When the National Football League drafts its next crop of players this weekend, those draftees will have to be careful about what’s showing on their in-home camera. Don’t drink anything but Pepsi products, don’t snack on anything but Frito-Lay brands, and don’t do any video interviews using Apple AirPods. And definitely don’t try to make a few bucks by hawking a motor oil other than Castrol or a mattress company other than Sleep Number. The league has threatened to keep any player off-camera if an NFL sponsor’s competitor would otherwise be onscreen.

It’s just one of the ways NFL rules keep young players from realizing their true market value, thanks to the league’s take-it-or-leave-it system.

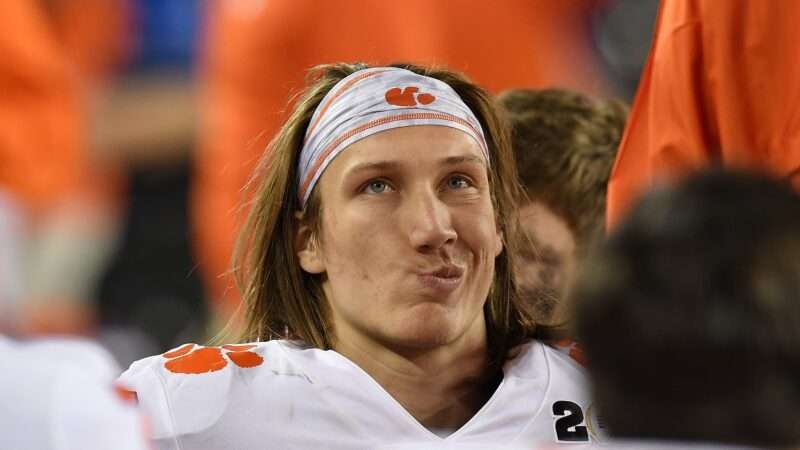

Consider the path of Trevor Lawrence, the Clemson quarterback who’s likely to be the first overall draft pick. In his freshman year, Lawrence led Clemson to an undefeated championship season. If he wasn’t good enough then to enter the NFL draft, he certainly was after his second season, where his team suffered only one loss and Lawrence came seventh in the Heisman Trophy vote.

But Lawrence couldn’t enter the draft until after his third collegiate season, because the NFL won’t allow players to enter the draft until three years after they’ve left high school. Lawrence probably wouldn’t have been the number one pick if he’d entered the draft sooner, but he still would have been earning millions of dollars in the NFL instead of playing for virtually nothing at Clemson, where NCAA rules barred him even from signing endorsement deals. The rule doesn’t just hurt stars like Lawrence: Even an unknown player who just wanted to provide for his family couldn’t try to get a low-salary job playing in the NFL.

In most other sports, players have alternatives to the NCAA, with developmental leagues in the U.S. and the option to play abroad. The NBA, for example, has the G League. Football players could try to make some money in the Canadian Football League before getting signed by an NFL team, but crossover between the sports is rare and CFL salaries are a fraction of the NFL’s. Realistically, NFL draftees are limited to sticking it out for three years in college, a situation the NCAA surely isn’t complaining about.

Even if he was drafted in an earlier year, Lawrence couldn’t have negotiated for a higher salary salary—since 2011, under the collective bargaining agreement between the NFL and the National Football League Players Association, each draft pick has a set salary and a length of four years. (Teams have an option to extend the contracts for first-round picks to five years.) In 2009 and 2010, the first overall draft picks were able to negotiate deals worth more than $70 million over six years. The new structure limited 2011’s number one pick, Cam Newton, to just $22 million over four years.

Barring injury, Lawrence will probably play in the NFL for a long time. But most NFL players aren’t Tom Bradys playing well into their 40s. Their average age of retirement (from football, at least) is 27.6, and 78 percent of players go broke within three years of retirement. The average player’s career lasts just 2.5 years—though for better players who make the opening-day roster in their rookie season, the NFL says their careers average six years.

So under the salary strictures organized by the union and the NFL, a player who doesn’t last more than four years will never have the chance to negotiate for a better salary. What’s more, the contracts are not guaranteed for their whole length, so if a player is cut from the roster after two seasons, he doesn’t get paid the full value of the deal. Running backs have some of the shortest careers in the NFL. Even though they have one of the most important positions, they spend most of their prime years getting paid nothing in college or an amount dictated by the draft pick salary structure.

Draft picks do have some room to negotiate for signing bonuses or performance incentives, but each team has a limit on how much they can spend on rookie contracts. Unlike other players, draft picks don’t have the leverage of a holdout. The salary structure gives them nothing to hold out for, and rules prevent them from renegotiating their contracts if they do hold out.

Of course, the players are doing what they love for a living and making a ton of money while they do it. (The league’s minimum salary is $660,000.) They know the physical risks of getting tackled or tackling others for a living. And the NFL is a private employer that can set its own compensation rules.

But it says a lot about the players union that it organized a deal that can’t keep its former members from going broke after retirement. Players on the union’s Board of Player Representatives are generally not in the early stages of their four-year deal, so there’s little incentive for them to get rid of the salary rules. The older players with most of the union power are making sure they get a bigger piece of the NFL salary pie, the size of which is limited by the league’s salary cap. While the 2020 collective bargaining agreement did adopt some minor changes to this system, the worst parts are set to remain through 2030: the minimum age requirement that keeps able-bodied players from getting paid in the league, the preset salary structure for draftees, and the minimum length of those contracts.

Meanwhile, don’t drink or eat anything other than Pepsi and Frito-Lay products during the draft.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/331aciM

via IFTTT