Germany, Denmark Are Models For How To Reopen Schools In The Age Of COVID-19

Tyler Durden

Mon, 08/03/2020 – 17:05

With the fall semester officially starting this week in some parts of the US, the question of how public schools will reopen for the fall semester, and how much in-person learning to allow, if any, is weighing on the minds of millions of Americans.

And while we await to learn more about New York’s plans for reopening its schools, a team of economists at Goldman Sachs took a close look at the existing data surrounding the virus’s ability to spread in schools, and among younger children, along with the economic costs of keeping schools closed, in an attempt to answer a critical question: How exactly should the US go about reopening its schools?

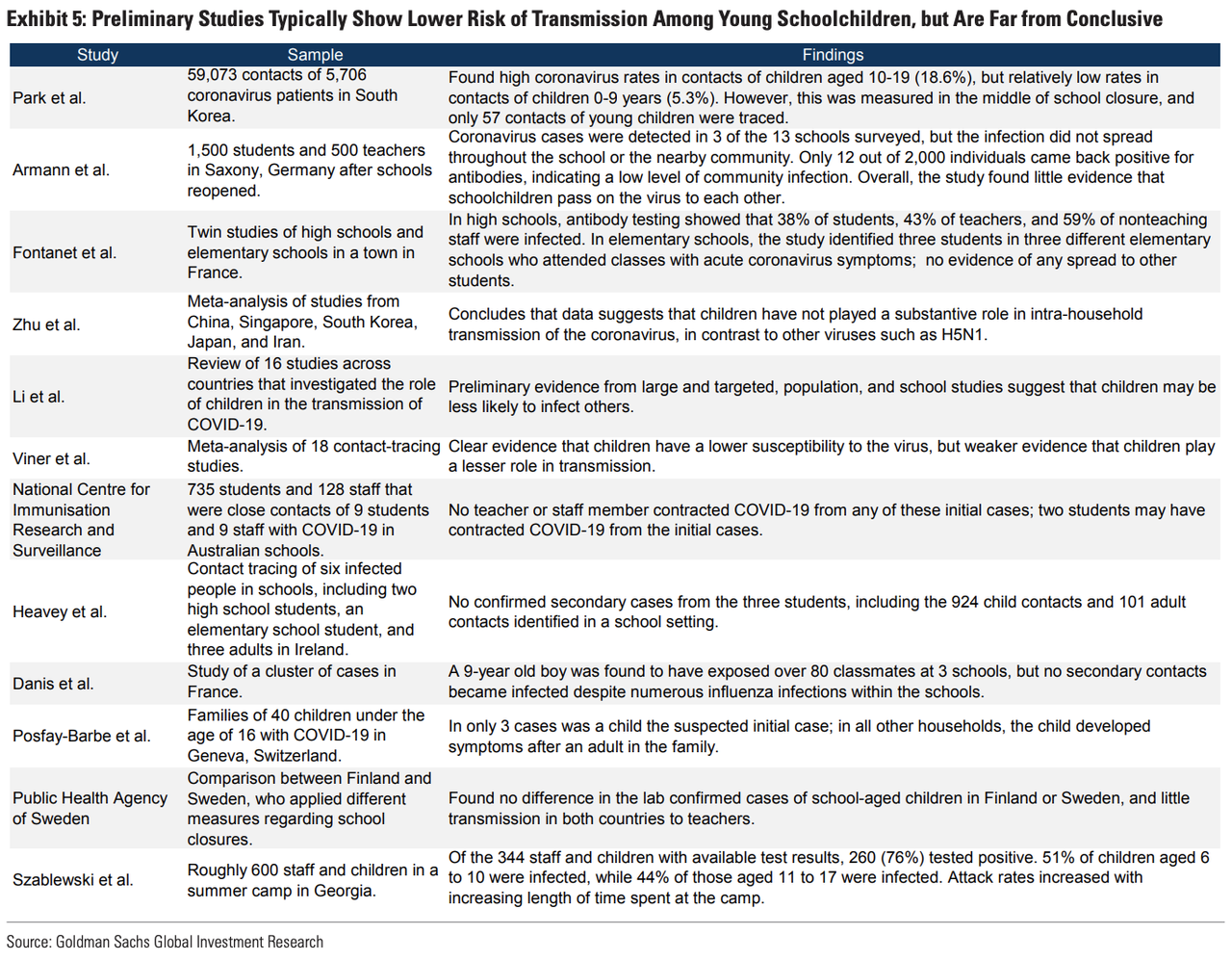

Looking at the problem from a strictly medical perspective is difficult enough. The research that exists is often contradictory. One large study based on comprehensive contact tracing in South Korea found that children under 10 were roughly half as likely as adults to transmit the virus to others, while children between the ages of 10 and 19 transmitted the virus at similar rates to adults.

Other studies appear to show children spreading the virus at similar rates to adults, including one study focusing on a summer camp in Georgia.

Another study found that children may carry higher viral loads, suggesting that they could put adults around them at high risk of infection.

It’s fair to assume at this point that children are at less risk of infection and death, but that’s about all we can say for sure. As always, the bigger problem is what are the societal ramifications in terms of infection numbers?

The usefulness of these studies is clearly limited. With that in mind, governments should instead look to the handful of examples where schools successfully have reopened without triggering the virus to come roaring back.

