Minerd: “How Do We Know We Haven’t Reached The Bottom? When The Talking Heads On CNBC Are Buying”

Guggenheim CIO Scott Minerd hasn’t been exactly bullish in recent weeks. In fact, the weightlifting asset manager, best known perhaps for repeatedly warning about the corporate bond bubble and the threat of fallen angels, last month prudently cautioned that “we’ve reached the tipping point“, and that the coronavirus will deflate the everything bubble. Four weeks later he has been proven correct.

So with stocks down 35% from their all time highs set around the time Minerd made his warning, is the CIO ready to flip and start buying stocks as some of his more vocal hedge fund peers such as Jeff Gundlach and David Tepper?

The, as two of his latest tweets reveal, is a resounding now. Warning that “Bottom fishing is still the most expensive sport in the world”…

Bottom fishing is still the most expensive sport in the world.

— Scott Minerd (@ScottMinerd) March 23, 2020

… and that we will not reach a bottom as long as the talking heads on CNBC are buying…

How do we know when we have not reached the bottom? When the talking heads on CNBC are buying.

— Scott Minerd (@ScottMinerd) March 23, 2020

… overnight Minerd published another report to clients titled “The Great Leverage Unwind”, in which he warns that “funding and trading markets are not functioning well due to excessive leverage needing to be unwound in the financial system” and summarizes what lies ahead by sayng that “we will likely experience something that is just as severe as, if not worse than, the financial crisis.” How to invest? As we said late last night, “I expect corporate bonds and other fixed income assets would give higher returns than equities on an absolute basis, not just a risk adjusted basis.” In light of today’s blistering outperformance of corporate bonds now that the Fed is backstopping investment grade, his trade reco is already quite profitable.

His full note is below, highlights ours:

The Great Leverage Unwind

We entered into the current crisis with a whole financial system that had been incentivized by policymakers to take on excessive levels of debt and leverage. The turmoil we are seeing right now is the result of the unwinding of this leverage. The primary catalyst of the turmoil is the collapse in economic activity due to the COVID-19 shutdown, but the fact that funding and trading markets are not functioning well is due to excessive leverage needing to be unwound in the financial system.

The first order of that unwind is what we have been seeing over the last week or two, where hedge funds and mutual funds are in a mad dash to get to cash.

While I think the Federal Reserve (Fed) is doing a pretty good job at helping to keep the financial system functioning as smoothly as possible, I don’t think we are out of the woods. There will likely continue to be announcements of additional programs and changes in operating procedures at the Fed. I also expect further announcements out of the White House on policy implementations. In order to get a foundation under the markets, we’re going to need something very large, something in the $2 trillion range in the form of a pool of liquidity that can be made quickly available to businesses and corporations that need it, along with the financing facilities of $2 trillion–$4 trillion from the Fed. A structure like this will be much more efficient than a targeted approach of trying to engineer bailouts industry by industry, which would just take too long.

In addition to Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP)-like programs to assist companies and industries, there is no other choice but for the Fed to step up to keep markets functioning. That’s why I’ve been saying that we would need to see about $4.5 trillion of quantitative easing (QE) before everything was resolved. This is in addition to emergency lending through the discount window, dealer repo operations, central bank liquidity swaps, and the Commercial Paper Funding Facility, Primary Dealer Credit Facility, and Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility. That would take the Fed’s balance sheet to at least $9 trillion, or about 40 percent of last year’s gross domestic product (GDP). That might sound like an alarmingly big number, but to put it in perspective the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet is the equivalent of 105 percent of GDP. So, the United States is a piker on QE.

I see a number of trouble spots in the markets. There are many highly leveraged firms that are in the crosshairs of the economic shutdown, including airlines, lodging, retailers, and energy. These vulnerable industries are in the midst of a massive dislocation.

