Netflix is paying President Barack Obama and Michelle Obama millions of dollars to produce shows for them.

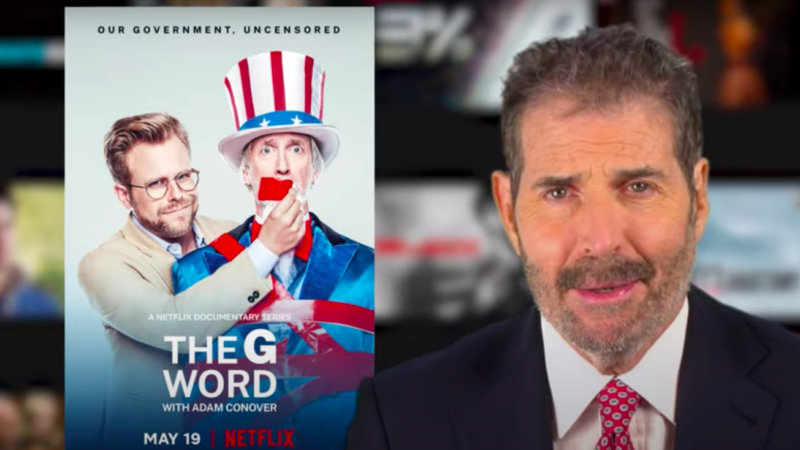

The latest Obama documentary series is The G Word. “G” for government.

As Netflix documentaries go, this one is remarkably stupid. It’s big government propaganda.

Obama begins by claiming that he does his own income taxes, saying, “It’s actually easy.”

I think he’s joking, but it’s not clear.

“I’m amazing at them,” Obama continues hours later. “You can be, too, if you use the helpful tools found at IRS.gov.”

But that’s just silly. It’s so complex that millions of us pay to get help.

Obama’s series is hosted by silly comedian Adam Conover. Conover, correctly, calls himself “an idiot.”

He uses his time with the former president of the United States to make lame jokes and, at one point, to make sandwiches. He compliments Obama on how well he cuts the bread. It’s not funny.

The series occasionally covers some serious issues—meat inspection, for example. But instead of honest reporting, actors do a skit suggesting that, without government, meat companies would sell us dead poisoned rats.

“Food regulation was unbelievably successful,” concludes Conover.

But food is largely safe today mostly because slaughterhouses cleaned themselves up way beyond what government requires. Companies don’t want bad reputations.

One company executive showed me how they voluntarily do extra things like treat beef carcasses “with rinses and a 185-degree steam vacuum.” Also, “equipment is routinely taken completely apart to be swab-tested.”

By contrast, for 90 years, the U.S. Department of Agriculture inspected meat with a crude process called “poke and sniff.” Inspectors stuck spikes into carcasses and smelled them. They kept using the same spikes, so they sometimes spread disease. The government only stopped poke and sniff in the 1990s.

A few times, Obama’s series admits that government agencies mess things up. Conover mocks the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), “not a name you normally hear after the words ‘did a great job.'”

No, but he then claims FEMA fails because it’s underfunded, saying, “How many lives could have been saved if FEMA had had the resources they needed?”

That’s ridiculous. FEMA doesn’t fail because it lacks resources. U.S. disaster relief funds have increased by billions. FEMA fails because it’s a government bureaucracy, and bureaucracies do wasteful things, like bring bottles of water to hurricane victims but then leave them at an airport.

The private sector is more efficient.

The G Word sneers at what it calls “this philosophy that the free market should be trusted over the government.” But Walmart donates supplies much more efficiently than FEMA. They employ sophisticated weather tracking that helps them determine what assets are needed where. They get things to people because they lose money if they don’t.

Obama’s series smears those of us who are skeptical of government handouts.

“In the wake of the civil rights movement,” claims Conover, “some Americans began to resent the fact that the government was now providing assistance to black and brown citizens.”

What? We didn’t resent welfare because we’re racists. We objected because it created a new permanent underclass.

Handouts, President Ronald Reagan explained correctly, “discourage work.”

So Obama’s documentary depicts Reagan as a vicious surgeon cutting valuable government agencies, throwing them into a bucket labeled “free market.”

But government wasn’t cut under Reagan. Federal spending went up during his terms. It always goes up. At one point, the excesses were so grotesque that President Bill Clinton said, “The era of big government is over.”

But it wasn’t. It only grows. Today it’s bigger than ever.

That’s fine, says Conover, because Washington rescued us during the COVID shutdowns with “stimulus checks, small business loans, and corporate tax breaks!”

They don’t mention how much of that money was stolen or that their spending orgy brought 8 percent inflation.

For three hours, Obama and his sidekick say government should do more. Whatever the problem, their answer is always more government and more money.

Maybe someday a president will point out that government has no money of its own and that spending more than you have is a road to ruin.

COPYRIGHT 2022 BY JFS PRODUCTIONS INC.

The post Netflix Teams Up With the Obamas To Produce Big Government Propaganda appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest https://ift.tt/BdSWbFs

via IFTTT