Meanwhile For Bonds, It’s Going From BBBad To Worse

The threat posed by a downgrade of billions (if not trillions) of BBB-rated investment grade bonds, making them “fallen angels” as they slide into “junk bond” territory and resulting in a bond market crisis due to forced selling mandates as the size of the junk bond market soars is hardly new: in fact we covered it for the first time about a year ago in “Hunting Angels: What The World’s Most Bearish Hedge Fund Will Short Next.”

Since then many have hinted that the tipping point for a credit crisis is imminent. Most notably perhaps, last May some of America’s top restructuring bankers, predicted that the day of reckoning is nigh. Take the former head of restructuring at Jefferies and the current co-head of recap and restructuring at Moelis, Bill Derrough, who said at a restructuring event that “I do think we’re all feeling like where we were back in 2007. There was sort of a smell in the air; there were some crazy deals getting done. You just knew it was a matter of time.”

“Even if there is not a recession or credit correction, with the sheer volume of issuance there are going to be defaults that take place,” added Neil Augustine, co-head of the restructuring practice at Greenhill & Co.

And yet, almost a year and a half later, the inevitable BBB downgrade avalanche and explosion in the size of the junk bond market has yet to happen.

Curiously, instead of encouraging complacency, yesterday former Goldman partner and current Dallas Fed president Robert Kaplan issued the starkest warning about surging levels of corporate debt and laid out a scenario where it could suddenly become a big problem for the economy.

“The thing I am worried about is if you get two or three BBB credit downgrades to BB or B, that could lead to a rapid widening in credit spreads, which could then lead to a rapid tightening in financial conditions,” Kaplan said in a Tuesday interview with CNBC’s Steve Liesman.

“We’re got a record level of corporate and to be specific BBB debt has tripled over the last 10 years,” he said on “Squawk Box.” “Leveraged loans as well as BB and B debt have grown dramatically.”

Kaplan’s warning can be summarized by the following charts, the first showing that corporate debt-to-GDP is back to levels which traditionally presage a recession…

… the second showing the tremendous increase in BBB-rated as a percentage of total…

… and finally the fact that despite its BBB rating, 55% of BBB corps should have a junk rating already based on leverage alone.

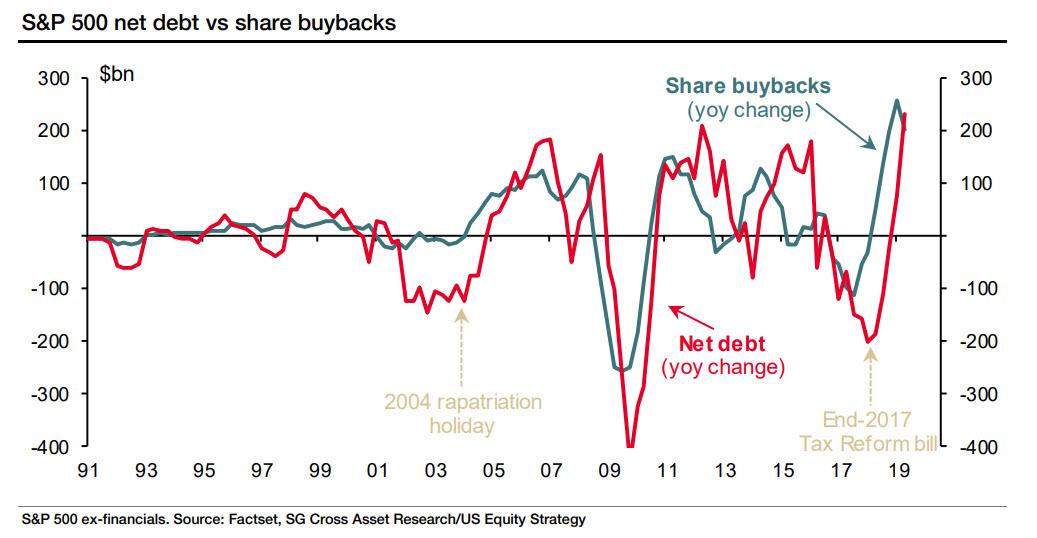

For those unfamiliar, total corporate debt has doubled from $5 trillion in 2007 to $9.5 trillion halfway through 2019. The biggest culprit for this surge: BBB-rated issuance as trillions in debt was sold in the past few years by “investment grade” companies who used the proceeds to buyback their stock.

Yet while we appreciate Kaplan’s warning, it’s finally time the Fed should acknowledge its role in drowning corporate American in debt thanks to its record low interest rates. Investors have pointed to historically low interest rates both as the reason for the high levels of debt and justification for not panicking about its size just yet (throw in the ECB’s monetization of corporate debt and the central bank hypocrisy explodes). The Fed has cut the overnight lending rate three times in 2019, most recently at its October meeting when it reduced the federal funds rate to a range between 1.5% and 1.75%.

