from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2OGBJm4

via IFTTT

another site

Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 35(c) permits “a petition that an appeal be heard initially en banc.” This process allows a court of appeals to bypass the usual three-judge panel, and proceed to hear a case before the entire en banc court. Initial en banc, as it is called, is rare. In recent years, perhaps the most high profile initial en banc came from Richmond. In April 2017, the Fourth Circuit has granted initial en banc to consider President Trump’s travel ban.

The procedure is somewhat controversial, because the full court can hopscotch over the usual three-judge panel–and in turn, leapfrog the three-judge panel assignment. And this procedure must be especially harsh when you are on that three-judge panel. That background brings us to a recent controversy in the Sixth Circuit. (For purposes of full disclosure, I clerked for Judge Danny Boggs from 2011-12).

In October 2020, Senior U.S. District Judge Bernard Friedman declared unconstitutional a Tennessee law that imposed a 48-hour waiting period for abortions. (Judge Friedman, who was appointed to the Eastern District of Michigan, sits in the Middle District of Tennessee as a visiting judge).The Tennessee Attorney General sought a stay of the injunction pending appeal. In February 2021, a divided three-judge panel denied the stay. Judges Moore and White concluded that the law was inconsistent with Casey and Whole Woman’s Health.

Judge Thapar dissented from the denial of the stay. He contended that the 48-hour waiting period was valid under Casey. Judge Thapar wrote that “Given the weighty interests involved in this case, the majority’s failure to issue a stay merits immediate correction either by our court or a higher one.” In other words, the en banc court should jump on the issue as soon as possible. Judge Thapar acknowledged that “the rules are confusing on whether a party may seek en banc review of a stay order.” (I have written about this issue in the 5th Circuit). But, Judge Thapar explained, there are two options: “(1) any active judge may seek sua sponte en banc review, and (2) a party may seek initial hearing en banc on the merits.”

Tennessee chose option #2, and filed a petition for initial hearing en banc. Yesterday, the Sixth Circuit granted that petition.

The court having received a petition for initial hearing en banc, and the petition having been circulated to all active judges of this court, and a majority of judges of this court having favored the suggestion, It is ORDERED that the petition be, and hereby is, GRANTED

Judge Moore dissented from the grant of initial hearing en banc. I don’t think I have ever seen an order like this. I searched for the phrase “dissenting from the grant of initial hearing en banc” and found no other hits. She wrote:

Yet a majority of the Sixth Circuit judges in regular active service have voted to hear this case initially en banc. Because that decision lacks a principled basis and tarnishes this court’s reputation for impartiality and independence, I dissent. . . . By granting that petition, a majority of this court has sent a dubious message about its willingness to invoke that extraordinary—and extraordinarily disfavored—procedure in ideologically charged cases.

Let’s see. Dissenting Sixth Circuit judge charges majority with “tarnishing” the court’s reputation by engaging in en banc antics for an “ideologically charged” case. Stop me if you’ve heard this one before.

Newer readers of this blog may be unfamiliar with the complicated history of the University of Michigan Affirmative Action litigation in the Sixth Circuit. Fortunately, my former boss, Judge Boggs wrote a useful appendix to bring us up to speed. (Judge Boggs actually made his clerks translate the appendix into Latin as part of the interview process; kidding, but you believed it for a moment didn’t you!?). And this history involves both Judge Moore and, however coincidentally, Judge Friedman!

In March 2001, Judge Friedman declared unconstitutional the affirmative action policy at the University of Michigan Law School. And the court granted an injunction to block the University’s policy. The following month, Judge Friedman denied a stay pending appeal. Shortly thereafter, the University of Michigan sought a stay from the Sixth Circuit. And, the University also filed a motion for initial en banc. Even then, such a motion was rare. At the time, Judge Boggs observed, “I have been on the court for 16 years, and I do not recall an initial hearing en banc in my tenure.” I’ll let you read through Judge Boggs’s lengthy, appendix (in English) to learn about how the panel assignments were made. But what’s important for our purposes is that Judge Moore was on the three judge panel that granted the stay pending appeal. And she also voted to grant initial hearing en banc. Her actions directly bypassed a three-judge panel from hearing the matter initially. And the en banc court acted while a Moore-entered stay of district court injunction was in place.

