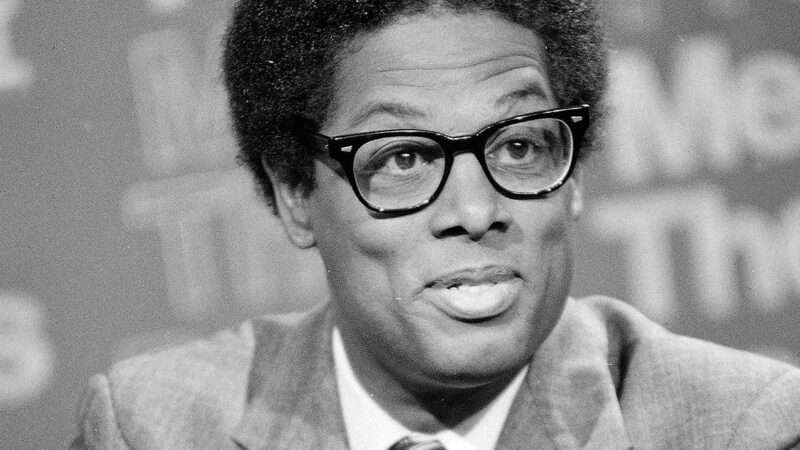

When Thomas Sowell arrived at the University of Chicago in the fall of 1959 to begin his Ph.D. studies, Milton Friedman had been on the faculty for more than a decade. But Sowell hadn’t gone there to study under Friedman, and the University of Chicago hadn’t been his first choice. The original plan was to pursue his doctorate at Columbia University, where he had just earned his master’s degree, and study under another future Nobel economist, George Stigler.

As an undergraduate at Harvard in a course on the history of economic thought, Sowell had read an academic article by Stigler on the theories of the classical economist David Ricardo. Sowell was so taken by the subject matter, and so impressed by Stigler’s command of it, that he turned his own focus toward the history of ideas and resolved to do his graduate work at Columbia under Stigler’s guidance. After Stigler left Columbia in 1958 to join the faculty of the University of Chicago, Sowell followed him there.

Sowell hadn’t been a big fan of the intellectual atmosphere at Columbia or at Harvard, his undergraduate school, and he was looking forward to a change of scenery. At Harvard, “smug assumptions were too often treated as substitutes for evidence or logic,” he recalled. There was a tendency “to assume that certain things were so because we bright, good fellows all agreed that it was so.” Sowell had little patience for such elitism. His classmates seemed to think they “could rise above reasons, and that to me,” Sowell said, “was the difference between pride and arrogance, and between the rational and irrational.” Nor did he ever quite adjust to the social atmosphere in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “I resented attempts by some thoughtless Harvardians to assimilate me, based on the assumption that the supreme honor they could bestow was to allow me to become like them,” he said. “I readily accepted all aspects of what Harvard had to offer that seemed worthwhile, and readily rejected all that struck me as nonsense. The fact that I was avidly reading W.E.B. Du Bois did not keep me from Shakespeare or Beethoven. Indeed, I noticed that Du Bois liked Shakespeare and Beethoven—and had attended Harvard.”

It would be difficult to exaggerate the severity of the learning curve Sowell had faced when he entered college. It’s not just that he hadn’t been a full-time student in almost a decade. He also was unfamiliar with the basics of the academy to a degree that was startling but perhaps not unusual for someone who was the first in his family to reach seventh grade.

Before transferring to Harvard, he had attended night classes at Howard University, a historically black institution in Washington, D.C. “As an example of my academic naivete at this point, when I heard professors referred to as ‘doctor’ I thought they were physicians and marveled at their versatility in mastering both medicine and history or medicine and math,” he later wrote. “It came as a revelation to me that there was education beyond college, and it was some time before I was clear whether an M.A. was beyond a Ph.D. or vice versa. Certainly, I had no plans to get either.”

Sowell’s issues with his fellow undergraduates also may have stemmed to some degree from their age differences. He was 25 when he entered Harvard, had been on his own since leaving home at 17, and had already completed a stint in the Marines. Thus, he was not only older than the typical college freshman but also had significant experience living in the real world. His year at Columbia, a school he described as “a sort of watered-down version of Harvard intellectually,” was only a slight improvement.