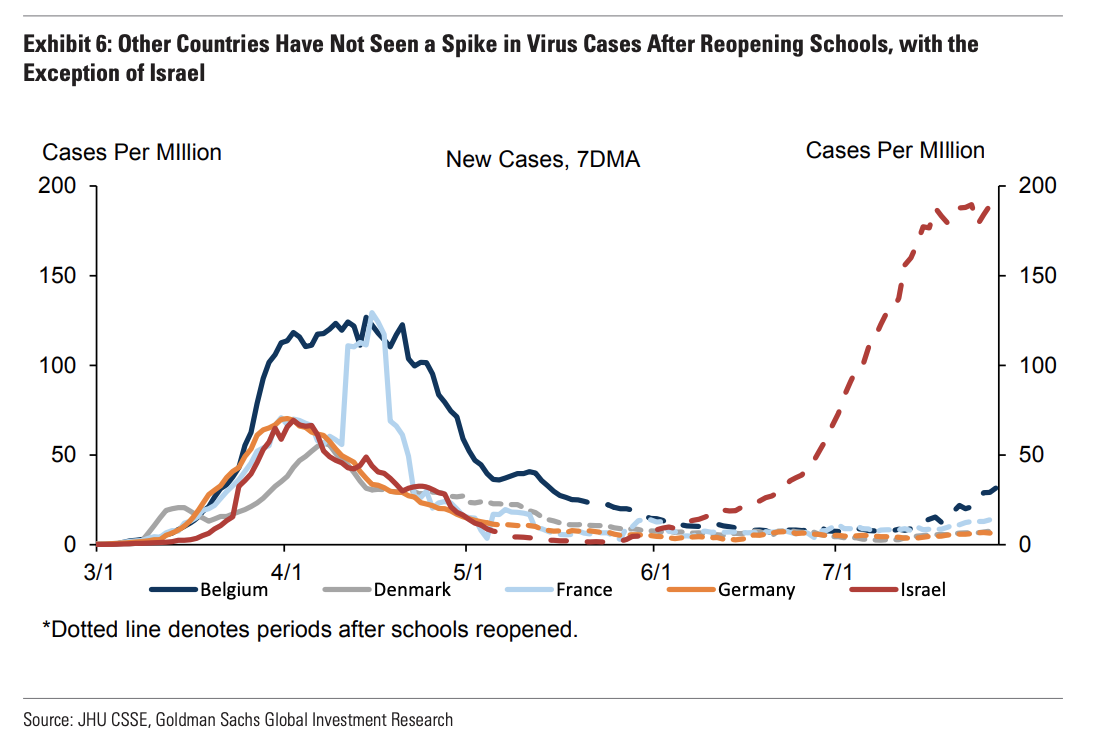

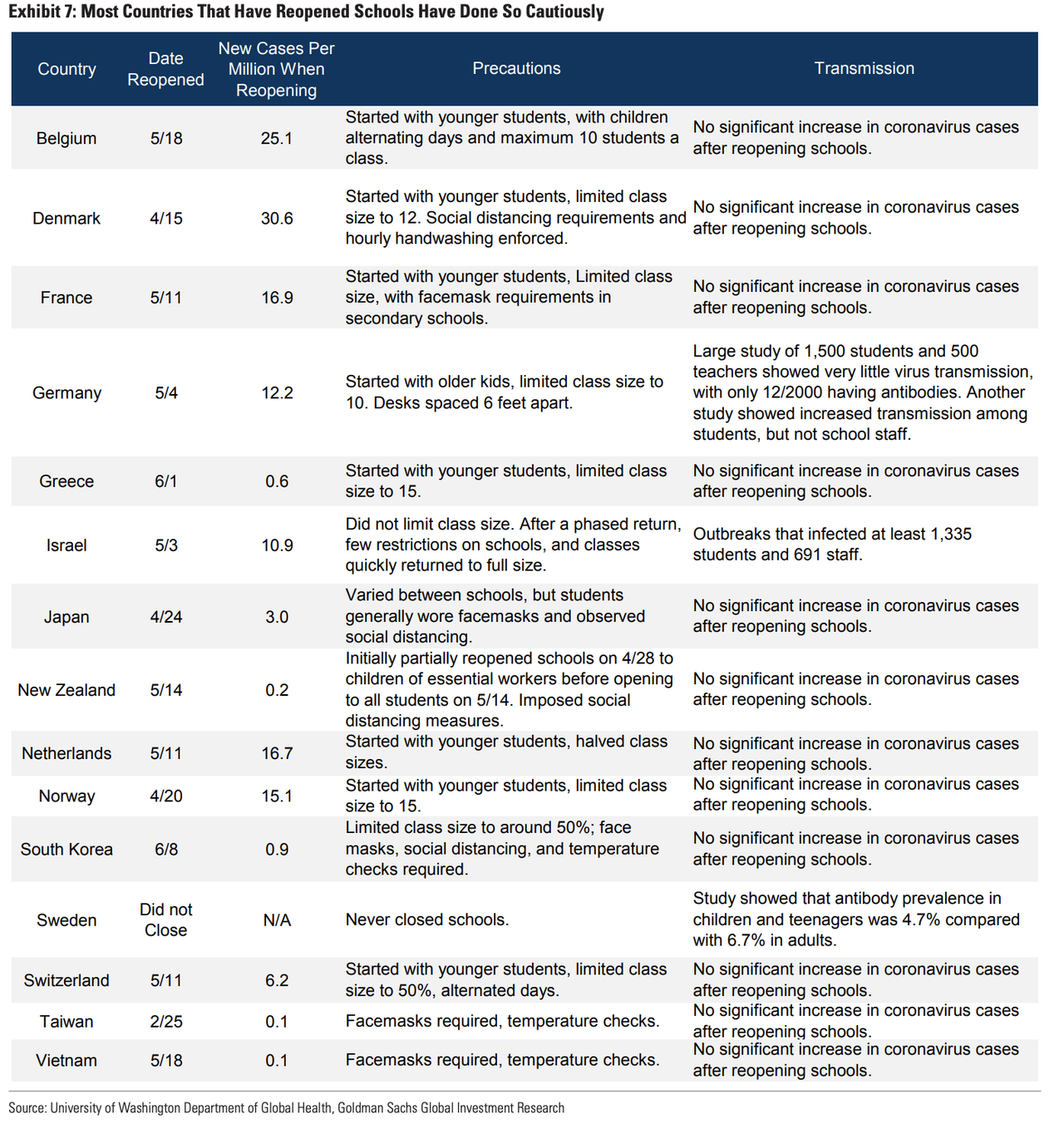

We’ve repeatedly cited the experience of Denmark as a potential guiding light for the US, and the rest of Europe, when it comes to reopening schools. Goldman takes this analysis a few steps further, looking at an even broader scope of countries that have reopened schools cautiously and carefully, despite having only limited numbers of the infected.