In Grutter, Judge Moore wrote a concurrence in response to Judge Boggs’s procedural appendix. She cited (of all cases) Planned Parenthood v. Casey to charge that his dissent would weaken the Court’s source of “democratic legitimacy.” She added, “Judge Boggs and those joining his opinion have done a grave harm not only to themselves, but to this court and even to the Nation as a whole.”

There is some bitter history on the Sixth Circuit en banc court. By my count, only three active judges from Grutter remain: Moore, Cole, and Clay. Two decades later, the tables have turned.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3tc78eY

via IFTTT

Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 35(c) permits “a petition that an appeal be heard initially en banc.” This process allows a court of appeals to bypass the usual three-judge panel, and proceed to hear a case before the entire en banc court. Initial en banc, as it is called, is rare. In recent years, perhaps the most high profile initial en banc came from Richmond. In April 2017, the Fourth Circuit has granted initial en banc to consider President Trump’s travel ban.

The procedure is somewhat controversial, because the full court can hopscotch over the usual three-judge panel–and in turn, leapfrog the three-judge panel assignment. And this procedure must be especially harsh when you are on that three-judge panel. That background brings us to a recent controversy in the Sixth Circuit. (For purposes of full disclosure, I clerked for Judge Danny Boggs from 2011-12).

In October 2020, Senior U.S. District Judge Bernard Friedman declared unconstitutional a Tennessee law that imposed a 48-hour waiting period for abortions. (Judge Friedman, who was appointed to the Eastern District of Michigan, sits in the Middle District of Tennessee as a visiting judge).The Tennessee Attorney General sought a stay of the injunction pending appeal. In February 2021, a divided three-judge panel denied the stay. Judges Moore and White concluded that the law was inconsistent with Casey and Whole Woman’s Health.

Judge Thapar dissented from the denial of the stay. He contended that the 48-hour waiting period was valid under Casey. Judge Thapar wrote that “Given the weighty interests involved in this case, the majority’s failure to issue a stay merits immediate correction either by our court or a higher one.” In other words, the en banc court should jump on the issue as soon as possible. Judge Thapar acknowledged that “the rules are confusing on whether a party may seek en banc review of a stay order.” (I have written about this issue in the 5th Circuit). But, Judge Thapar explained, there are two options: “(1) any active judge may seek sua sponte en banc review, and (2) a party may seek initial hearing en banc on the merits.”

Tennessee chose option #2, and filed a petition for initial hearing en banc. Yesterday, the Sixth Circuit granted that petition.

The court having received a petition for initial hearing en banc, and the petition having been circulated to all active judges of this court, and a majority of judges of this court having favored the suggestion, It is ORDERED that the petition be, and hereby is, GRANTED

Judge Moore dissented from the grant of initial hearing en banc. I don’t think I have ever seen an order like this. I searched for the phrase “dissenting from the grant of initial hearing en banc” and found no other hits. She wrote:

Yet a majority of the Sixth Circuit judges in regular active service have voted to hear this case initially en banc. Because that decision lacks a principled basis and tarnishes this court’s reputation for impartiality and independence, I dissent. . . . By granting that petition, a majority of this court has sent a dubious message about its willingness to invoke that extraordinary—and extraordinarily disfavored—procedure in ideologically charged cases.

Let’s see. Dissenting Sixth Circuit judge charges majority with “tarnishing” the court’s reputation by engaging in en banc antics for an “ideologically charged” case. Stop me if you’ve heard this one before.

Newer readers of this blog may be unfamiliar with the complicated history of the University of Michigan Affirmative Action litigation in the Sixth Circuit. Fortunately, my former boss, Judge Boggs wrote a useful appendix to bring us up to speed. (Judge Boggs actually made his clerks translate the appendix into Latin as part of the interview process; kidding, but you believed it for a moment didn’t you!?). And this history involves both Judge Moore and, however coincidentally, Judge Friedman!

In March 2001, Judge Friedman declared unconstitutional the affirmative action policy at the University of Michigan Law School. And the court granted an injunction to block the University’s policy. The following month, Judge Friedman denied a stay pending appeal. Shortly thereafter, the University of Michigan sought a stay from the Sixth Circuit. And, the University also filed a motion for initial en banc. Even then, such a motion was rare. At the time, Judge Boggs observed, “I have been on the court for 16 years, and I do not recall an initial hearing en banc in my tenure.” I’ll let you read through Judge Boggs’s lengthy, appendix (in English) to learn about how the panel assignments were made. But what’s important for our purposes is that Judge Moore was on the three judge panel that granted the stay pending appeal. And she also voted to grant initial hearing en banc. Her actions directly bypassed a three-judge panel from hearing the matter initially. And the en banc court acted while a Moore-entered stay of district court injunction was in place.

