As the 2020-21 school year wheezes toward expiration, a foul new public policy term has arisen to meet our fallen moment.

“Experts have coined the term ‘school hesitancy’ to describe the remarkably durable resistance to a return to traditional learning,” The New York Times reported over the weekend. “More than [one-]third of fourth- and eighth-graders, and an even larger group of high school students,” are still learning remote-only, the paper found. “A majority of Black, Hispanic and Asian-American students remain out of school.”

Teachers unions and their apologists are fond of portraying this reluctance as largely an exercise of choice by minority parents who have understandable mistrust of their system’s dedication to safety.

“The real issue now is how are we going to get parents to trust that schools are safe so that they send their kids back to in-person,” American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten tweeted last week.

“NYC schools are open,” New York Times education reporter Eliza Shapiro tweeted inaccurately last week, attempting to fact-check an Andrew Yang campaign advertisement. “The issue [is] that ~600K parents have decided to keep their kids learning from home. Getting those parents back is the actual challenge here.”

As Weingarten and Shapiro know full well (and are reminded of every time they post misleading stuff like this), the decision to keep kids home is not an expressed preference between the binary choices of fully remote and fully in-person instruction. My 7th grader attends school twice a week, and almost never on those days has a live teacher each period. (The kids have been sent outside to “play on their phones” more times than I can remember.) Other middle schoolers and high schoolers, after spending most of the year distance learning, were offered the non-enticing prospect of spending the waning months of a wasted school year going half-time into a classroom where they could all receive instruction by a remote teacher via Zoom.

This unattractive hybrid model is the inevitable result of granting huge swaths of teachers—28 percent in New York City—medical exemptions to work remotely through the end of the school year, regardless of proximity to vaccines. (New York, after having put teachers in front of the line, is now dangling subway passes and entertainment tickets to lure vaccination laggards, and offering shots to nonresidents.)

The more teachers unions exert power over a school district and local political machine, the more that “open” schools equal “Zoom-in-a-room,” the more parents opt out, the more teachers unions attribute the high opt-out numbers to parental preference. It’s a vicious, intelligence-insulting cycle, one that could be significantly broken by fully reopening schools.

“Whether one’s school has reopened,” a detailed American Enterprise Institute study by Vladimir Kogan found last month, “turns out to be the single best predictor of whether parents are willing to send their children back.” Not the rate or trajectory of COVID-19 impact, not the level of historical distrust between communities and schools, but whether local leadership has said unambiguously that it’s safe to come back. “Controlling for local school reopening status greatly attenuates the racial gaps in the observed preferences for online learning,” Kogan wrote.

Conclusion? “Protracted school closures have created a self-reinforcing policy feedback loop, reducing support for resuming in-person learning. Since these closures have been concentrated in large urban school districts, this may have directly contributed to racial disparities in support for reopening schools.”

Educators in slowly reopening districts could react to such findings by hurrying to open doors and spread the good news that schools are among the safest places for people to be. (The seven-day positivity rate among randomly tested New York City schools at the moment is 0.26 percent, or, 1 out of every 380 people.) Instead of that, 14 months after schools first closed, some in leadership positions continue to spread the dangerous fiction that schools are disease-vector deathtraps being pushed to reopen by racists.

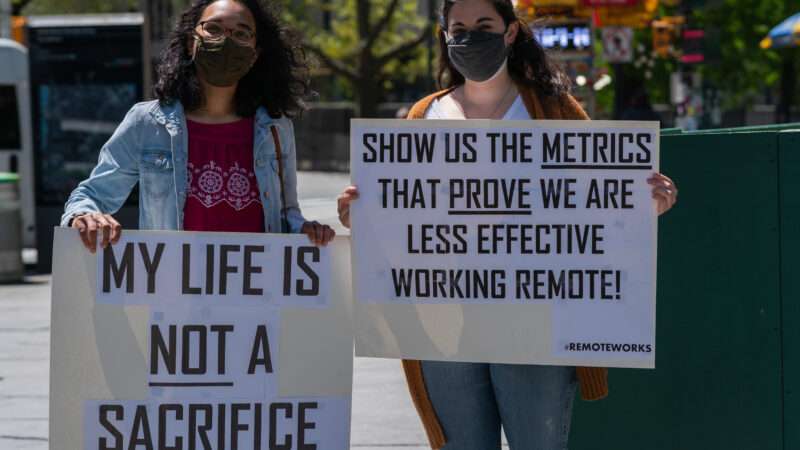

On May 1, the Keep NYC Schools Open coalition held a rally in East Harlem attended by mayoral candidates Andrew Yang and Kathryn Garcia. They were greeted by a counter-protest, featuring teachers wearing sashes that read, “We will not die for DOE” (the latter meaning Department of Education).

It’s bad enough that people who have had access to COVID vaccines for several months, and who ostensibly teach subjects like math and science, would spread the pernicious myth that public school buildings are incubators of death. (The accumulated pandemic body count of kids under 18 is still under 300.)

Worse still, the counter-demonstration was organized in part by neuroscientist Kaliris Salas-Ramirez, who is president of her local Community Education Council (CEC). In New York, CECs are advisory bodies that have real decision-making power at the school district level.

And here is what Salas-Ramirez had to say about the school-opening rally she was protesting: “What we saw at the field on Saturday is white supremacy at its best…. These folks are coming into the neighborhood who are not from the neighborhood; they don’t have to worry about going into the hospital and having ICE come pick them up.”

This kind of poisonous rhetoric, while cuckoo-bananas on its face, is nonetheless routine in reopening debates, and not just in New York. Gee, I wonder what message Harlem public school parents glean from teachers who warn about corpses and education leaders who call reopening racist?

There will come a day when these fights will look like science fiction, even in big Democratic-controlled cities. But that day will probably not come this September. As the school-reopening tracker Burbio put it Sunday:

There are concrete announcements about traditional learning next Fall. There are vague or even what sound like conflicting approaches to virtual learning and no announced plans around the mechanics of delivery. Large percentages of students are opting out of in-person. Learning plans offered across schools vary widely, often with a pronounced demographic or economic skew, and do not closely resemble what a pre-Covid 19 school day would look like. Safety precautions in place in the district appear to exceed the CDC guidelines in an effort to get stakeholders comfortable with the classroom experience. In some cases students are supervised but there are no teachers in the classroom. While there is momentum to bring students into the classroom, all these factors suggest there are considerable obstacles that have not been addressed.

So what will parents do? Increasingly, they will choose non-public options. Hesitancy may have less to do with schooling, and more to do with who is providing it.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3eFwptv

via IFTTT