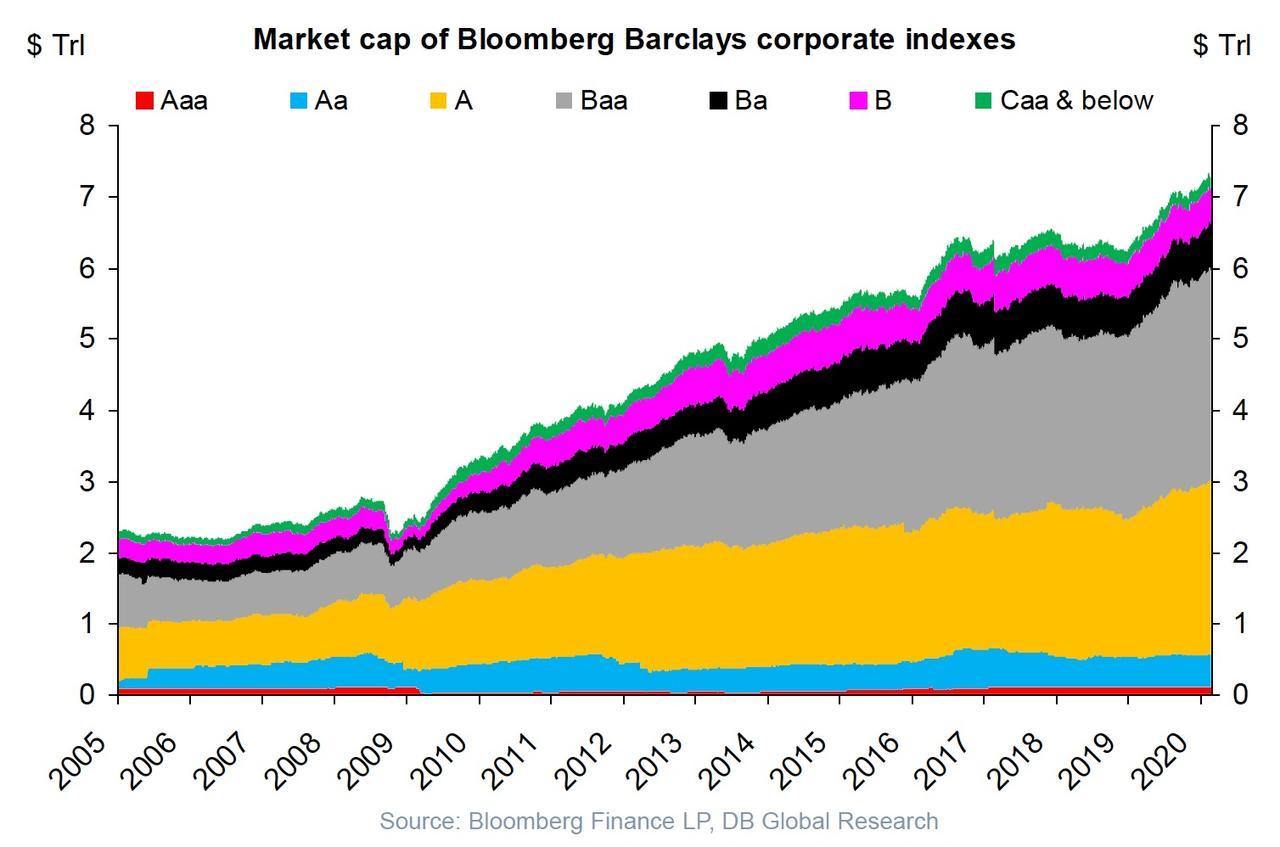

BBB-rated corporate bonds, which make up a majority of the investment-grade corporate universe, are also a major concern. Many of these BBB-rated companies don’t pass the criteria to be rated BBB by the rating agencies. The rating agencies, however, have shown forbearance by adopting a more liberal interpretation of either cashflow coverage or asset coverage, and accepting promises that these companies will de-lever. Kraft-Heinz is a good example of what happens when the rating agencies, confronted with the fact that Kraft-Heinz wasn’t making the progress it promised, downgraded the company to BB.

There are approximately $1 trillion worth of investment-grade corporate bonds that are in danger of being downgraded like Kraft-Heinz. Currently, the high-yield market has approximately $1 trillion outstanding, meaning the size of these possible downgrades would double its size. I do not believe that the current concessions on high yield in terms of their spread to Treasurys or absolute yields is sufficient to clear that supply.

Who are the marginal buyers that can pick up that much supply? There might be some investors who, like Guggenheim, have been conservative and have some capacity to add risk. But the real capacity, I believe, is going to reside in the land of private equity (PE), where firms have raised commitments of over $1 trillion for their funds. When PE firms are able to step in and buy high-yield bonds at 15–20 percent, and then they have the ability to lever those positions, that becomes an attractive alternative to private equity.

On a more sector-specific level, the asset securitization market is essentially not functioning. During the mini-recession of 2015–2016, when oil traded down to a low of $26 a barrel, the BB tranches of collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) were trading around 40 cents on the dollar, and BBB tranches around 60 cents. Today, there are a lot of sellers in this asset category, but they are offering 80 cents on the dollar for BBB and 70 cents on the dollar for BB. We are headed to a more severe downturn than we experienced in 2015–2016. Capitulation has not occurred in the CLO market.

This reluctance to capitulate is not an uncommon phenomenon. A lot of investors hang on to positions and hope. Occasionally a blind squirrel will arrive and buy at a non-market price, but as the supply of CLO assets that need to be sold continues to increase, the prices are slowly (or rapidly) going to start coming down.

Many sellers today are what I call securitization tourists. These are the hedge funds, insurance companies, pension funds, and others who, in their great search for yield over the last two to three years, kept reaching for it in securitizations. They didn’t have the real expertise that is needed to invest in the sector, they were kind of just visiting. A lot of the people who have jumped into securitization as a way to enhance their yields are now finding themselves having to unload positions. They will have to capitulate soon.

Aircraft securitizations, which are secured by airplane leases from airlines, are in trouble. Airlines are going to face the reality that they either default on their lease payments or ask for forbearance as air travel grinds to a halt. Lessors are already getting a lot of requests for forbearance, but as business conditions continue to deteriorate some carriers will file for bankruptcy or liquidation and have to sell aircraft. Today, the price for a used commercial aircraft is close to zero. That is lower than the price at which airplanes were selling post-9/11. The 9/11 event was mostly a U.S. event and foreign carriers were not dramatically affected. This is the first time that we have a global incident where carriers all over the world are basically shutting down their air travel at a level even lower than the great recession of 2008–2009.

