Trump Versus Biden And The Transatlantic Trade Relationship

Tyler Durden

Sun, 11/01/2020 – 08:10

Authored by Maartje Wijffelaars and Philip Marey of Rabobank

Summary:

- A Biden victory could pave the way for a more constructive international collaboration on a broad range of topics between the US and Europe and the reversal of steel and aluminum tariffs hikes; it may also put the car tariff threat to bed.

- That said, the EU’s push for regulation of big tech, a digital services tax, and a carbon border adjustment mechanism, as well as relatively low defense spending and its protective agriculture policy would likely remain areas of transatlantic tension.

- Finally, we expect the EU to be willing to cooperate more with the US on how to deal with China, albeit in a less aggressive way than the US. This means that a Trump victory would put more pressure on the EU stance regarding China than a Biden win.

With the US presidential elections coming up, this raises the question of whether the result actually matters for the EU. After all, it is no secret that the transatlantic relationship has worsened over the past few years. Should we expect the relationship to be healed if Biden wins the presidency?

We argue below that the outlook for transatlantic cooperation on a broad range of topics would indeed improve under a Biden presidency, that steel and aluminum tariffs might be reversed and that the threat of new tariff hikes would lessen. That said, some areas of transatlantic tension would likely remain and an overarching trade deal – including zero tariffs and barriers on non-car related industrial goods and lower barriers to services trade, as agreed by Juncker and Trump back in 2018 – seems as unlikely under Biden as under Trump.

With Trump in the White House, we think the US would continue to act unilaterally on many fronts and use the threat of raising (car) tariffs in order to force the EU to comply with multiple US requests. As such, it is likely that tariffs on a (very) small portion of EU-US trade would probably increase, although a hike on car tariffs and a full-fledged transatlantic trade war would still remain a downward risk rather than a given. Should that risk materialize, though, it would have large negative economic consequences.

Below we take a closer look at how the Transatlantic relationship has evolved in recent years and which factors may change under a different US presidency and which factors are expected to be insensitive to the election outcome.

Transatlantic relationship turned sour

Unilateralism trumping multilateralism

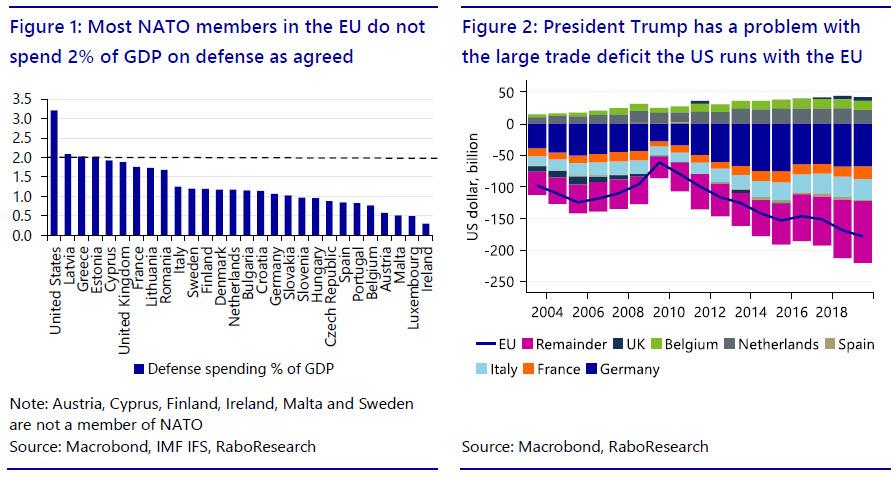

The Trump administration, compared to its predecessors, has chosen for a more unilateral foreign policy approach and has struck an assertive rather than cooperative tone towards the EU. Over the past few years the US has withdrawn from the Paris climate agreement; blocked the appointment of judges for the WTO’s appellate body, effectively paralyzing the international trade body; put in motion its withdrawal from the WHO, to be effective from 6 July 2021. It has also stalled OECD talks on a global tax reform for large multinational companies, including big tech; and has stoked fears the US may reduce support to NATO, over frustration that many non-US members do not pay their fair share, i.e. 2% of GDP.