The rest of Kaplan’s warning is familiar to most: the sudden drop from the lowest investment grade rating (BBB) to junk will trigger concern over the credit markets and spark a widening in spreads, since a majority of bond managers have hard limits on owning only investment grade bonds and being forced to liquidate junk bonds (the ECB itself suffered through a brief fallen angel scandal in December 2017 when its holdings of Steinhoff bonds crashed following a downgrade to junk).

General Electric has long been eyed as the largest company at risk of triggering such a domino effect, though company officials insist they are doing everything they can to prevent a credit downgrade. More recently, Ford was downgraded to junk and yet this historic event barely registered on the bond market.

“The problem with ’08-’09 was that the lenders were overleveraged. Right now, we have an issue where the borrowers are highly leveraged,” Kaplan added. “My concern is if you have a downturn where we grow more slowly it means that this amount of debt could be an amplifier.”

Yet for every Kaplan issuing a BBB warning, there are at least ten sellside research hacks, desperate to prove to their clients that a slew of BBB downgrades is nothing to worry about (after all, their bond salesmen have to sell their holdings of soon to be CCCrap to someone). Some of the most frequent “justifications” used to explain why there is nothing to worry about are i) these are credit specific worries; ii) BBB rated banks will never be downgraded; iii) if you short the entire space you will be “negative carried” to death before the mass downgrade trigger event happens and iv) the companies are actually deleveraging so it is more likely BBBs will be upgraded rather than downgraded.

The common theme shared by all of the above “considerations” is that they can be effectively ignored as long as the Fed is easing financial conditions, as it is doing now. Of course, once the US finally enters a recession – and the Fed refuses to step in and push up capital markets, delaying the bursting of the bubble any more – none of the above will matter as the downgrade avalanche begins.

Meanwhile, for a surprisingly sober analysis explaining why Kaplan is right and BBBs are indeed the ticking timebomb in the US credit market, we go to the year ahead preview by Goldman’s chief credit strategist Lotfi Karoui, who has been increasingly pessimistic on the US credit market, and writes that going into 2019, he expected the tailwind from strong earnings growth would weaken, thereby leaving the ability and willingness to deleverage as the key drivers of the forward trajectory of credit quality. “This left us erring on the cautious side in terms of balance sheet quality.”

In the end, 2019 ended up surprising even Goldman to the downside. As Exhibit 12 shows, data through the end of the third quarter suggest that net leverage ratios for the median IG and HY non-financial issuer have resumed their upward trajectories, making new highs in HY and approaching the peak reached in the late 1990s in IG. Unlike previous episodes, this re-leveraging has been mostly passive in nature, driven by weak profitability across most sectors.

Meanwhile, as overall corporate leverage approached record levels, for the low end of the IG rating spectrum, one of the side effects of the slowdown in earnings growth has been a delay to the deleveraging plans for most issuers, despite continued commentary emphasizing a focus on gross debt pay down.

And here is a stunning observation: for 48 of the largest non-financial BBB firms – a group which captures over $900 billion of index-eligible debt across the TMT, Healthcare, Food & Beverage and Industrial sectors – the average net debt to EBITDA ratio in the most recent 12-month period (2019) is actually 0.53x higher relative to year-end 2017.

While we acknowledge that there is a fair amount of dispersion in deleveraging progress among relatively smaller issuers, the verdict is still largely lackluster: only two issuers deleveraged by more than 1.0x turn, and only seven reduced leverage by more than 0.50x turn, since year-end 2017. For 2020, earnings growth will likely rebound; our US portfolio strategy team expects S&P 500 EPS growth will reach 6% by year-end 2020. But the forward growth trajectory will be much flatter by post-crisis norms, as profits adjust to a new reality where growth in unit labor costs outpaces price inflation. For credit investors, this will likely mean further delays in the debt reduction plans of over-leveraged companies, particularly for issuers with weak pricing power, and thus more dispersion in returns.

Looking at the chart above, Goldman concludes that “the verdict is still largely lackluster: only two issuers deleveraged by more than 1.0x turn, and only seven reduced leverage by more than 0.50x turn, since year-end 2017.” Meanwhile, Goldman expects that the forward growth trajectory will be much flatter by post-crisis norms, as profits adjust to a new reality where growth in unit labor costs outpaces price inflation. “For credit investors, this will likely mean further delays in the debt reduction plans of over-leveraged companies, particularly for issuers with weak pricing power, and thus more dispersion in returns.”

Said otherwise, since few if any corporations have been punished for incurring ever more debt – most of it being used to fund M&A and/or buybacks – companies have no qualms about issuing even more debt, and explains why almost nobody has deleveraged in the past two years.

Of course, once the longest expansion in history ends and the US economy finally reverses and rating agencies finally wake up and start downgrading companies en masse, that’s when CFOs and treasurers will scramble to do everything they can to reduce their leverage. Alas, it will be too late.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 11/27/2019 – 15:45

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/33s23lb Tyler Durden