What Happens To The SLR Next: Here Are The Five Scenarios

Two weeks ago, just before Fed Chair Powell’s final public appearance before tomorrow’s FOMC meeting we addressed the $6.4 trillion elephant in the room: the status of Supplemental Liquidity Ratio, or SLR, and specifically whether or not banks would be granted relief in the form of an extension on this critical leverage ratio when it expires on March 31, one year after the SLR ratio was eliminated to give banks the needed capacity to expand their balance sheets at the peak of the covid crisis so they can soak up the trillions in reserves and excess deposits that the Fed was set to unleash. Unfortunately, even though we explained “Why The SLR Is All That Matters For Markets Right Now“, Powell failed to address this critical topic, with markets assuming that the Fed chair was simply punting it to Wednesday’s Fed meeting.

But perhaps in retrospect this is a lofty assumption because if Powell truly intended to discuss the SLR tomorrow, he would have already leaked a trial balloon or two by now. It’s why in his preview of tomorrow’s main event, Nomura x-asset strategist Charlie McElligott said that “the x-factor for rates or spreads – not to mention stocks – is the Fed’s “deafening silence” on SLR relief—with nothing still yet to be addressed there” leading to the “reflation” bear-steepener getting further pressed by traders until the narrative is altered either by data, some risk-off catalyst or the Fed/politicians finally concede on extending the SLR as the alternative could spark a full-blown bond (and stock) market crash.

And while Powell may again fail to address the SLR tomorrow, the market reaction will be very unhappy as none other than JPMorgan has set up lofty expectations for a Fed discussion having just published a paper titled “Still Waiting on SLR” in which the bank discusses the SLR’s impact on banks, spreads and rates, and lists five potential scenarios that the largest US commercial bank could see playing out, focusing on five potential outcomes.

But first, for those who missed our primer on the issue, some background from JPM.

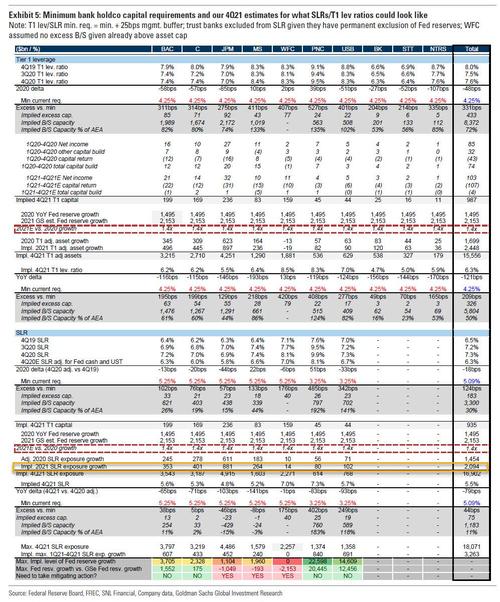

The massive expansion of the Fed’s balance that has occurred implied an equally massive growth in bank reserves held at Federal Reserve banks. The expiration of the regulatory relief would add ~$2.1tn of leverage exposure across the 8 GSIBs. As well, TGA reduction and continued QE could add another ~$2.35tn of deposits to the system during 2021.

While the expiry of the carve-out on March 31 would not have an immediate impact on GSIBs, the continued increase in leverage assets throughout the course of the year would increase long-term debt (LTD) and preferred requirements. Here, JPM bifurcates from Goldman’s assessment: JPMorgan writes that “even the “worst” case issuance scenario as very manageable, with LTD needs of $35bn for TLAC requirements and preferred needs of $15-$20bn to maintain the industry-wide SLR at 5.6%. The constraint is greater at the bank entity, where the capacity to grow leverage exposure to be ~$765bn at 6.2% SLR.” Goldman’s take was more troubling: the bank estimated that under the continued QE regime, there would be a shortfall of some $2 trillion in reserve capacity, mainly in the form of deposits which the banks would be unable to accept as part of ongoing QE (much more in Goldman’s full take of the SLR quandary).