In Grutter, Judge Moore wrote a concurrence in response to Judge Boggs’s procedural appendix. She cited (of all cases) Planned Parenthood v. Casey to charge that his dissent would weaken the Court’s source of “democratic legitimacy.” She added, “Judge Boggs and those joining his opinion have done a grave harm not only to themselves, but to this court and even to the Nation as a whole.”

There is some bitter history on the Sixth Circuit en banc court. By my count, only three active judges from Grutter remain: Moore, Cole, and Clay. Two decades later, the tables have turned.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3tc78eY

via IFTTT

From Diana v. State, decided yesterday by the Indiana Court of Appeals, in an opinion by Judge Melissa May, joined by Judge James Kirsch and Chief Judge Cale Bradford:

In 2018, Laura Nicoson and three other nurses from Great Lakes Caring, provided in-home care to Diana, who needed nursing care due to a wound on his foot. The in-home care required weekly redressing with bandages, and Nicoson visited Diana’s home in Terre Haute several times to provide such care. Diana’s home was heavily cluttered, and he displayed guns, handcuffs, leg irons, swords, and battle axes throughout his house. Diana also kept boxes of ammunition and knives laying around the house.

On August 10, 2018, Nicoson had an appointment to provide treatment to Diana at his house. Diana was outside of his house when Nicoson arrived, so Diana and Nicoson walked into the house together for Nicoson to treat him. Diana pulled a shofar out of a bucket laying on the hallway floor, and he asked Nicoson if she knew what the item was. Nicoson stated that she did not know what it was, and Diana told her that she “was a sinner and [she] was gonna go to Hell.” He also raised his voice and directed her to read the Bible and attend church. Diana put the shofar back into the bucket, and Diana and Nicoson went into Diana’s bedroom.

Diana grabbed a nearby pocketknife and put it in his pocket, then he sat down on his bed. Nicoson sat on a nearby chair and began treating Diana. Diana then called Nicoson a “goober,” and he asked Nicoson if she knew what he did with “goobers.” Nicoson indicated that she did not know, and Diana said, “I shoot ’em. I have a gun in my pocket.” Diana also indicated that the gun was loaded. Nicoson believed Diana “was very serious and [she] was scared.” Nicoson finished changing Diana’s bandages and left the house.

Diana was convicted of felony intimidation for “communicat[ing] a threat to commit a forcible felony to another person with the intent that the other person be placed in fear of retaliation for a prior lawful act,” as well as for possession of unprescribed methadone. The court upheld the convictions, reasoning in part:

While Diana argues the State did not prove his threat was in retaliation for a prior lawful act, the jury could make such a reasonable inference from Nicoson’s testimony. Nicoson explained that during one of her previous visits to Diana’s house, Diana voiced disapproval of her lifestyle because she lived with a man while unmarried. Diana also criticized Nicoson for not being able to recognize his shofar. Nicoson further testified that Diana called her a “goober” {which he described as a substitute word for “silly person”} before saying he shot “goobers.”

Cohabitating while unmarried, unfamiliarity with religious items, and being silly are all lawful acts. See Ind. Const. Art. 1, § 3 (“No law shall, in any case whatever, control the free exercise and enjoyment of religious opinions, or interfere with the rights of conscience.”). Therefore, we hold the State presented sufficient evidence that Diana threatened Nicoson in retaliation for a prior lawful act.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2RsbFvZ

via IFTTT

From Diana v. State, decided yesterday by the Indiana Court of Appeals, in an opinion by Judge Melissa May, joined by Judge James Kirsch and Chief Judge Cale Bradford:

In 2018, Laura Nicoson and three other nurses from Great Lakes Caring, provided in-home care to Diana, who needed nursing care due to a wound on his foot. The in-home care required weekly redressing with bandages, and Nicoson visited Diana’s home in Terre Haute several times to provide such care. Diana’s home was heavily cluttered, and he displayed guns, handcuffs, leg irons, swords, and battle axes throughout his house. Diana also kept boxes of ammunition and knives laying around the house.