Steel and aluminum tariffs and car tariff threats

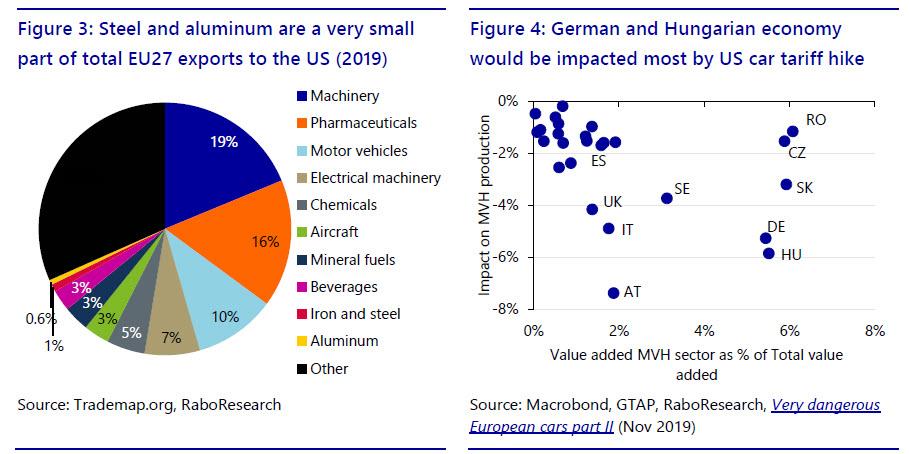

International trade has played a key role in the more assertive tone by the US. By using the threat of import tariff hikes the US has been pushing the EU to increase its defense spending (Figure 1), more actively fight China’s unfair trade practices, ban Huawei from the EU’s 5G network, open up its agriculture market and lower tariffs on US cars (Figure 2).

In response, the EU has tried to accommodate US demands on certain points. For example, several member states have ramped up defense spending and have banned Huawei, whilst the EU has lowered barriers on imports of US beef and lobster. However, the broader picture is that the EU has mainly tried to talk its way out of higher tariffs on its goods, while threatening to retaliate US tariff hikes it deems unjust. So far, the US has indeed hiked steel and aluminum tariffs in 2018, which the EU retaliated, while EU cars have so far been able to dodge that bullet. However, not all ‘tensions’ can be directly related to the more assertive stance by the Trump presidency. One of them is the ongoing dispute between the two biggest aircraft manufacturers in the world.

The Airbus – Boeing dispute

Last year, the US raised tariffs on Airbus jets and on a basket of other EU goods such as wines and cheeses, in total targeting USD 7.5 billion EU products (1.5% of US imports from the EU27+UK). These tariff hikes are the result of a 16-year old dispute between the EU and the US over state subsidies to Airbus and Boeing, respectively. The EU’s trade commissioner Dombrovskis hopes that the US will drop these tariffs, now that the WTO (in October 2020) has authorized the EU to impose tariffs on USD 4 billion of US products to retaliate subsidies to Boeing (1.2% of EU27+UK imports from the US). Yet if the US will not drop those, the EU stands ready to increase tariffs on Boeings and other sensitive US goods, probably over the course of November. Hence, the quality of the relationship between the US and Europe could still play a role in the outcome of this particular dispute.

The EU taking on big tech and climate change

Finally, on tariffs and threats, the Trump administration has indicated that it is not amused by the EU’s plans for a carbon border adjustment tax, tougher regulation on (big) tech and a tax on digital services. The US argue it discriminates against US firms and has warned the EU that it would retaliate any protectionist move in this regard, i.e. any move disproportionally harming US firms. In fact, in response to the unilateral implementation of a digital services tax in France last year, the US published a list of French products it would target with 25% higher import tariffs should France go ahead with its plans to collect the tax. The US has warned others with similar plans, such as Italy and Spain, to be mindful. The EU has responded by threatening to retaliate. So far, France has delayed the collection of the tax and the US has refrained from activating the tariffs, at least until 6 January 2021.

The risk of additional US import tariffs in this respect remains alive, especially since OECD talks to reform the global tax regime seem to be heading nowhere and most EU countries are determined to make tech giants pay taxes where they are earned. The EU is due to present a revised plan for the digital services tax early next year and implement it by January 2023 at the latest. With the agreement on the new EUR750bn crisis recovery fund, the drive to come up with ‘own sources’ of funding has increased. According to the latest known proposal, the EU expects to collect about EUR 1.3 billion annually with the tax, to be used to pay interest and/or redemptions related to the Recovery Fund.

In short, the Transatlantic relationship has been under strain during the last four years under a Trump presidency, whilst the EU is also increasingly working on its own agenda. The US presidential election result could either intensify/accelerate the recent trend or attenuate it, although we believe a full reversal is unlikely, as we explain below.

