Morgan Stanley: We Are Bullish Because Central Banks Will Inject Another $2.8 Trillion Of Liquidity In 2021

Tyler Durden

Sun, 12/13/2020 – 16:48

By Matthew Hornbach, chief rates strategist at Morgan Stanley

Liquidity. It’s What’s For Dinner

With futures contracts tied to the price of water starting to trade last week, this seems a good time to take a look at the impact of liquidity. Liquidity means different things to different people, so before digging in, let me explain what I have in mind. For some, liquidity is the ability to transact a high volume at a low price or bid/offer spread. Others define it as the ease of converting an asset into cash.

The liquidity I’ll discuss here is what greases the wheels of financial transactions and usually emanates from central bank balance sheets. As these balance sheets expand, so does the supply of transactional currency – think of it as electronic money – relative to a given set of investment opportunities. As the supply of this currency increases, financing costs tend to decrease. As a result, the valuation of assets, and usually their prices, change.

How do central banks control the supply of reserves via their balance sheets? They can flood the system by purchasing securities in the open market, i.e., quantitative easing (QE), and drain it by selling them or more commonly letting them roll off without reinvesting. The need for liquidity with which to transact grows with the economy, so monitoring its supply becomes a dynamic process. Keeping tabs on it is also the starting point for an analysis of liquidity’s waterfall effect on broad asset classes.

Quantifying the impact of liquidity from its central bank balance sheet origins down the stream of risk-less and risky assets – the so-called portfolio balance channel – is difficult. Academic research has come to various conclusions, with consensus forming around the following: Central bank asset purchases affect prices of the assets that central banks purchase the most. As a result, opinions vary on the importance of incorporating liquidity into an investment framework.

In the end, tracing the impact of central bank QE on asset prices is like following an ounce of water from one end of a river to the other. It’s practically impossible. Instead, we look for clues that suggest how the cash must be flowing. The leaf that floats downstream leads us to conclude that the ounce of water has flowed along with it. In markets, we first point to the decline of the US dollar (which we thought would result from the liquidity deluge). Then we focus on the unwillingness of government bond yields to rise alongside equities, even though breakeven inflation rates were more than happy to do so.

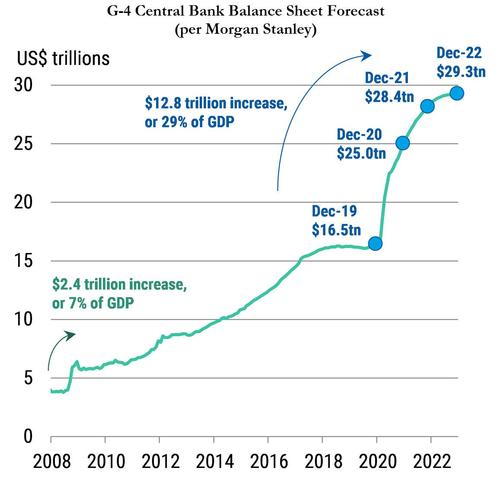

In the absence of absolute proof, seeing is believing. Fixed income investors may remember the negative impact on financing conditions of reducing the reserves held at the Fed in 3Q19. And equity investors may recall how markets reacted in 4Q19 when the Fed reversed course, injecting reserves and improving financing conditions. But who will forget the never-before-witnessed liquidity injection in 2020? Central banks across the G10 will have injected US$4 trillion via government bond purchases alone by year-end.

In the face of that sum, the idea that this tsunami of liquidity hasn’t had far-reaching impacts on asset prices seems outlandish. Naturally, incentives need to align for people to invest available funds. One such incentive in 2020 was the surprisingly strong rebound in economic activity. Another was zero or sub-zero risk-free rates. But the potency of incentives to invest excess cash moderates as the cash piles up. And piling up is an understatement. 2021 is going to be another big year for liquidity injection.

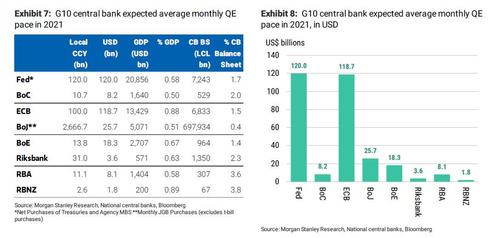

On our projections, G10 central banks will inject another US$2.8 trillion of liquidity next year – just in their government bond purchases. To put this in context, that’s more than twice the amount of liquidity central banks injected in any year prior to the one drawing to a close. Of course, this liquidity doesn’t have to find its way into financial markets immediately. It certainly didn’t this year, as evidenced by the US$4.5 trillion sitting in US money market funds today.

But, if our economists are right and the global economy outperforms expectations, we think the ample liquidity environment will support riskier investments to the detriment of risk-less ones. That means the US dollar has further to fall against a host of G10 and EM currencies next year, and the safest investment of all – US Treasuries – will struggle to make ends meet.

Of course, if central banks signal a reduction in liquidity earlier than we expect, or our economists’ buoyant expectations aren’t met, risky assets could experience a wobble, a theme that might very well feature in our 2021 mid-year outlook.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/37jPyNX Tyler Durden