By contrast, the University of Chicago was “itself,” he recalled, “and not an imitation of anything.” The Chicago economics department was extremely demanding, and the vetting was brutal, said Ross Emmett, an authority on the history of the Chicago school of economics. “During that period of time, Harvard took in 25–27 students and graduated 25 of them, whereas Chicago took in 70 students and graduated 25 of them.” The department also had a reputation for being conservative, and Sowell’s political views at the time were, in his words, “still strongly left wing and very much under the influence of Marx.” Nevertheless, he had no qualms about leaving Columbia for Chicago: “I was far more impressed by the fact that we shared similar intellectual values.” Graduate economics “is a technical field and not an ideological battleground,” he reasoned. “As I came to understand the Chicago views on economic policy, they seemed less and less like any conservatism that I knew about.”

The interest in Karl Marx had started in Sowell’s late teens, after he purchased a secondhand set of encyclopedias that included an entry on the German philosopher. It’s not hard to contemplate why a black person born during the Great Depression in the Jim Crow South and then raised in urban ghettos might find the precepts of Marxism persuasive. The cruel capitalists, the greedy bourgeoisie, the oppressed masses, the coming revolution that will finally relieve the struggling proletariat from despair—this outlook had a certain appeal to Sowell. “These ideas seemed to explain so much and they explained it in a way to which my grim experience made me very receptive,” he later wrote.

Back then, young Tommy was eking out a living as a messenger for Western Union. “When I left home, I had not finished high school and had a number of these low-level jobs,” he said. “It was a trying time. I had always been in school and so on, and this was starting at the very bottom.”

His job was located in Lower Manhattan, and after work he usually took the subway back up to Harlem, where most of New York City’s black population lived. Occasionally, however, Sowell would ride home atop one of the city’s double-decker buses and marvel at the shifting urban landscape as he headed north. The bus traveled up 5th Avenue, past the upscale department stores that catered to the wealthy. At 57th Street it would turn left, pass by Carnegie Hall, snake around Columbus Circle, proceed up Broadway, and continue north on Riverside Drive through affluent residential neighborhoods. “And then somewhere around 120th Street, it would go across a viaduct and onto 135th Street, where you had the tenements,” he said. “And that’s where I got off. The contrast between that and what I’d been seeing most of the trip really baffled me. And Marx seemed to explain it.” In his 1985 book on Marxism, Sowell wrote that the philosopher “took the overwhelming complexity of the real world and made the parts fall into place, in a way that was intellectually exhilarating.”

Sowell would self-identify as a Marxist throughout his 20s. His senior thesis at Harvard was on Marxian economics, and his master’s thesis at Columbia was on Marxian business cycle theory. Even his first scholarly publication, in the March 1960 issue of American Economic Review, was on the writings of Karl Marx. But like many others who are attracted to Marxist philosophy in their youth, Sowell would abandon it as he became older and more experienced.

It helped that he was never a doctrinaire thinker to begin with and kept an open mind. “I read everything across the political spectrum” in those days, he said. “I understood that there were reasons why people have different views, as I see even today, that it’s not just a question of being on the side of the angels and against the forces of evil.” Even “at the height of my Marxism,” he continued, “I read William F. Buckley and Edmund Burke, because I’d gotten in school, particularly in a ninth-grade science class, the idea of evidence, the importance of evidence and the need to test evidence. That was always there.”

Perhaps that’s what made him such a good fit years later for Chicago, where the importance of thinking empirically wasn’t merely stressed but written in stone. The University of Chicago’s Social Science Research Building, which housed the economics department, had an edited version of Lord Kelvin’s dictum etched over the entrance: “When you cannot measure, your knowledge is meager and unsatisfactory.” The idea was that theorizing is necessary but insufficient. Data and evidence are needed to verify what we think we know.

Sowell had been thinking like a Chicago economist before he ever set foot on campus.