Biden versus Trump

Backpedaling from unilateralism back to multilateralism?

We expect a renewed Trump administration would continue its America First strategy as described in the previous section, while a Biden win would pave the way for more constructive international collaboration on several topics. For example, a Biden administration would be expected to engage with the EU to, among other things, reform the WTO, by following up this year’s joint statement by the US, the EU and Japan on industrial subsidies and forced technology transfers. In the meantime, it would likely lift the US’ current blockage of judges for the appellate body, supporting the revival of the WTO’s appeal court. Note, though, that while this would soften tensions between the EU and the US, WTO reform will still be very difficult. China would need to approve as well, while formulating a framework on how to adequately detect unfair state aid is far from straight forward. Hence, apart from striving for WTO reform, a Biden administration would likely also look for other ways to team up with the EU to fight China’s unfair trade and investment practices. Given that Biden – like Trump – would adopt a harsh stance against China.

Other areas for improved cooperation would be the fight against climate change – with Biden expected to reaffirm US commitment to the Paris climate agreement – and possibly OECD negotiations on global tax reform. That said, it would remain very difficult for the EU, eager to tax big tech income generated at its soil, and the US, desperate to protect their big tech companies, to find common ground. As long as negotiations are ongoing the EU could chose not to implement a digital services tax on its own, but if negotiations prove to be heading nowhere, the EU may still move ahead unilaterally. Indeed, if no consensus can be found at the EU-27 level, several member states may start collecting the tax on their own.

Finally, Biden is expected to reinvigorate US commitment to NATO, while continuing Trump’s push for higher defense spending in the EU. The latter is a challenging aim, because this belongs to the prerogative of the member states. Furthermore, the COVID-19 crisis has already emptied governments’ pockets and history makes Germany wary of investing extensively in its armed forces. Consequently, we believe, this issue will remain a source of transatlantic tensions.

Tariffs, threats and a new transatlantic trade deal

Turning to trade, the risk of new tariff hikes would likely decline under a Biden administration. A reversal of Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs and, as a consequence, EU retaliatory tariffs seems likely. They currently affect about 1.5% of EU goods exports to the US and 1% of goods travelling from the US to the EU (Figures 3). Furthermore, the threat of car tariffs could be expected to fall by the wayside.

That said, not much progress on an overarching liberalizing trade deal, lowering tariffs on a broad range of (industrial) goods, should be expected. The US currently insists that barriers to agriculture trade will be subject to trade talks as well, yet the EU’s hands are tied (see below). Disagreement seems virtually impossible to overcome. Moreover, plans for an EU digital services tax and a carbon border adjustment mechanism may not go down well with a Biden administration either. Nor would a Biden victory lead to an easy fix for the 16-year old Airbus – Boeing dispute we would argue.

The key difference with a Trump administration, we feel, is that a Biden administration would be more willing to talk with the EU to come up with a negotiated solution on these topics, thus reducing the risk of future tit-for-tat tariff hikes.

If Trump wins he is unlikely to change course. In that case we should expect additional US tariff hikes as the EU, or at least many of its member states, would move forward with a digital services tax. The EU would retaliate. The Airbus-Boeing dispute would arguably also be more difficult to resolve leading to EU tariff hikes related to the Boeing ruling and possibly higher US tariff hikes related to the Airbus ruling. The higher tariffs could have a substantial impact on individual producers, but the total direct macro-economic impact would likely be close to zero. Meanwhile, the threat of car tariff hikes- to push the EU to adhere to different US demands – would remain very much alive, stoking uncertainty. Still, implementation of such car tariffs and a full escalation of the transatlantic trade dispute would continue to be a risk rather than our base case. Should it materialize, the impact would be substantial, though. Especially for economies with large car exports to the US and large car industries, such as Germany, Hungary and Italy. A year ago, we calculated that car production in these countries could shrink by as much as 5%, if the US would hike import tariffs on European cars to 25% (Figure 4).

The EU and its agriculture policy

Common Agricultural Policy has been one of the pillars of the EU. Several Member States have a strong agricultural lobby to protect their domestic farmers and substantially lowering existing import barriers will likely prove to be a bridge too far. At the same time, ideological differences when it comes to genetically modified organisms – generally being approved faster in the US than the EU – will be difficult to overcome. Changes in GMO approval regulations have been made in the past, but they usually are very time consuming and often opposed by both politicians and non-profit groups. So in short, in our view the EU is not likely to make big concessions in this area. This means that a Trump victory would put more pressure on the EU than a Biden win. Trump is likely to take a more aggressive approach on agriculture. Keep in mind that rural areas tend to vote Republican. In a future publication we will dive deeper in the agriculture dossier, also addressing the possible impact of escalation or de-escalation for different F&A subsectors.