In any case, the regulatory relief granted to large US banks with regards to calculation of Leverage Exposure is scheduled to expire on March 31, and as JPM correctly notes, “the potential impacts on bank balance sheets as well as rates remain front of mind for investors.” Ultimately, JPM reaches the same conclusion as Goldman: the reinclusion of deposits at Federal Reserve banks and Treasuries would increase Leverage Exposure for the 8 GSIBs by ~$2.1tn as of 4Q’20, and keep in mind that balance sheets and deposits held at Federal Reserve banks are expected to grow further in 2021 reflecting TGA reduction and continued QE, to the tune of another $2+ trillion .

Below, JPMorgan provides an overview of what we view as the most likely scenarios regarding regulatory relief.

Scenarios

1. Banks granted short-term extension (<1 year)

Impact on Banks

- Expect some ramping up of LTD and preferred stock issuance at the holding company level as banks look to raise capital for eventual lapse.

Rates

- Swap spreads narrower on disappointment and likely signal of an eventual lapse in carve-outs.

- With SERU1 and SERZ1 at 5.5bp and 6.5bp implied yield respectively, a lapse of existing carve-outs prior to these dates could see these contracts cheapen on anticipated collateral supply.

Front-End Rates

- Resistance to taking on new deposits and shedding of some existing deposits, pushes more liquidity into the banking system; further downward pressures on money market rates.

2. Banks granted long-term extension (>1 year)

Impact on Banks

- Capital and current issuance forecast unchanged. Relief rally in preferreds.

Rates

- Swap spreads widen on anticipation of further bank demand, led by intermediates.

- With SOFR futures already pricing a fairly upbeat outlook over the coming 12 months, limited scope for further richening.

Front-End Rates

- Status quo, continued gradual shedding of deposits over time; less downward pressures on money market rates.

3. Relief ends March 31, banks fully raise capital

Impact on Banks

Expect issuance pace to increase significantly as banks look to get ahead of the leverage constraint. Expect preferred spreads to widen, muted impact on bank spreads.

Rates

- Swap spreads narrower on announcement.

- Swap spreads widen over medium term on commitment to raise capital versus reducing leverage exposures.

Front-End Rates

- Resistance to taking on new deposits, pushes more liquidity into the banking system; further downward pressure on money market rates.

4. Relief ends March 31, banks raise capital & de-lever

Impact on Banks

- Reducing PF leverage assets by $250bn would eliminate banks’ need to issue preferred to remain at 5.6%, but would require ~$25bn of preferred issuance to bring the aggregate SLR to 5.8%.

Rates

- Swap spreads narrower on announcement.

- More sustained narrowing over time on anticipation of bank selling of Treasuries, particularly focused on areas in which bank demand has been strongest, such as intermediates.

- Term repo higher and SOFR futures cheaper on anticipated rise in collateral supply to the market.

Front-End Rates

- Resistance to taking on new deposits and more aggressive shedding of existing deposits, pushes more liquidity into the banking system; further downward pressures on money market rates.

5. Deposit relief extended, relief for Treasuries ends

Impact on Banks

- From an issuance perspective, needs would be moderate if not completely eliminated.

Rates

- Assuming a long-term change and with extension to IDIs and no restrictions on distributions, swap spreads likely widen modestly on perception of less leverage pressure going forward.

- Scoping out of deposits pushes back the need for banks to shed deposits, implying more liquidity stays within banking system.

Front-End Rates

- Scoping out of deposits pushes back the need for banks to shed deposits, implying more liquidity stays within banking system; less downward pressure on money market rates.

* * *

Below are some few more observations from JPM focusing on the underlying economics of the SLR, as well as its impact on banks.

SLR Economics

The Federal Reserve Board’s impending decision on the Supplementary Leverage Ratio, or SLR, had its roots in the Fed’s response to last spring’s COVID-19 economic and financial crisis. (The SLR requires large banks to hold capital against all their assets, regardless of riskiness.) The massive expansion of the Fed’s balance that occurred at that time implied an equally massive growth in bank reserves held at the Fed. This increase in banks’ assets threatened to put pressure on banks’ SLR constraints, which could pressure banks to shed assets or slow loan growth. Added to this, conditions in the Treasury market became very disorderly last spring. In order to allow banks to better intermediate Treasury markets and continue the flow of credit to households and businesses, last April 1st the Board temporarily excluded reserves and US Treasuries from the SLR calculation—an exclusion in effect until the end of this month.

