The Lessons Learned From Today’s Disastrous Global PMIs

There have been a number of PMIs released in the last 12 hours or so… And it’s safe to say that they didn’t live up to expectations, exposing how thankless a task it is to forecast economic data in this environment.

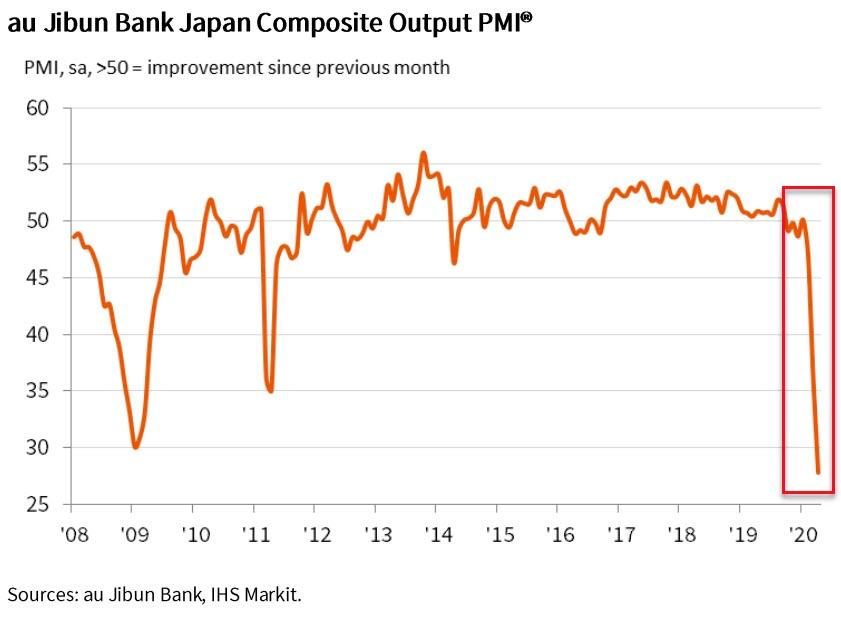

Japanese PMIs hit record lows (well below expectations)…

Europe was a bloodbath (plumbing depths hardly any economist expected)…

And now preliminary April data for the US was a utter disaster…

-

Flash U.S. Services Business Activity Index at 27.0 (39.8 in March). New series low.

-

Flash U.S. Manufacturing PMI at 36.9 (48.5 in March). 133-month low.

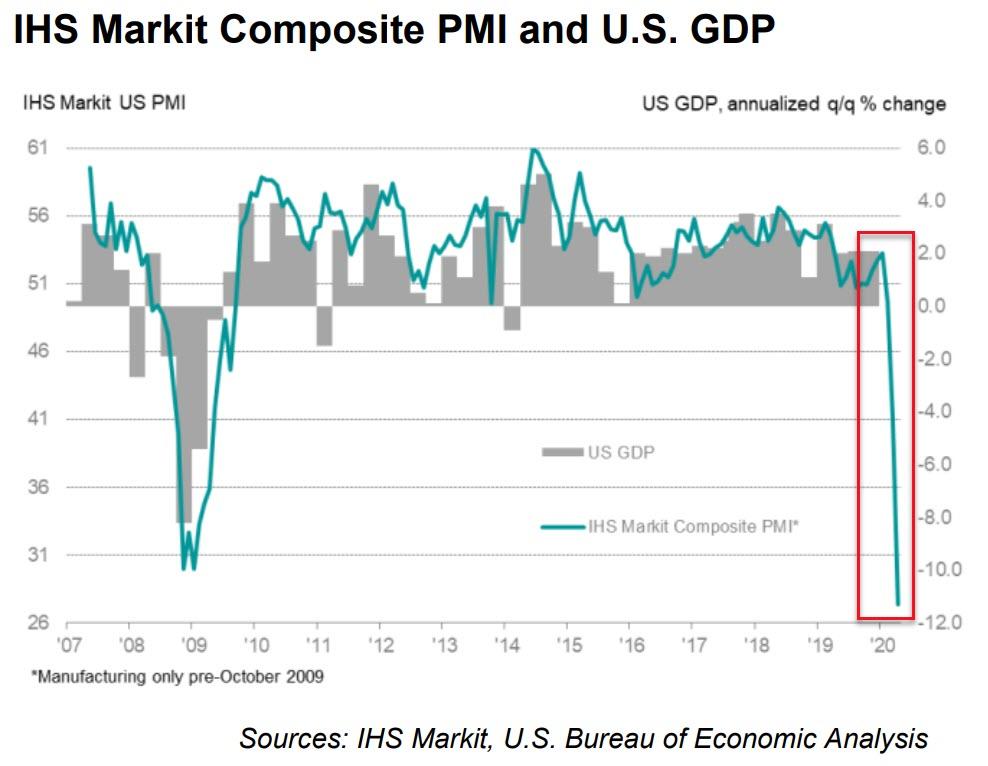

The US Composite PMI crashed to a record low at 27.4 as China bounces back miraculously…