Interestingly, aircraft securitizations have not moved into the realm of pricing that would be appropriate. Investors are offering securitizations at 85 or 90 cents on the dollar, when many securitizations reasonably should be worth 50 or 65 cents on the dollar, or maybe lower.

As these and other markets are not clearing, we have not seen capitulation in the credit markets, even though we have already had massive spread widening in investment-grade and high-yield bonds. To put this spread widening in context, corporate credit spreads relative to U.S. Treasurys have been wider than where they are today just 2 percent of the time. This is good value, but value is a poor timing tool. Things that are cheap can get cheaper. The 2008 wides in investment-grade corporate spreads were 618 basis points, about 250 basis points wider than where we are right now.

Since we haven’t seen capitulation yet, it would be premature to step in and buy aggressively at current levels, whether it is stocks or credit assets.

In terms of the economy, any policy program is good if it can help prop up households that need help to make mortgage payments, pay utility bills, or make car payments. More than 50 percent of Americans have less than $500 in savings, so it is going to be difficult for low wage earners who are living hand-to-mouth, earning maybe $2,000 or $3,000 a month, to stay current on all of their commitments even if they are handed a check for $1,000 from the U.S. Treasury.

Rather than speculate about which emergency economic rescue programs are good or bad, let’s just put it this way: In the financial crisis, Congress passed TARP in October 2008, well before the market bottomed. After the ensuing turmoil, we didn’t really hit bottom until March of the following year. Even if Congress passes all of the necessary legislation, we should be expecting that the market will be vulnerable for another six months. This means that “buying the dip” on the expectation that Congress is going to pass something soon is probably not a prudent investment strategy.

Since we haven’t seen capitulation yet, it would be premature to step in and buy aggressively at current levels, whether it is stocks or credit assets.

Finally, I’m not an epidemiologist, but I have a few observations on the virus. I’m going to make a great leap of faith here and assume the Chinese government is releasing accurate data: In Wuhan the number of active cases peaked about 4 weeks after the lockdown after increasing roughly one hundred-fold. Pick whatever day you want for the starting point of the American version of the lockdown—pick St. Patrick’s Day or lockdown day in California—but I expect that the epidemic will continue to worsen over the course of the next three or four weeks if we follow the Wuhan pattern of the growth in cases, which virtually every country in the world has followed. This means we would have 100 times as many cases in the United States as we had from lockdown date. That means there could be 2 million identified cases in the United States in a month. That tells us our living patterns are not going to return to normal in the next 30 days, especially since we have not locked the entire country down yet.

If there is a risk to what I’m saying, the risk is that it will be worse, not better. That is why I made the statement that if the policymakers don’t handle this crisis appropriately and swiftly there is a 10–20 percent chance that we face a global depression. Now that means there is also an 80–90 percent chance that we are not going to have global depression. If you’re an investor, the odds are in your favor. I’m not betting on a global depression, but I’m saying that for the first time in the post-war era we are really getting too close for comfort.

In 2006–2007, I talked about the possibility of an imminent financial crisis, but at the same time I also talked about the solution. The solution was that the Fed floods the system with cash, the government does a bunch of prop-up programs, and we come out of it. Here, I don’t know the solution. I can’t tell you how to fix the virus problem, or how long it will last, but this means that the unknown in the investment community and for the populace at large is a lot larger than it was during the financial crisis. And so, in all likelihood we will experience something that is just as severe as, if not worse than, the financial crisis.

I am an optimist at heart. When we finally get to a bottom, a lot of the distressed assets in fixed income will be really attractive. One of the observations I made during the financial crisis was that, for the first time in my career, I actually thought that corporate bonds and other fixed-income assets would give higher returns than equities on an absolute basis, not just a risk-adjusted basis. I expect we will see this in the current situation as well.

Fundamentally, we will change the way the economy works. Consider how people and companies are adapting to the work-from-home operating standard. It’s a lot cheaper to have employees work at home instead of in an office. At some point companies will choose to not have certain employees commute to the office, sometimes an hour and a half in each direction. Having employees work from home allows for a couple of extra hours to work and more time for families. This will impact demand for commercial office space in a dramatic way, and obviously the knock-on effects will be to retailers, restaurants, and other ancillary industries while the virtual world will do very well.

We will eventually get out of this in the next three to four years—and I’m not suggesting we will be in a recession for three or four years. I expect that the recession will last somewhere between six and 18 months. This is a big time gap, but until we get the economy running on all cylinders again, where the lodging, airline, and energy industries, along with other affected industries, are back to the level where we were just a few months ago, it’s probably going to take about four years. In the meantime, a lot of debt has to be unwound or restructured. This will result in the Fed having to keep the liquidity spigots open for a long time.

Tyler Durden

Mon, 03/23/2020 – 17:05

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3bkPxYX Tyler Durden