The EU and China

With regard to international trade, the European Commission has far-reaching powers, but approving foreign investments in for example 5G networks ultimately falls within the remit of member states themselves. All the European Commission can do (and has done in this respect) is to create awareness and shape guidelines with screening tools for FDI investment and hostile takeovers in strategic sectors and to prevent unfair competition in bids which are due to state aid. Unlike the US, the EU has stopped short of hiking tariffs to force China to open up its markets and alter its policy of state subsidies and forced technology transfers. Instead it is trying to move the country via dialogue on further cooperation and urging for WTO reform. Going forward, while toughening up, the EU is likely to continue to follow the path of dialogue and unlikely to neglect the importance of its economic ties with China.

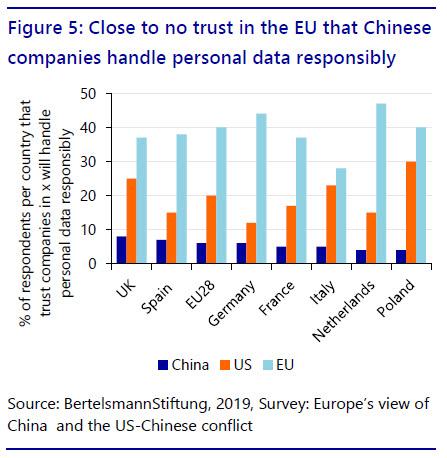

Meanwhile, growing awareness in member states on (security) risks related to especially investment in the 5G networks has led to the exclusion of Huawei in some countries, and heavy debates and altered legislation, lowering Huawei’s chances, in others. From France to Poland and Sweden to Italy. Even Germany, a country with large trade ties with China, is considering legislation effectively preventing Huawei from taking part in its next generation 5G network. Yet an EU-wide outright ban on the Chinese IT company as the Trump presidency has been calling for, appears unlikely. So it remains to be seen whether the EU is being viewed as doing enough in these respects. Moreover, especially Eastern member states, have in fact intensified cooperation with China over the years, by signing up to the one-belt-one-road initiative. Recently Hungary, for example, even welcomed the plan for a R&D center of Huawei in its capital. So while many member states seem to be following more or less the same route, especially when concerning data security risks, some are deliberately following a different path.

All in all, going forward we expect the EU to be willing to cooperate more with the US on how to deal with China, but in a less aggressive way than the US. This means that a second Trump term would put more pressure on the EU stance regarding China than a Biden administration. President Trump is taking a more confrontational approach regarding China than we expect from a President Biden. What’s more, the multilateral approach that Biden has in mind will also lead to smaller repercussions for the EU if it does not fall in line with the US than Trump’s bilateral approach. At the same time, developments in the past years suggest that while the EU is not blind for US threats and pressure, a Biden administration could be more successful in getting the EU on board with its China policy because it would treat the EU as an equal partner, while the Trump administration does not, tarnishing the EU in its honor and forcing it to increasingly work on its own agenda.

In short

We expect a Biden victory to pave the way for more constructive international collaboration on a broad range of topics and the reversal of steel and aluminum tariffs hikes. It may also put the car tariff threat to bed. That said, the EU’s push for regulation on big tech, a digital services tax, and a carbon border adjustment mechanism, as well as relatively low defense spending and its protective agriculture policy would likely remain an area of mutual tension.

A rise in tit-for-tat tariffs on a small group of products would be more likely with Trump in the White House and, we expect Trump to keep the threat of car tariff hikes alive, stoking uncertainty. But the latter’s implementation and a full escalation of the transatlantic trade dispute would continue to be a risk rather than our base case.

Progress on an overarching trade deal, substantially lowering the barriers to trade, seems limited under either president. All in all, while the atmosphere and risks would greatly differ, the direct positive macro-economic impact of an improved transatlantic (trade) relationship under Biden and the negative impact of a strained relationship under Trump seems limited. Clearly, uncertainty and the downward economic risk related to a Trump presidency would be much larger.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/381Enu0 Tyler Durden