Commenting on the flash PMI data, Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist at IHS Markit, said:

“The COVID-19 outbreak dealt a blow to the US economy of a ferocity not previously seen in recent history during April. The deterioration in the flash PMI numbers indicates a rate of contraction exceeding that seen even at the height of the global financial crisis, with jobs also being slashed at a rate far exceeding anything previously recorded by the survey.

“The large swathe of non-essential business that has been shut down temporarily amid efforts to contain the virus means the blow has been most heavily felt in the service sector, and especially for consumer facing companies in the recreation and travel industries. Those companies still actively trading meanwhile reported the steepest drop in demand seen since data were first available, and are also struggling against twin headwinds of staff shortages and supply chain delays.

“The scale of the fall in the PMI adds to signs that the second quarter will see an historically dramatic contraction of the economy, and will add to worries about the ultimate cost of the fight against the pandemic.”

However, as Bloomberg’s Richard Breslow notes, the PMIs also raise some interesting questions… and answer a big one.

First of all, you have to wonder why there has been a consistent pattern of misses versus forecasts. The cynic in me would suggest that it might be wise to take whatever number the models suggest and just apply a haircut. But while that may be useful in establishing bragging rights for coming closer to predicting the actual outcome, there is a real value to benchmarking where we actually stand versus what might have previously been reasonable expectations. This is an example of when being right is of less value than knowing just how much current reality and past norms of economic understanding differ.

Another question is why the models continue to look for results that are better than the actual outcomes. This probably has a lot to do with the perennial issue of asset prices not reflecting real life. Models look at the equity and credit markets, among other things we are being forced, or at least encouraged, to keep buying, and guessing wrong on what it “must” mean. We know that there are two alternative universes out there. That’s a very hard hard reality to teach to a model that can’t help but use correlation matrices and data time series that, in the realm of economics, have to go back a long way to be useful.

This is yet another reason to retire the hackneyed use of the phrases “risk-on” and “risk-off.” It’s probably far more accurate to say “More buyers than sellers today” or the opposite, as the case may be. Front-running a central bank doesn’t require an assessment of the state of the world. Or necessarily imply what it appears to look like.

We know things are tough out there. Using diffusion indexes, as we did today, to measure it adds an extra layer of uncertainty. Is anyone going to respond that things are certainly looking up? Even businesses that are doing well in this environment are loath to crow about it. “This pandemic is great for business” may be true in some cases, but it’s something better kept in-house. Circumspection is far more appropriate. And leave it to investors and lenders to figure out the winners and losers for themselves. We should also take the disappointments of the forward outlooks with a grain of salt. It’s so virus-dependent as to be not a very useful data point. It’s like asking about inflation expectations when rates are zero.

Yet interestingly, markets had modest but noticeable reactions to the releases. Which, at first blush, seemed a bit surprising. There have been more important numbers, with equally bad misses, that came and went unnoticed by traders. Just think back to the head-scratching response to some of the claims numbers. The reason these latest numbers provoked a response could very well be that traders are people, too. And we’ve allowed ourselves the luxury of hoping things are getting better faster than they really are..

It’s felt good to talk about relaxing restrictions and the possibility of opening some things up. We want that to happen. Boy, do we. So when bad numbers reminded us that we may be getting ahead of ourselves, it hurt. Nothing cataclysmic. But it was there, nevertheless. And, it may have been a cheap, yet valuable reality check. I know, I was disappointed with the outcome. And I wasn’t expecting much. It’s hard to argue these were simply backward looking measurements.

It’s an important reason, and this should be the unpleasant lesson learned, that we need to be very careful as we try to move toward normality. No one wants to be able to more than me. But, moving too quickly and having to step backward will hurt a lot more than being cautious now. And, potentially, do a lot more economic damage than already being experienced. Talk about a potential blow to morale. There might be light at the end of the tunnel, but we’re still in it.

The cure isn’t worse than the disease. I’m not at all sure this is really a states’ rights issue given we all have a stake in the matter.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 04/23/2020 – 09:50

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3eHrQwt Tyler Durden