On August 10, 2018, Nicoson had an appointment to provide treatment to Diana at his house. Diana was outside of his house when Nicoson arrived, so Diana and Nicoson walked into the house together for Nicoson to treat him. Diana pulled a shofar out of a bucket laying on the hallway floor, and he asked Nicoson if she knew what the item was. Nicoson stated that she did not know what it was, and Diana told her that she “was a sinner and [she] was gonna go to Hell.” He also raised his voice and directed her to read the Bible and attend church. Diana put the shofar back into the bucket, and Diana and Nicoson went into Diana’s bedroom.

Diana grabbed a nearby pocketknife and put it in his pocket, then he sat down on his bed. Nicoson sat on a nearby chair and began treating Diana. Diana then called Nicoson a “goober,” and he asked Nicoson if she knew what he did with “goobers.” Nicoson indicated that she did not know, and Diana said, “I shoot ’em. I have a gun in my pocket.” Diana also indicated that the gun was loaded. Nicoson believed Diana “was very serious and [she] was scared.” Nicoson finished changing Diana’s bandages and left the house.

Diana was convicted of felony intimidation for “communicat[ing] a threat to commit a forcible felony to another person with the intent that the other person be placed in fear of retaliation for a prior lawful act,” as well as for possession of unprescribed methadone. The court upheld the convictions, reasoning in part:

While Diana argues the State did not prove his threat was in retaliation for a prior lawful act, the jury could make such a reasonable inference from Nicoson’s testimony. Nicoson explained that during one of her previous visits to Diana’s house, Diana voiced disapproval of her lifestyle because she lived with a man while unmarried. Diana also criticized Nicoson for not being able to recognize his shofar. Nicoson further testified that Diana called her a “goober” {which he described as a substitute word for “silly person”} before saying he shot “goobers.”

Cohabitating while unmarried, unfamiliarity with religious items, and being silly are all lawful acts. See Ind. Const. Art. 1, § 3 (“No law shall, in any case whatever, control the free exercise and enjoyment of religious opinions, or interfere with the rights of conscience.”). Therefore, we hold the State presented sufficient evidence that Diana threatened Nicoson in retaliation for a prior lawful act.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2RsbFvZ

via IFTTT

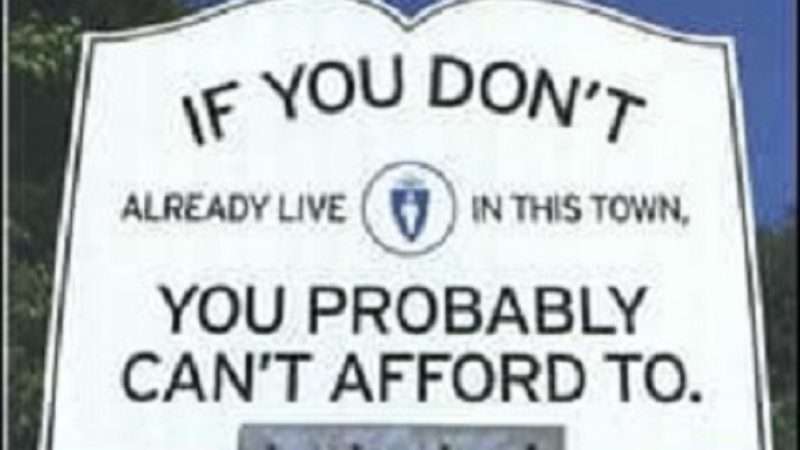

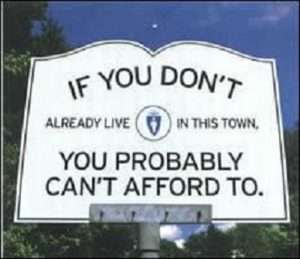

Economists and land-use scholars across the political spectrum have long known that restrictive zoning cuts off millions of people from housing and job opportunities. It is one of the biggest obstacles to increasing economic growth and promoting opportunity for the poor and disadvantaged. But new evidence suggests that the problem is even worse than previously thought.

The work of economists Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti is perhaps the most influential in the literature documenting the impact of zoning on economic growth. Recently, my George Mason University colleague, economist Bryan Caplan, discovered some significant calculation errors in their pathbreaking 2019 article “Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation.” Hsieh and Moretti have graciously acknowledged the mistake.

