A Potemkin Market Exposed – Howard Marks Fears The Fed Can’t Fake-It Forever

Tyler Durden

Mon, 05/18/2020 – 12:45

As everyone is well aware, today we’re experiencing unprecedented (or at least highly exceptional) developments in four areas: the pandemic, the economic contraction, the oil price collapse and the Fed/government response.

Thus, as Oaktree Capital’s Howard Marks recently wrote, despite the US stock market’s apparent exuberance, a number of considerations make the future particularly unpredictable these days:

The field of economics is muddled and imprecise, and there’s good reason it’s called “the dismal science.” Unlike a “real” science like physics, in economics there are no rules that one can count on to consistently produce a given outcome, as in “if a, then b.” There are only patterns that tend to repeat, and while they may be historical, logical and often-observed, they’re still only tendencies.

In some recent memos, I’ve mentioned Marc Lipsitch, Professor of Epidemiology at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health. In my version of hierarchy, there are (a) facts, (b) logical inferences from past experience and (c) guesses. Because of the imprecision of economics, there certainly are no facts about the economic future. Economists and investors make inferences from past patterns, but these are unreliable at best, and I think in many cases their judgments fall under the heading of “guesses.”

These days, I’m often asked questions like “Will the recovery be V-shaped, or a U, W or L?” and “Which of the crises you’ve lived through does this one most resemble?” Answering questions like those requires a historical perspective.

Given the exceptional developments enumerated above, however, there’s little or no history that’s relevant to today.

That means we don’t have past patterns to fall back on or to extrapolate from. As I’ve said, if you’ve never experienced something before, you can’t say you know how it’s going to turn out.

While unique developments like those of today make forecasting unusually difficult, the presence of all four elements at once probably renders it impossible. In addition to the difficulty of understanding each of the four individually, we can’t be sure how they’ll interact. For example:

Will the massive, multi-faceted Fed/Treasury program of loans, grants, stimulus and bond buying be sufficient to offset the unparalleled damage done to the economy by the fight against Covid-19?

To what extent will the reopening bring back economic activity, and to what extent will that cause the spread of the disease to resume, and the renewal of lock-downs?

For investors, the future is determined by thousands of factors, such as the internal workings of economies, the participants’ psyches, exogenous events, governmental action, weather and other forms of randomness. Thus the problem is enormously multi-variate.

As Marks asks, rhetorically:

“Who can respond to this many questions, come up with valid answers, consider their interaction, appropriately weight the various considerations on the basis of their importance, and process them for a useful conclusion regarding the virus’s impact?”

Who indeed? Well, it would appear that as long as The Fed keeps printing, or promising to print, or promising that if things get worse it will print, everything will be awesome.

But Marks is not buying that. In a Bloomberg “Front Row” interview, the billionaire hedge fund manager asked “Can the Fed keep it up forever?”

“Those of us in the markets believe that stocks and bonds are selling at prices they wouldn’t sell at if the Fed were not the dominant force. So if the Fed were to recede, we would all take over as buyers, but I don’t think at these levels.”

And thus, the dilemma for policy-makers is no longer their mandate-driven balance of inflation and employment but the just how hard can we push the pedal to the metal to keep the wealth effect going before the engine explodes (or worse still, the financialized economy is exposed for the fallacy that is has become).

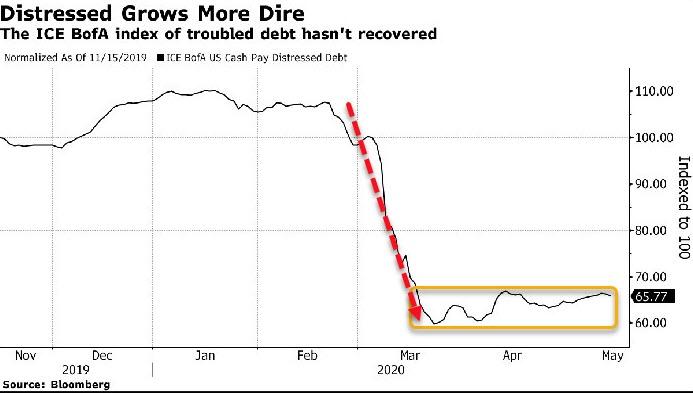

What happens, as Marks notes, when the funding runs out? (or if the funding runs out) and we have already seen credit markets – despite all the hype of Fed direct ETF intervention and issuance – are not drinking from the same Kool-Aid jug as the stock markets…

The mantra of “you can’t fight the Fed” appears to be ignored by credit overall, and Marks agrees – expecting a slow and halting recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and said “there will be plenty” of debt defaults and bankruptcies when corporate borrowers start running out of cash in the months ahead.

“There are large, highly levered companies and investment vehicles that the government and Fed rescue program is not likely to reach and take care of,” he said.

Specifically, Marks notes that while the central bank has committed to buying investment-grade bonds and debt recently downgraded to junk, it hasn’t extended that support to less-creditworthy issuers.

“They could do that,” Marks said.

“And in theory, if they bought aggressively, they could make all the markets rise. Now everyone would know that that’s a Potemkin market, a fake, and the minute they stopped things would collapse.”

Finally, in one of his recent memos to clients, Marks quoted a saying:

“Capitalism without bankruptcy is like Catholicism without hell.”

In the interview, he reiterated that fear, worrying that Fed support for the credit market will result in moral hazard – the likelihood that those who escape the consequences for reckless behavior will be reckless again.

As Marks summed up in his latest letter to investors, no one can succeed in predicting things that are heavily influenced by randomness and otherwise inconsistent.

Maybe Voltaire said it best 250 years ago: Doubt is not a pleasant condition, but certainty is absurd.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2TeR4cI Tyler Durden