To see the links between the Fed’s actions and bank reserves, Table 1 presents a snapshot of a recent weekly balance sheet of the Federal Reserve System. Its assets are predominantly Treasury securities and agency mortgages. Its largest liabilities are owed to the currency-holding public, the Treasury (through the TGA), and commercial banks (through bank reserves).

Bank reserves are also the “plug” on the Fed’s balance sheet. This means bank reserves can increase in one of two manners: either the asset side of the Fed’s balance sheet increases, or the Fed’s non-reserve liabilities decrease. Most of last year’s $1.6 trillion increase in bank reserves came via the former manner. The huge amount of asset purchases the Fed conducted were financed by the Fed crediting the reserve accounts of the banks of the entities that sold the securities to the Fed.

This source of reserve growth is continuing: the Fed is currently purchasing securities at a $120 billion monthly rate, and Fed officials have indicated that this purchase pace is unlikely to slow anytime soon. Added to this as a source of reserve growth will be a decline in a non-reserve liability, the Treasury General Account, or TGA. One of the Fed’s many roles in the financial system is to be the fiscal agent for the US Treasury, i.e., it’s the Treasury’s bank. To this end, the Treasury maintains an account at the Fed, the TGA. Last year the TGA swelled in size, from $350 billion at the beginning of the year to just over $1.6 trillion by year-end. The Treasury has recently indicated it intends to normalize the size of the TGA, bringing it down to around $500 billion by the end of 2Q21.

As the TGA goes down bank reserves go up. When the Treasury makes a payment, the Fed will debit the TGA and credit the reserve account of the bank of the recipient. In that way a Treasury payment without an offsetting inflow of tax receipts or debt sale proceeds will cause the TGA to go down and bank reserves to go up. When you or I make a payment, bank reserves aren’t similarly affected. The difference is that the Treasury banks directly with the Fed, whereas you and I bank through banks. Our payments will result in the Fed debiting our banks’ reserve accounts and crediting the reserve account of the recipient’s bank: aggregate bank reserves are unchanged. The Treasury, in contrast, is effectively “outside” the banking system. The coming decline in the TGA means that bank reserves will increase by about $1 trillion in coming months, a huge increase that will occur alongside the ongoing addition to reserves due to the Fed’s asset purchases. This increase in reserves further raises the stakes for the Fed’s upcoming decision on the SLR.

Impact on Banks

The re-inclusion of Federal Reserve deposits and Treasuries, as well as continued growth in Federal Reserve deposits over the course of 2021 could drive issuance needs higher for the large banks. On a high level, JPM’s worst case numbers are manageable, and imply holding company issuance basically flat YoY, while preferred needs are slightly higher. The other notable item is YTD issuance – if management teams were concerned about the impact of being leverage constrained, then issuance trends for holding company debt and preferred stock would likely be higher given the receptive market.

Starting with HoldCo long-term debt, the removal of the regulatory relief could impact issuance needs through the TLAC requirement, particularly the leverage exposure based long-term debt requirement. TLAC specifies the minimum required amounts of loss absorbing and recapitalization capacity the 8 GSIBs must hold on an ongoing basis, and requirement must be met by the more constraining of the Risk Weighted Assets (RWAs) or Leverage Exposure requirements. Without regulatory relief, GSIBs constrained by TLAC/LTD requirements as calculated under RWAbased requirements could be constrained by leverage exposure, and banks constrained by leverage-based requirements could see buffers decline/shortfalls increase. The removal of regulatory relief, and JPM’s current $108bn HoldCo issuance, the impacted GSIBs would see their TLAC buffers decline by $34-36bn as compared to buffers over requirements at YE’19.