When scholars err, the effect is often to make their arguments seem stronger or better-supported than is actually the case. In this instance, however, Hsieh and Moretti’s mistake actually made the harmful effects of zoning seem much smaller than is actually the case. Bryan explains:

Where did HM go wrong? On pp.25-6 of their article, they write:

Starting with perfect mobility, the second row in Table 4 shows the effect of changing the housing supply regulation only in New York, San Jose, and San Francisco to that in the median US city. This would increase the growth rate of aggregate output from 0.795 percent to 1.49 percent per year—an 87 percent increase (column 1). The net effect is that US GDP in 2009 would be 8.9 percent higher under this counterfactual, which translates into an additional $8,775 in average wages for all workers.

On the next page, they re-estimate the results with imperfect mobility:

Table 5 shows that changing the housing supply regulation in New York, San Jose, and San Francisco to that in the median US city would increase the growth rate of aggregate output by 36.3 percent (second row). The net effect is that US GDP in 2009 would be 3.7 percent higher under this counterfactual, which translates into an additional $3,685 in average wages for all workers, or an increase of $0.53 trillion in the wage bill.

Both tables indicate that HM are covering the period from 1964-2009. How then can these enormous changes in the annual growth rate, compounded over 45 years, lead to relatively modest changes in total GDP? Answer: They can’t!

The correct estimate to derive from Table 4 is that GDP will be 1.0149^45/1.00795^45=+36% higher, not +8.9%.

Similarly, the correct estimate to derive from Table 5 is that growth will be 1.084% per year (.795%*1.363), so GDP will be 1.0108^45/1.00795=+14% higher, not +3.7%.

Bryan also describes some similar mistakes elsewhere in the article.

The upshot of all of them is that restrictive zoning reduces GDP several times more than Hsieh and Moretti’s original calculations imply. And, I would add that a high percentage of that loss falls on the poor and disadvantaged (who are, for obvious reasons, disproportionately represented among those priced out of desirable housing markets and the jobs available there, as a result of artificial supply constraints imposed by zoning).

I cite some of the earlier Hsieh-Moretti estimates in my own work, including Chapter 2 of my book Free to Move: Foot Voting, Migration, and Political Freedom. I plan to update as as soon as I get the chance!

All of us who work on these issues owe a debt to Bryan Caplan for discovering this problem in the data, and bringing it to our attention. At least in the United States, exclusionary zoning is the biggest property rights issue of our time. It severely constricts the rights of millions of property owners. It is also one of the biggest obstacles to increasing economic growth and alleviating poverty.

Bryan’s discovery shows the latter aspect of the issue is even worse than we thought. He is now working on a book about housing and zoning, which I look forward to with great interest.

In recent years, there has been important progress on reducing zoning in several parts of the country. The Biden administration has included some useful incentives for state and local governments to cut back on zoning in its otherwise mostly awful infrastructure bill. But much, much more needs to be done.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3uGHks0

via IFTTT

Economists and land-use scholars across the political spectrum have long known that restrictive zoning cuts off millions of people from housing and job opportunities. It is one of the biggest obstacles to increasing economic growth and promoting opportunity for the poor and disadvantaged. But new evidence suggests that the problem is even worse than previously thought.

The work of economists Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti is perhaps the most influential in the literature documenting the impact of zoning on economic growth. Recently, my George Mason University colleague, economist Bryan Caplan, discovered some significant calculation errors in their pathbreaking 2019 article “Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation.” Hsieh and Moretti have graciously acknowledged the mistake.

When scholars err, the effect is often to make their arguments seem stronger or better-supported than is actually the case. In this instance, however, Hsieh and Moretti’s mistake actually made the harmful effects of zoning seem much smaller than is actually the case. Bryan explains:

Where did HM go wrong? On pp.25-6 of their article, they write:

Starting with perfect mobility, the second row in Table 4 shows the effect of changing the housing supply regulation only in New York, San Jose, and San Francisco to that in the median US city. This would increase the growth rate of aggregate output from 0.795 percent to 1.49 percent per year—an 87 percent increase (column 1). The net effect is that US GDP in 2009 would be 8.9 percent higher under this counterfactual, which translates into an additional $8,775 in average wages for all workers.

On the next page, they re-estimate the results with imperfect mobility:

Table 5 shows that changing the housing supply regulation in New York, San Jose, and San Francisco to that in the median US city would increase the growth rate of aggregate output by 36.3 percent (second row). The net effect is that US GDP in 2009 would be 3.7 percent higher under this counterfactual, which translates into an additional $3,685 in average wages for all workers, or an increase of $0.53 trillion in the wage bill.

Both tables indicate that HM are covering the period from 1964-2009. How then can these enormous changes in the annual growth rate, compounded over 45 years, lead to relatively modest changes in total GDP? Answer: They can’t!

