Emmons and others argue, is also a demand to recognize that a person with a penis and a beard can claim to be “non-binary” or a woman, even as some legislation is protecting that claim as a human right.

“This is a top-down ideological enforcement situation,” Emmons continued, “and I don’t want to be forced to say that a man is a woman.”

This is not a mere theoretical concern. The legal guidance on gender discrimination from the New York City Commission on Human Rights, for example, “requires employees and covered entities to use the name, pronouns, and titles (e.g. Ms./Mrs./Mx.) with which a person self-identifies,” or be subject to fines that can go as high as $250,000.

In 2018, the human rights commission brought charges against Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital for indirectly asking a person claiming to be a transgender woman whether he (or should that be she or maybe they?) had a penis, and, apparently suspecting that he did, insisting that he stay in a private room rather than be housed with a female patient. The hospital was fined $25,000 in “compensatory damages” paid to the transgender woman and was required to “update its system to make patients’ preferred names and pronouns visible to frontline staff.”

There are other examples indicating that preferred pronouns are no longer an optional, personal choice. At Shawnee State University in Ohio, a 62-year-old philosophy professor, Nicholas K. Meriwether, was warned by the school administration that his refusal to use transgender pronouns was a violation of the university’s non-discrimination policies.

At Duke University Hospital in Raleigh, N.C., emergency room physician Kendall Conger received a letter from the hospital’s committee for inclusion and diversity accusing him of creating a “negative environment” after he told a student that wearing a pronoun-identifying badge on her lapel might make some religious patients uncomfortable.

In England a couple of years ago, a high school math teacher in Oxfordshire was suspended after he refused to refer to a transgender girl as a female on religious grounds.

There do not appear to be broad studies indicating whether such anecdotes are part of a larger pattern of penalties for the refusal to use the preferred pronouns. But the fact that they are imposed on a practice that only a tiny cultural subgroup had even heard of just a few years ago is a measure of the extraordinary velocity with which it has become a moral norm. A survey conducted by the Pew Research Center late in 2018 found that one in five American adults knows somebody who goes by a gender-neutral pronoun, which, given how new the trend is, seems like a rather large number.

Pew also found that among people 18 to 30, three-quarters have heard about people wishing to be referred to by “non-binary pronouns.” And slightly more than half of Americans say they are “comfortable” with that.

All of this is so new that some questions seem not to be getting much attention, among them, whether the ever more intense effort at a gender-diverse language is an affront both to grammar and precision. Take the sentence, “Mary had no food in the house so they got take-out for their children.” The possessive “their” to refer to one person certainly seems a bit jarring, at least to people not used to it. It’s also ambiguous, unclear as to whether Mary got take-out by herself or was accompanied by somebody else, perhaps the children. Using “her” might be decried by trans advocates as insulting and discriminatory to Mary, but at least it would present no such problems.

Beyond that, how does one even know that Mary’s preferred pronoun is they/them/their? Will everybody have to keep records in their smartphone directories of each contact’s preferred pronoun? Will people really refer to Mary as “they” when talking in Mary’s absence, as in “Mary told me they’re reading a new book and they love it”? Will the turn to preferred pronouns require changes in legal documents?

None of this seems to have been thought through very carefully, even as preferred pronouns are becoming fashionable, a chic new thing, one that, from all appearances, is here to stay.

Tyler Durden

Fri, 03/20/2020 – 22:45

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2U52ws6 Tyler Durden