Friedman and Stigler were hardly the only scholars of future renown that Sowell was exposed to in his student days, even if he didn’t always appreciate it at the time. His professors also included Gary Becker and Friedrich Hayek, who would both win Nobels and profoundly impact Sowell’s own scholarship. Becker did pioneering research on the economics of racial bias, and Sowell told me that “anything that dealt with discrimination on my part was within the framework of what Becker had said.” Sowell’s Knowledge and Decisions, which he and other economists count among his best professional work, was inspired by a 1945 academic paper by Hayek on how societies function.

Still, there is a case to be made that no one had a greater impact on Sowell’s career path than Stigler and Friedman. They were his instructors and his mentors. They served on his dissertation committee and even helped him with material needs. When a problem arose with Sowell’s student aid and he contemplated leaving graduate school to find a job, it was Stigler who, without Sowell’s knowledge, secured a generous grant for promising academics from the Earhart Foundation. Sowell later said that grant “enabled me to complete the studies that led to my receiving a Ph.D. at the University of Chicago and to having a career as an economist.” And it was Friedman who, years later, brought Sowell to the attention of Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, where he became a senior fellow in 1980 after he left teaching. Both Friedman and Stigler saw something in Sowell early on that led them to nurture his development as a scholar.

Richard Ware, the longtime head of the Earhart Foundation, recalled receiving the grant request for Sowell. The foundation held Stigler and Friedman in such high regard that the Sowell recommendation was basically rubber-stamped. “When he got nominated, the letter was very short. I don’t know whether Stigler signed it or Friedman or both of them,” said Ware. “They nominated him for the fellowship, and they said he’s a socialist, but he’s too smart to remain one too long. That was the way they put it to the trustees.”

Given that some nine winners of the Nobel Prize in Economics have been Earhart fellows, the foundation obviously had a nose for talent. “Friedman and Stigler say give him a fellowship, we give him a fellowship,” said Ware. “That’s the way we did the program, totally on [that] basis. I think Tom should have a Nobel Prize. I’m not sure he’ll ever get one.”

According to Sowell, he didn’t abandon socialism because he was bamboozled by his Chicago professors. What ultimately began his drift to the political right was a summer job at the U.S. Department of Labor in the summer of 1960: “The job paid more than I had ever made before, enabling me to enjoy a few amenities of life,” he said. “Inadvertently, it also played a role as a turning point in my ideological orientation. After a year at the University of Chicago, including a course from Milton Friedman, I remained as much of a Marxist as I had been before arriving. However, the experience of seeing government at work from the inside and at a professional level started me to rethinking the whole notion of government as a potentially benevolent force in the economy and society. From there on, as I learned more and more from both experience and research, my adherence to the visions and doctrines of the left began to erode rapidly with the passage of time.”

At the Labor Department, Sowell was tasked with analyzing the sugar industry in Puerto Rico, where the U.S. government ran a program that set minimum wages for workers. He noticed that over a certain period, as the minimum wage had been raised, employment had fallen. At the time, he was a supporter of minimum wage laws out of a belief that they helped the poor earn a decent living. But faced with the facts, he started to wonder whether minimum wage laws were pricing people out of jobs.

He also noticed that his coworkers, the department’s permanent staff, didn’t much care either way. “It forced me to realize that government agencies have their own self-interest to look after, regardless of those for whom a program has been set up,” he wrote. “Administration of the minimum wage law was a major part of the Labor Department’s budget and employed a significant fraction of all the people who worked there. Whether or not minimum wages benefited workers may have been my overriding question, but it was clearly not theirs.”

It was this realization, not a lecture at the University of Chicago, that made him “want to re-think the larger question of the role of government in general,” he recalled. “The more other government programs I looked into, over the years, the harder I found it to believe that they were a net benefit to society.”

Sowell came to his free market beliefs by way of reflection and observation. But then, so did Friedman and Stigler, who both spoke of having liberal political inclinations in their student days. Sowell’s readers often express surprise when they discover that he started out as a Marxist, but Sowell said he suspected that at least half his colleagues at the conservative Hoover Institution were also on the left in their 20s.

That’s certainly true of any number of notable black dissident thinkers, from Clarence Thomas and Shelby Steele to Walter Williams, Glenn Loury, and Robert Woodson, who have faced regular attacks from black liberals and other critics often far more interested in questioning their motives than in addressing their arguments.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3whPCHV

via IFTTT