The correct estimate to derive from Table 4 is that GDP will be 1.0149^45/1.00795^45=+36% higher, not +8.9%.

Similarly, the correct estimate to derive from Table 5 is that growth will be 1.084% per year (.795%*1.363), so GDP will be 1.0108^45/1.00795=+14% higher, not +3.7%.

Bryan also describes some similar mistakes elsewhere in the article.

The upshot of all of them is that restrictive zoning reduces GDP several times more than Hsieh and Moretti’s original calculations imply. And, I would add that a high percentage of that loss falls on the poor and disadvantaged (who are, for obvious reasons, disproportionately represented among those priced out of desirable housing markets and the jobs available there, as a result of artificial supply constraints imposed by zoning).

I cite some of the earlier Hsieh-Moretti estimates in my own work, including Chapter 2 of my book Free to Move: Foot Voting, Migration, and Political Freedom. I plan to update as as soon as I get the chance!

All of us who work on these issues owe a debt to Bryan Caplan for discovering this problem in the data, and bringing it to our attention. At least in the United States, exclusionary zoning is the biggest property rights issue of our time. It severely constricts the rights of millions of property owners. It is also one of the biggest obstacles to increasing economic growth and alleviating poverty.

Bryan’s discovery shows the latter aspect of the issue is even worse than we thought. He is now working on a book about housing and zoning, which I look forward to with great interest.

In recent years, there has been important progress on reducing zoning in several parts of the country. The Biden administration has included some useful incentives for state and local governments to cut back on zoning in its otherwise mostly awful infrastructure bill. But much, much more needs to be done.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3uGHks0

via IFTTT

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis (D) is champing at the bit to ensure his state has one of the nation’s best food laws. Polis has said he’ll sign a bill, Deregulate Meat Sales Direct To Consumers, which will permit farmers and ranchers in the state to sell cuts of meat directly to consumers in the state “without licensure, regulation, or inspection by a public health agency.”

The Colorado bill mimics a key expansion of Wyoming’s groundbreaking food-freedom law. Last year, Wyoming added an animal-share amendment to that law. As I detailed in a column, the animal-share amendment allows consumers in Wyoming to buy individual cuts of meat, such as steaks or roasts, directly from ranchers. This effectively allows farmers and consumers to opt out of a pervasive federal- and state-run meat inspection system that favors large national and international producers over smaller, local ones.

As I explained last year, Wyoming’s law takes advantage of an exemption built into the Federal Meat Inspection Act. While that 1906 law established the processes and parameters for a nationwide scheme of meat inspection, an exemption in the law allows for custom slaughtering of livestock by and for an owner of the animal. Colorado’s law will capitalize on that same exemption.

While North Dakota and a few other states have adopted elements of food freedom legislation, Colorado will be the first state to follow Wyoming’s lead on animal shares. Colorado’s welcome embrace of food freedom should come as no surprise.

In my book Biting the Hands that Feed Us: How Fewer, Smarter Laws Would Make Our Food System More Sustainable and elsewhere, I laud Polis, who was then a member of Congress, for co-sponsoring the PRIME Act, “a bill that would permit farmers to expand options for selling meat locally that’s been processed by local slaughterhouses.”

In 2015, then-Rep. Polis and Rep. Thomas Massie (R-Ky.) held a publicized lunch at which they consumed steak and other animal products that had not been inspected by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

“We think people should be able to go to a farmer’s market, and if a farmer there raised cattle and wants to sell it, they should be able to,” Polis said of the meal. “In a way, it’s restricting capitalism, restricting free enterprise, to say totally legal. You can give [meat] to people, you can share it with people, but the minute there’s money involved, it’s a federal crime.”

That both Polis and Massie continue to live and breathe is evidence that USDA meat inspection is not a necessary precondition for obtaining safe and healthy food. Nevertheless, food safety concerns are front and center for critics of the current Colorado bill.

But, as former Wyoming State Rep. Tyler Lindholm (R)—the chief architect of Wyoming’s first-in-the-nation food freedom legislation—told me in 2017, Chicken Little predictions that Wyoming’s food-freedom law would lead to illnesses or deaths have proven entirely unfounded.

“Wyoming’s local food options have exploded and we still have had 0 foodborne illness outbreaks due to this act passing into law,” Lindholm said. “Currently Wyoming has experienced none of the deaths that we were all warned would happen, and for that matter none of the illness[es] that were prophesied to take place upon passage of the bill.”