Still, Belgium, France and Germany certainly saw substantial outbreaks, even if the virus may not have penetrated as deeply, in as many parts of their countries, as it did in the US.

American states could probably learn a thing or two from the judicious approach favored by Germany, France and Belgium. And if that isn’t enough to drive home the point, Goldman argues that Israel’s approach stands in stark contrast to Europe: Israel reopened classes with as many as 40 students, and few restrictions. Cases quickly flared back up, suggesting that reopening must be carefully monitored.

Here’s a more detailed breakdown of how various countries approached reopening their schools.

Sweden, as Goldman points out, never closed its schools. And although it’s not a focus of the report, its example certainly warrants close scrutiny.

To be sure, the process of reopening schools in the US will require a much more detailed explanation. Approaches will vary widely from state to state, with Georgia, Indiana and a handful of other states pushing ahead with the return to in-person instruction, even as cases from the outbreak’s second wave have only just begun to decline.

But motivated by the second wave and parents’ lingering fears, a growing number of states are pushing back start dates for in-person learning. Some states have left the decision up to individual counties – and some counties like Miami-Dade have been steadfast in their opposition to pressure from the statehouse and Washington.

In many cases, local school districts will decide when to reopen.

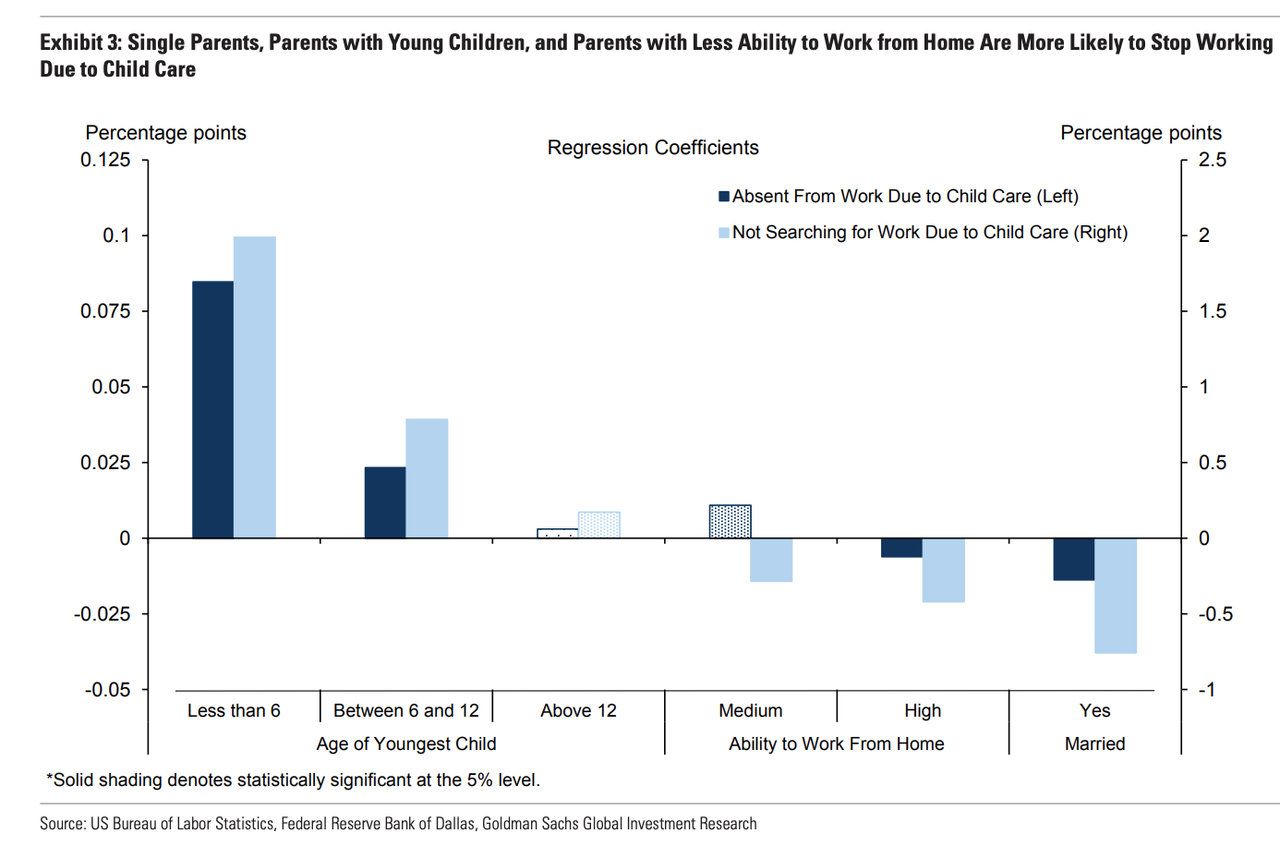

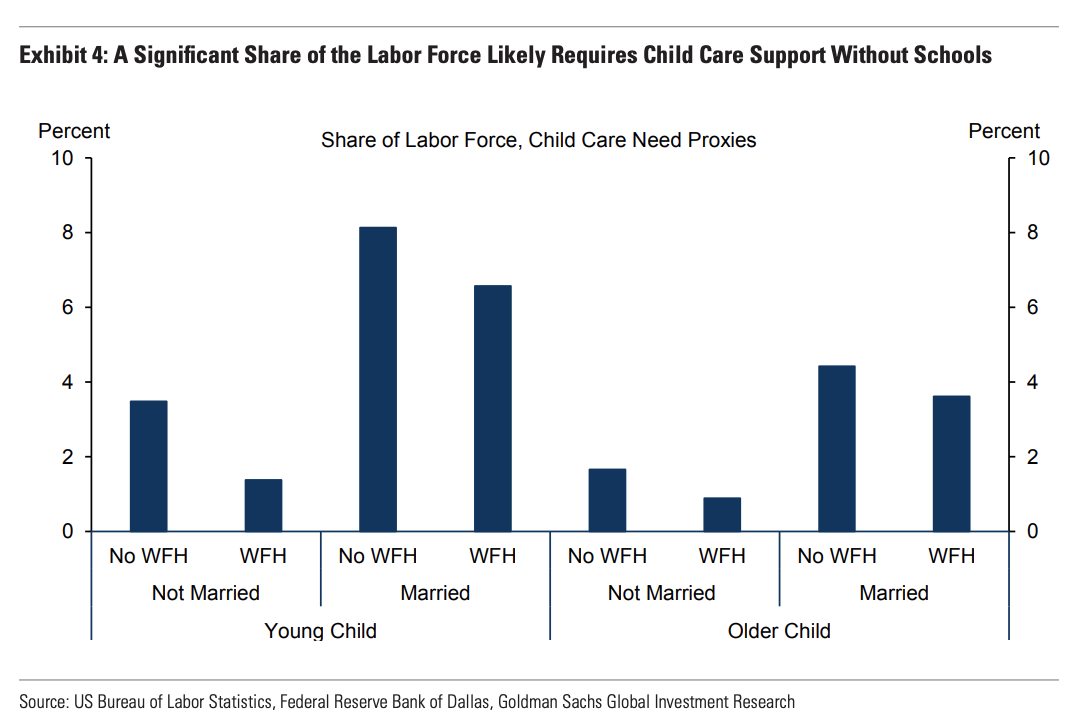

Like with many other aspects of the government response to the pandemic, keeping schools closed places the biggest strain on the most vulnerable members of society, especially single parents…

…but also married couples. Regardless, without schools open, a large chunk of the labor force will require support in the form of child care to make a return to full-time work plausible.

While keeping schools closed comes with a tremendous economic pricetag, since not only are educators out of work, but parents, too, struggle to secure affordable childcare, putting their jobs at risk. This can seriously suppress productivity and labor-market growth. But in the worst-hit states, the risks of thousands of preventable deaths are simply too great to justify pressing ahead.

Successfully reopening schools will ultimately depend less on infection rates among students, but on infection rates among parents, teachers and coaches.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2PjgXp5 Tyler Durden