Turning to preferred stock, Leverage Exposure is the denominator of the SLR, a leverage-based capital requirement for US banks. The US GSIBs face an enhanced SLR requirement of 5.0%, and the numerator of the SLR, Tier 1 Capital, includes preferred stock. If the regulatory relief is not extended, and the denominator of the ratio increases reflecting the re-inclusion of treasuries and deposits at the Federal Reserve, banks could issue preferred stock to shore up SLR buffers. Assuming full removal of regulatory relief, several GSIBS would have SLR ratios below 6.0%. The impacted banks would need $15-20bn of aggregate net preferred issuance to bring their aggregate SLR to 5.6%, $40-45bn to bring the SLR to 5.8%, and $66-$71bn to bring their aggregate SLR to 6.0%. While the optimal buffer for the SLR requirement is hard to pinpoint, it should and will be lower than historical levels.

Here JPM notes that bank-level SLRs are generally closer to the 6% requirement (as compared to 5% for holding companies). Most banks chose not to take the regulatory relief offered to them with regards to deposits at the Federal Reserve and Treasuries at the bank entity that they took at the holding company level. Without regulatory relief for Goldman Sachs and excluding Wells Fargo (as the company remains constrained from growing its balance sheet), the main bank entities of the 8 GSIBs have capacity to increase leverage exposure by ~$980bn (or by ~ $770bn assuming a 20bp buffer over requirements). While equity capital can be down-streamed from holding companies to banks for leverage ratio purposes, this impacts the double leverage ratio. As SLR capacity gets smaller at the bank the HoldCo can downstream equity into the bank, though in this case, they may be limited in the levels of equity they can downstream based on double leverage concerns.

Assuming that banks downstream enough capital to their main bank entities to increase their holding company double leverage ratios to 120%, the GSIBs ex JPM and ex WFC have capacity to increase leverage exposure by ~$2.0tn (or by ~$1.7tn assuming a 20bp buffer over requirements).

Front-End Rates

For the money markets, the decision to not extend SLR relief on reserves and Treasuries could impact this sector in two ways. First and foremost, it could unleash liquidity directly into the money markets. Over the course of last year, reserves have grown by about $1.5tn, most of which were absorbed by large banks as evidenced by the deposit surge on their balance sheets (Figure 6). Currently, large banks hold about 60% (~$10tn) of all deposits in the US banking system. Absent continued relief on reserves, this would put significant pressure on banks’ SLRs such that they would need to raise additional leverage capital and/or decrease their activities. To that end, anecdotally, JPM is already hearing banks trying to find ways to reallocate their deposits or to not accept as many deposits on their balance sheets.

Often, this would result in money shifting out into MMFs or other liquidity alternatives, and intensifying the demand for money market instruments. Given the prospect of further reserves growth this year, either through the drawdown at the TGA or the Fed’s continued QE, the inclusion of reserves back into SLR would likely prompt banks to be more aggressive in shedding deposits off of their balance sheets, all else equal. This would result in more money slushing around front-end, suppressing money market rates.

Second, the inclusion of Treasuries back into SLR could on the margin pressure repo rates higher. In part, this is because bank portfolios are likely going to be less incentivized to purchase Treasuries given the increased regulatory cost to hold these assets, all else equal. To the degree this lessens their demand for Treasuries, this could result in more repo supply until dealers can find other real money buyers to fill the gap. At the same time, bank portfolios that invest their reserves in Treasury repo would likely require a higher spread to IOER to offset the increased regulatory cost. In either instance, this could move repo rates higher on the margin.

* * *

In conclusion, JPM writes that its base case is for the SLR to be extended for both reserves and Treasuries. At a minimum, the extension will take place at the holding company. Relief at the bank subsidiary would be helpful, though given the ability to downstream capital from the holding company to the bank subsidiary and the fact that most banks presumably have not opted into this relief, even in the event regulators decide not to extend the SLR relief at the bank subsidiary, JPM believes that the resulting impact on money markets should be relatively muted (i.e., it does not foresee negative rates in the money markets).

Which is funny, because it was none other than JPM who in its Q4 earnings presentation made it clear that in a world without SLR relief, JPM may be the very first bank to launch negative rates to push back on the coming flood of deposits.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 03/16/2021 – 21:24

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/38PPINc Tyler Durden