Food freedom’s upsides—much unlike its downsides—are very real. In a 2017 column, I listed three key factors that bode well for the spread of Wyoming’s food-freedom legislation: “it expands choices for farmers, home-based entrepreneurs, and consumers; it hasn’t led to negative food-safety outcomes; and it enjoys bipartisan support.”

Polis caught some flak recently for sponsoring a statewide “MeatOut Day.” But that’s merely a distraction. Polis doesn’t want the government to tell you what to eat. Rather, as Polis noted in a great op-ed last month on the importance of food freedom, “one of the values we share is the right to eat whatever we want.“

When it comes to food, that’s the most important value we can share. Hopefully, other states will soon follow Wyoming and Colorado in protecting that essential American right.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/39V6jzN

via IFTTT

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis (D) is champing at the bit to ensure his state has one of the nation’s best food laws. Polis has said he’ll sign a bill, Deregulate Meat Sales Direct To Consumers, which will permit farmers and ranchers in the state to sell cuts of meat directly to consumers in the state “without licensure, regulation, or inspection by a public health agency.”

The Colorado bill mimics a key expansion of Wyoming’s groundbreaking food-freedom law. Last year, Wyoming added an animal-share amendment to that law. As I detailed in a column, the animal-share amendment allows consumers in Wyoming to buy individual cuts of meat, such as steaks or roasts, directly from ranchers. This effectively allows farmers and consumers to opt out of a pervasive federal- and state-run meat inspection system that favors large national and international producers over smaller, local ones.

As I explained last year, Wyoming’s law takes advantage of an exemption built into the Federal Meat Inspection Act. While that 1906 law established the processes and parameters for a nationwide scheme of meat inspection, an exemption in the law allows for custom slaughtering of livestock by and for an owner of the animal. Colorado’s law will capitalize on that same exemption.

While North Dakota and a few other states have adopted elements of food freedom legislation, Colorado will be the first state to follow Wyoming’s lead on animal shares. Colorado’s welcome embrace of food freedom should come as no surprise.

In my book Biting the Hands that Feed Us: How Fewer, Smarter Laws Would Make Our Food System More Sustainable and elsewhere, I laud Polis, who was then a member of Congress, for co-sponsoring the PRIME Act, “a bill that would permit farmers to expand options for selling meat locally that’s been processed by local slaughterhouses.”

In 2015, then-Rep. Polis and Rep. Thomas Massie (R-Ky.) held a publicized lunch at which they consumed steak and other animal products that had not been inspected by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

“We think people should be able to go to a farmer’s market, and if a farmer there raised cattle and wants to sell it, they should be able to,” Polis said of the meal. “In a way, it’s restricting capitalism, restricting free enterprise, to say totally legal. You can give [meat] to people, you can share it with people, but the minute there’s money involved, it’s a federal crime.”

That both Polis and Massie continue to live and breathe is evidence that USDA meat inspection is not a necessary precondition for obtaining safe and healthy food. Nevertheless, food safety concerns are front and center for critics of the current Colorado bill.

But, as former Wyoming State Rep. Tyler Lindholm (R)—the chief architect of Wyoming’s first-in-the-nation food freedom legislation—told me in 2017, Chicken Little predictions that Wyoming’s food-freedom law would lead to illnesses or deaths have proven entirely unfounded.

“Wyoming’s local food options have exploded and we still have had 0 foodborne illness outbreaks due to this act passing into law,” Lindholm said. “Currently Wyoming has experienced none of the deaths that we were all warned would happen, and for that matter none of the illness[es] that were prophesied to take place upon passage of the bill.”

Food freedom’s upsides—much unlike its downsides—are very real. In a 2017 column, I listed three key factors that bode well for the spread of Wyoming’s food-freedom legislation: “it expands choices for farmers, home-based entrepreneurs, and consumers; it hasn’t led to negative food-safety outcomes; and it enjoys bipartisan support.”

Polis caught some flak recently for sponsoring a statewide “MeatOut Day.” But that’s merely a distraction. Polis doesn’t want the government to tell you what to eat. Rather, as Polis noted in a great op-ed last month on the importance of food freedom, “one of the values we share is the right to eat whatever we want.“

When it comes to food, that’s the most important value we can share. Hopefully, other states will soon follow Wyoming and Colorado in protecting that essential American right.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/39V6jzN

via IFTTT